This report is supported by a grant from the Greater Washington Workforce Development Collaborative, a project of the Greater Washington Community Foundation.

The District’s economy is strong on a number of important indicators such as employment, job growth, and increased wages, but the overall trends mask staggering racial inequalities. The District’s deep history of exploitation and discrimination against Black workers—including stolen labor when DC was a hub for slavery, restrictions of free Black workers to the lowest-paid jobs, federal government job discrimination through much of the 20th century, and exclusion of many Black workers from New Deal labor laws—led to present-day racial disparities in many employment-related metrics including occupations, wages, employment levels, benefits, and opportunities to grow wealth.

The differences in employment and income opportunities between Black DC residents and white DC residents are stark. Black residents are seven times as likely as white residents to be unemployed, despite actively looking for work, which cannot be attributed to differences in education or skills-training alone. Similarly, vast racial wealth differences cannot be explained by education, employment, or income alone. Black workers have been excluded from wealth-building opportunities such as homeownership, high-paying jobs and high-value business ownership. This report further finds that:

- There are major disparities in the most common occupations held by Black workers compared with white workers. Black workers are more likely to work jobs that require manual labor and pay lower wages than white workers, such as cashiers, janitors and building cleaners.

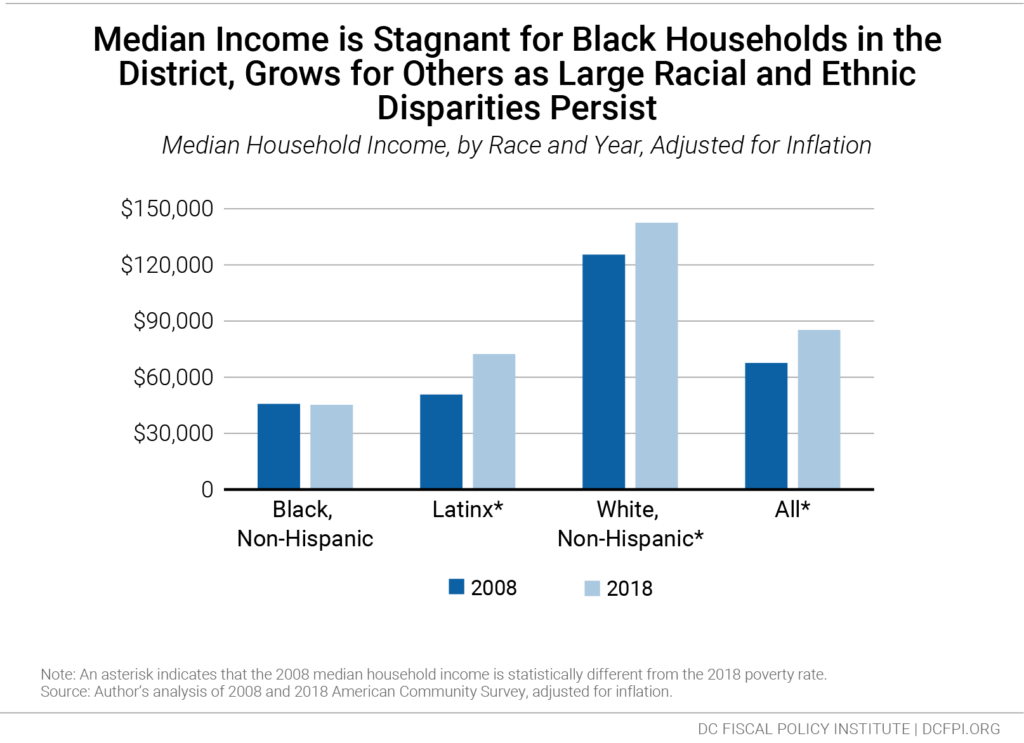

- Black workers’ lack of access to high-paying jobs leads to significant racial income disparities. The Black median household income in DC is $45,200 and has not improved over the past decade, while the median household income for white households is more than three times higher at $142,500 and growing.

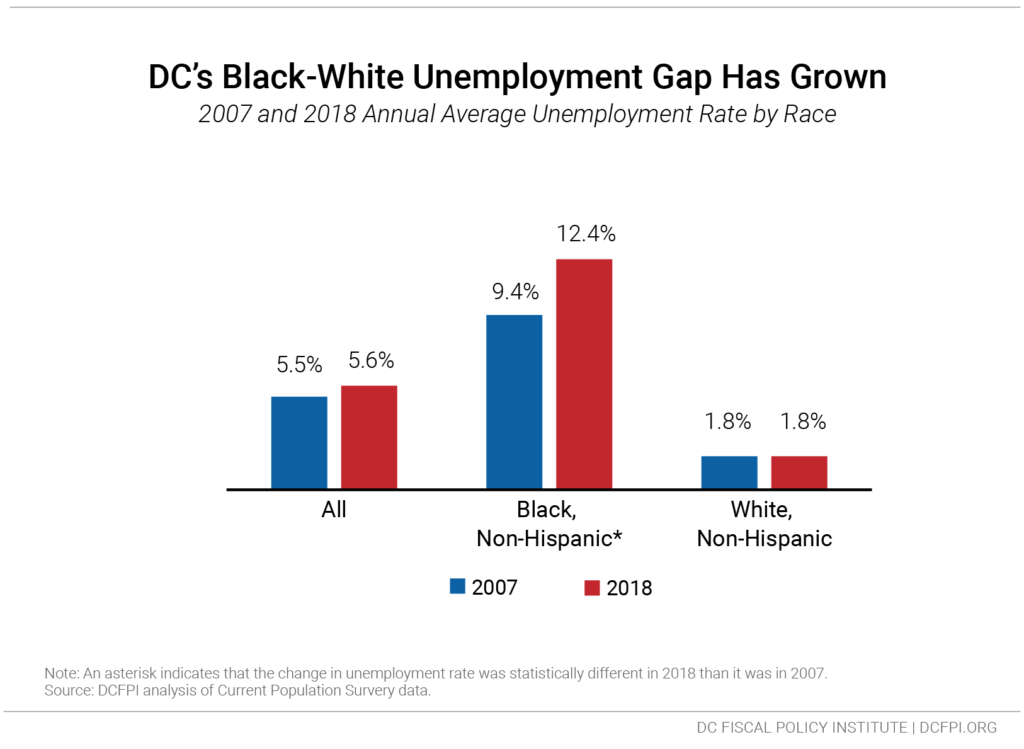

- The District’s Black unemployment levels have failed to fully recover since the recession and Black-white unemployment disparities continue to grow. DC’s returning citizens, who are overwhelmingly Black men, face additional barriers to employment including hiring bias and local regulations that restrict access to occupational licenses.

- Black workers have fewer benefits such as health insurance, paid leave, and employer-provided retirement contributions than white workers. White working parents are far more likely to receive health insurance, as well as a pension or retirement plan, through an employer or un-ion, than Black working parents.

- Black entrepreneurs face greater obstacles to accessing capital than white entrepreneurs which further exacerbates the wealth gap. The average business value (measured in annual revenue) of Black-owned businesses is $125,371, just one-seventh of the average value of white-owned businesses.

Institutional racism is present at every stage of employment from job training and hiring to compensation and promotion, and the District needs far-reaching structural change to instill racial and economic equity. A few District recommendations for putting us on this path include the following:

- Encourage employers to pay a living wage, especially for the lowest paid industries where Black workers are overrepresented.

- Enforce existing wage and worker protection laws and adopt stronger protections.

- Reduce barriers and prioritize employment for returning citizens.

- Eliminate inequitable and ineffective economic development incentives and enforce DC’s “First Source” Law.

- Invest in Black-owned legacy small businesses.

- Strengthen the District’s workforce development systems through increased oversight, improved data collection, adequate funding, and new partnerships with high-demand sectors.

When Black workers succeed, we all succeed. It is time for the District to ensure that we do.

An examination of the District’s long history of exploitation of Black workers and their communities is crucial to understanding current economic racial disparities

Stolen Black Labor

“The District of Columbia (was) the very citadel of slavery, the place most zealously watched and guarded by the slave power and where humane tendencies were most speedily detected and sternly opposed.”

-Frederick Douglass, 1883[2]

The place now known as the District of Columbia was established as a slave capital in 1790 on land seized violently from the Nanticoke and Piscataway peoples[3] by English colonizers. City commissioners immediately needed labor to construct the city so they forced enslaved Black people to labor from sunrise to sunset to clear the physical landscape that would support federal buildings, public squares and the local population. Enslaved Black people further made up about half of the workers used to build the White House and the Capitol.[4],[5] Enslaved Black women primarily were forced into domestic service, taking care of the homes and children of white people.[6]

For a long time, the District was home to a robust slave trade and it became the largest slave-trading city in the nation by the 1830s. But after years of resistance by the enslaved, runaways and free Black and white abolitionists, the District became the first place where enslaved Black people were freed by federal action in 1862.[7] DC was the only instance of direct federal government compensation to enslavers, ultimately spending nearly $1 million, while formerly enslaved people received zero compensation.[8]

Restrictions on Black Labor and Wages and Exclusions from Worker Protections

“You cannot prescribe the same wages for the Black man as for the white man.”

-Democratic Representative Martin Dies, 1937[9]

From DC’s earliest days, free Black people faced overwhelming restrictions on their labor. Prior to emancipation, the District was home to a substantial free Black community that saw the capital as a beacon of freedom and opportunity. But white fear soon led to legal restrictions called Black Codes, which were originally designed to restrict the relative freedom of the free Black community by instituting curfew, prohibiting assembly, and requiring evidence of Black freedom.[10] By 1836, the Black codes included an occupational license ban for any trade with the exception of driving carts and carriages and prohibitions on Black people operating taverns and eating establishments.[11] As a result, free Black men were mostly confined to construction and maintenance work, jobs as hack drivers, and cook and waiter positions while free Black women largely were limited to domestic service positions.[12] By 1900, about 90 percent of Black women workers in the District worked in domestic service.[13]

Black workers were forced to work under harsh and exploitative conditions for the lowest wages. Tipped work spread across the country after the Civil War as a way for white employers to avoid paying formerly enslaved Black people a fair wage—this especially impacted Black Pullman porters and restaurant workers.[14] The positions Black workers were confined to further provided little to no opportunity for wealth building and most of their jobs—most notably domestic service—were excluded from New Deal programs, including the Social Security Act of 1935; the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 which affirmed fair worker unionization practices and collective bargaining; and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 which created minimum wage, the deplorable subminimum wage (which especially affected tipped workers and people with disabilities), the eventual forty-hour work week and overtime provisions.[15], [16], [17]

Many labor unions were fraught with racial discrimination—Black workers were often barred from membership or segregated within unions, and the occupational segregation of Black workers was often reinforced. The Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was founded in 1935 as a direct challenge to the segregated and racist practices of the American Federation of Labor (AFL).[18] And to this day, it remains difficult to unionize domestic work.[19]

Federal and Local Government Discrimination against Black Workers

Many Black DC residents saw public service as a chance to achieve economic mobility, because the hiring process of the federal government was largely meritocratic. By 1891, Black workers made up 10 percent of the federal workforce and it continued to be a major source of employment for Black workers into the early twentieth century.[20] But Black manual workers received little pay and few benefits. Black workers, as a whole, fared worse at the local level, representing just two percent of all District clerks. [21]

The election of openly racist President Woodrow Wilson in 1912 further compounded matters as his administration quickly segregated federal workspaces, restrooms and office buildings, significantly reduced the number of Black federal government appointees and denied qualified Black applicants and Black workers from receiving promotions.[22], [23]

The onset of World War II presented more opportunities for work, and many Black job seekers moved to the District as part of The Great Migration, the exodus of six million Black Americans from the South to the North and West.[24] The Black population in DC increased by nearly 50 percent, totaling more than 280,000 people in the 1940s. But Black workers continued to face employment discrimination for federal and local government jobs. Over 60 percent of Black federal workers were relegated to custodial work while only 2 percent of Black federal workers held higher-level positions.[25]

Black Wealth Deprivation[26]

White policymakers, local administrators and private actors deprived Black people of the many wealth opportunities that white people enjoyed. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) systematically denied Black people from buying homes through redlining.[27] Nationwide, Black people received less than one percent of mortgages between 1930 and 1960, missing out on the opportunity for economic stability and the ability to pass down generational wealth. The GI Bill for World War II veterans similarly excluded Black veterans from receiving low-cost mortgages for homes, tuition assistance, and low-interest business loans.[28]

Black people were also deprived of the communities they created in the only places available to them. Urban renewal was a federal government initiative that largely destroyed Black communities in favor of economic development projects, such as hospitals, offices, universities, housing, highways, etc.[29] In Southwest DC, to support urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s, the city bulldozed 560 acres of land, including 6,000 homes and 1,500 businesses. This displaced 23,000 predominately Black residents, many of whom ended up in Anacostia.[30] This clearance ushered in the construction of Interstate 95 through Southwest DC, which not only was used to encourage and accommodate white flight, but also the movement of jobs outside of the city.[31], [32] In the long run, urban renewal deprived Black people of their homes, communities and stable work.

The Arrival of Home Rule and Mayor Barry Lead to Black Inclusion and Equity

The District regained locally elected self-government—still with Congressional restrictions and oversight—as a result of the DC Home Rule Act of 1973. This presented an opportunity for Black workers to work within DC government and as elected leaders. Black representatives were elected to all but two of the open Mayoral, Chair and Council seats.[33] Under the District’s second mayor, Marion Barry, District government became even more representative of the Black residents it served through an expansion of Black public employment; it improved city services for Black communities such as trash pickup, public transportation, street cleaning and refurbished playground; white contractors were required to hire Black workers to get government business; and Black-owned businesses received a far greater proportion of city contracts.[34]

Other Present-Day Elements of Systemic Racism Create Barriers to Good Jobs and Wealth-Building for Black DC Residents

The employment prospects of Black DC residents also are affected by racial and gender bias and labor market discrimination, higher risk of job loss among Black workers[35], transportation inequities [36], racism in education, and the disparate treatment of Black residents in the criminal justice system.

- Black women historically have been more likely to work than white women and they continue to carry disproportionate financial burdens. They are often the primary financial providers and caregivers of their children, grandchildren and aging parents and face more difficulty finding employment than white women and white men.[37],[38] Black women battle racism and sexism in the labor market, leading to higher rates of unemployment and pay inequities. And once employed, Black women frequently encounter microaggressions and are emotionally burdened with racist tropes. These realities are undoubtedly present within the District.

- Multiple studies in other cities have indicated that Black applicants with identical credentials and educational attainment as white applicants receive far fewer callbacks and job offers.[39], [40] These studies are consistent with the District’s statistics, where the unemployment rate for Black college graduates is three times higher than the rate for non-Black college graduates.[41]

- The US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) “Jobs Proximity Index” data demonstrates that majority-Black neighborhoods in DC, especially in Southeast, have much weaker job markets and access to employment opportunities than more racially diverse neighborhoods.[42] The District Department of Transportation reported that Ward 8 residents have the longest average commutes, making it more difficult to find jobs in accessible locations.[43] In addition to the geographic barriers faced by many Black DC residents, studies have found that employers discriminate against applicants with longer commutes. Given that the average non-white DC resident lives approximately 1 mile further from jobs than the average white DC resident, this discrimination disproportionately hurts Black applicants.[44]

- Racism in education has led to educational differences by race that affect employment. We have shown that in DC, Black students often do not get the resources they deserve, and many leave school without the tools needed to thrive in college or start a good career – upholding generations of racial and socioeconomic disparities.[45] However, even when Black workers have the same educational opportunities and credentials as white workers, disparities persist because of racial bias and discrimination.

- Racial bias in police interactions, arrests, and sentencing leave Black residents disproportionately represented across every part of the District’s criminal justice system. The overwhelming majority of DC returning citizens are Black men.[46] Justice-involved job-seekers face additional barriers to employment such as flawed criminal background checks that limit prospective employee pools and local regulations that restrict access to occupational licenses.[47] These barriers contribute to the low employment rates among employable returning citizens entering supervision, and exacerbate the white-Black employment gap.

Black Resistance

“I think, then, that Negroes must concern themselves with every single means of struggle: legal, illegal, passive, active, violent and non-violent. That they must harass, debate, petition, give money to court struggles, sit-in, lie-down, strike, boycott, sing hymns, pray on steps—and shoot from their windows when the racists come cruising through their communities.”

-Lorraine Hansberry, 1962

Despite occupational and workplace segregation and deprivation of wealth-building opportunities, Black people in the District fought and continue to fight for their rights on all fronts, including the right to be free, work and own a business.

- Mina Queen, one of five hundred enslaved people, filed freedom suits from 1800 to 1862.

- The Pearl Affair of 1848 was the largest escape ever attempted in the nation by enslaved people.

- Black DC residents created self-reliant institutions to successfully counter legal segregation. These institutions included schools, banks, churches, media, benevolent societies, and businesses such as funeral parlors, restaurants, retail stores, and barbershops. The Whitelaw hotel, Industrial Bank, Lee’s Flower Shop, the Miner Normal School, and the first Black YMCA in the country are among those founded.

- Rosebud Murraye, Bertha Saunders and Maggie Keys challenged segregated federal workplaces.

- The New Negro Alliance was established in 1933 by Black private sector workers to advance economic and civil rights. They successfully picketed and boycotted white-owned businesses that refused to hire Black workers, such as Safeway.

These historical themes provide context for the economic inequality that Black workers continue to face in the District.

The Impacts of Anti-Black Racism on Black Workers in the District

The District’s deep history of exploitation and discrimination against Black workers directly led to present-day racial disparities in many employment-related outcomes, including the most common occupations, wages, employment levels, benefits, and opportunities to grow wealth. The barriers that Black residents have faced and continued to face also result in Black residents being denied opportunities to benefit from DC’s current prosperity.

Major Disparities in the Most Common Occupations Held by Black Workers

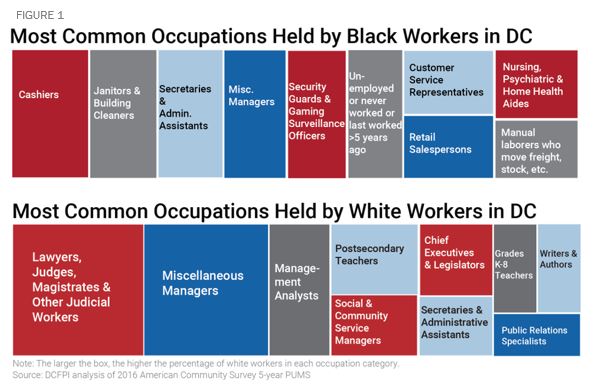

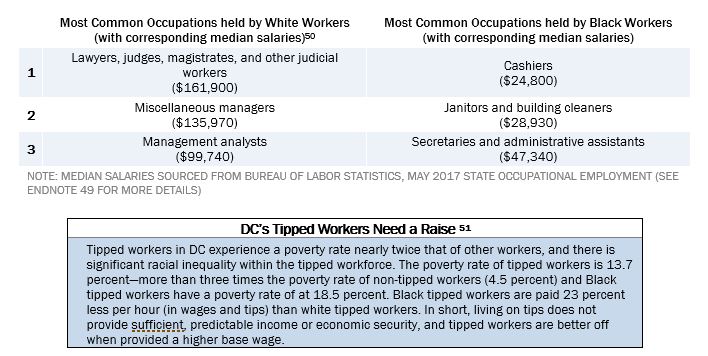

The types of jobs that are more common among Black workers are more likely to require manual labor and pay less compared to the white workers’ most common jobs. The majority of occupations held by Black workers are in the service sector, industries that are plagued by lower wages, temporary contracts, so-called “flexible” schedules that do not guarantee work hours, and fewer benefits (Figure 1).

- The five most common occupations held by Black workers are, in order: cashiers, janitors and building cleaners, secretaries and administrative assistants, miscellaneous managers, and security guards and surveillance officers.

- By contrast, the five most common occupations held by white workers are judicial workers, miscellaneous managers, management analysts, and postsecondary teachers.

- As one sign of racial segregation in jobs, only two occupations are among the top 10 for both Black and white residents: miscellaneous managers and secretaries/administrative assistants.

Black Workers’ Lack of Access to High-Paying Jobs Leads to Significant Racial Income Disparities

The District’s workforce has become increasingly polarized with a growing gap between high-earning white-collar professional workers and low-earning workers who provide essential services, and this gap falls largely along racial lines.

- The median income for white households (non-Hispanic) in DC stood at $142,500 in 2018, over three times as high as the Black median household income at $45,200.

- While the median household income for white households (non-Hispanic) increased by $17,000 from 2008, the median household income for Black households remained flat.[48]

- Income disparities at the ward level are even more alarming. Ward 8, which is 90 percent Black, has a median household income of $34,034, less than half of the District-wide median.[49]

The Black median household income of $45,200 is far lower than the income needed to meet the cost of basic necessities in the District for most households. The DC Council Budget Office estimated that a 1-adult, 1-child family needs to earn $66,113 annually or $31.79 hourly to meet basic needs, without social safety net programs.[52] In comparison, the District’s current minimum wage is $14 per hour, set to increase to $15 per hour in July 2020. A November 2017 assessment by the DC Department of Employment Services (DOES) found that Black residents had the highest percentage of workers making less than $15 per hour, and that the typical minimum wage or low-wage DC worker is likely to be a DC resident (rather than a commuter), female, and less than college-educated.[53]

The biggest racial gaps in mean wages are most evident in the for-profit sector, compared to the public sector and nonprofits. On average, Black workers in the private sector make only 36 percent of what white workers make. In the nonprofit sector, Black workers make 58 percent of what white non-profit workers earn. Generally speaking, more transparent and meritocratic public sector labor practices around hiring and promotions should help minimize job discrimination and wage disparities. The wage gap is smallest in the public sector, it is still substantial; on average, Black workers make 66 percent of white federal government workers.[54]

Employment Levels for Black DC Residents Have Not Fully Recovered Since the Recession & Disparities Continue to Grow

While the Great Recession hurt all households across the nation, it was particularly disastrous for Black Americans due to the structural and systemic forces outlined above. Overall unemployment levels in the District have steadily recovered from the recession to 5.3 percent in November 2019 (the latest data available), but the recovery has been largely uneven across racial groups.[55] Unemployment among Black residents remains higher than in 2007, despite nearly a decade of economic growth.

- 12.4 percent of working-age Black DC residents were unemployed in 2018, on average, compared with 9.4 percent in 2007 prior to the Great Recession.[56]

- At the same time, employment levels fully recovered for white workers and as a result, the white-Black employment gap is far higher now than in 2007.[57]

Racial Inequities in Education Limit the Ability of Black DC Residents to Succeed in DC’s Economy

Racial differences in educational attainment alone do not explain differences in occupations. However, racism in our education system and differences in educational attainment exacerbate existing disparities in access to higher-paying jobs. Institutional racism in DC’s education system is marked by inequitable funding, which shortchanges students who attend schools in low-income, primarily Black neighborhoods. From FY 2019 to FY 2020, 80 percent of the schools that faced deep budget cuts (of five percent or more) were in Wards 7 and 8.[58] This has cascading negative consequences on teacher retention, access to high-quality curriculum materials and advanced courses, extracurricular opportunities, and mental health supports. The lack of strong, targeted public investments inhibits the educational attainment of low-income students and Black students who may be at risk of falling behind.

As the District’s labor market increasingly favors more educational attainment, this limits opportunities for residents with less than a Bachelor’s degree and disproportionately hurts Black DC residents because 27 percent of Black residents have a four-year degree compared to 91 percent of white DC residents.[59] Black workers in the District with less educational attainment are also forced to compete for jobs with an influx of college-educated workers from neighboring states; for example, 30 percent of administrative workers in DC have college-degrees, positions that generally should not require this level of education, a rate that is much larger than the national average.[60] The DC Department of Employment Services (DOES) estimated that in 2020, 72 percent of all jobs in the District will require at least some postsecondary education.[61] DOES also estimates that the fastest-growing occupational categories are: 1) professional and business services and 2) educational and health services, both of which have formal training and educational requirements.[62]

Black workers with college degrees also struggle to find jobs that match their skills. National statistics demonstrate that recent Black college graduates are more likely to work in jobs that typically do not require a college degree than recent white college graduates – a form of “underemployment.”[63]

Inequities in Job Quality and Benefits

Black workers have fewer benefits—such as health insurance, paid leave, and employer-provided retirement contributions—than white workers.

Health Insurance

Equitable health coverage is important in the District, where there are significant disparities in health outcomes across racial groups.[64] Access to health coverage is associated with a range of benefits including timely preventive care services, better management of chronic health issues, and better health outcomes.[65]

The District has the second-lowest uninsured rate in the nation due to DC’s adoption of key components of the Affordable Care Act, which helped provide more health coverage options for residents of all incomes. However, uninsured rates vary greatly by race, with Black residents in DC twice as likely as white residents to lack coverage.[66] Moreover, less than half (38 percent) of Black working parents in the District get insurance through an employer- or union-provided health insurance plan, compared to 57 percent of white (non-Hispanic) working parents.[67]

Retirement Plans

Social Security, employer-provided pensions, and personal savings are crucial for building financial security later in life, but approximately 44 percent of the District’s private-sector employees do not offer retirement plans.[68] This is especially significant for Black residents in the District, who represent a higher share of DC’s older adults than any other racial group.[69] As of 2015, over half of all Black workers are not covered by a workplace retirement plan compared to less than a third (32.5 percent) of white workers. Nearly 70 percent of workers earning below $25,000 annually are not covered – disproportionately impacting Black residents.[70] The District’s increasingly high cost of living paired with a lack of financial resources in old age could force many older Black residents to work beyond traditional retirement age.

Paid Leave

Access to paid leave also varies dramatically along racial lines. The Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) only guarantees unpaid leave, which many families cannot afford to take. In the District, similar percentages of white (non-Hispanic) working parents and Black parents are eligible for FMLA at 59 percent and 55 percent, respectively. However, nearly 60 percent of white (non-Hispanic) working parents are both eligible and can afford to take it compared to about a third of Black working parents.[71] The percentage of Black working mothers who are eligible and can afford to take it is even lower, which is troubling given that 88 percent of DC’s Black mothers are key family breadwinners compared to only 49 percent of white mothers.[72]

The District has taken steps to remedy these inequities by passing the Universal Paid Leave Act (UPLA) in December 2016.[73] UPLA is an important step forward, but the overly prescriptive proposed rules may exclude tens of thousands of workers from accessing the benefits.[74]

Black Entrepreneurs Face Greater Obstacles than White Entrepreneurs in Accessing Capital, Exacerbating the Wealth Gap

Racial wealth disparities in the District are even starker than income disparities, as the median net worth of a white household is 81 times greater than the median net worth of a Black family.[75] Wealth accrual is vital to economic security and mobility, but Black residents are often excluded from wealth-building opportunities such as homeownership, high-paying jobs, and high-value business ownership.

Throughout the nation, Black-owned firms have a more difficult time obtaining credit and receiving loans than white-owned firms, even after accounting for business performance and credit risk.[76] Barriers to capital make it more difficult for Black business owners to grow their businesses. As a result, there are jarring disparities in the average business value, measured in annual revenue, of white-owned and Black-owned businesses in the District.

- The average value of white-owned businesses is $817,438 in annual revenue, 6.5 times higher than the $125,317 average value of Black-owned businesses.[77]

- Small businesses east of the Anacostia River are lent less money than small businesses in the western parts of DC. For example, Wards 7 and 8 received $3,407 and $3,709 in small-business loans per employee, respectively, compared to $6,006 per employee in Ward 3 and $6,536 in Ward 4.[78]

Recommendations for Building Racial Equity in Employment and Entrepreneurship in DC

There are no simple or quick steps to reverse the impacts of centuries of racism on the jobs and income opportunities for Black DC residents. Nevertheless, there are a series of steps the District can take, focused on Black workers earning low wages and Black entrepreneurs, that will help the District move toward greater economic equity.

Encourage employers to pay a living wage, especially for the lowest paid industries where Black workers are overrepresented

Given that the minimum wage still falls short of meeting the basic needs of DC workers, the District should continue to take steps to encourage the employers to pay a “living wage” to their workers. A living wage is a more accurate depiction of the cost of a household’s basic needs. A Massachusetts Institute of Technology analysis shows that a worker with two children in the District must make $33.60 per hour to support their family, while an individual with no dependents must make $17.76 per hour.

In the District, a living wage would particularly benefit workers in food preparation and service, healthcare support, personal care and service, building and grounds cleaning and maintenance, and sales and related occupations that typically pay below the living wage standard.[79]

There are at least two ways to expand access to living wage jobs in DC.

- Update DC’s Official Living Wage: The District requires government contractors and recipients of government assistance to pay their workers at least DC’s living wage standard. Yet that standard—set in the mid-2000s and only adjusted for inflation since then—is just $14.50 per hour. That is only fifty cents more than the current DC minimum wage and well below the MIT living wage standard even for a single person.[80] By 2020, the official DC living wage will actually be lower than the minimum wage, meaning that it will have little or no impact on raising worker wages. Revisiting the DC living wage level will raise wages for many workers who work under DC contracts.

- Implement the Living Wage Certification Program: The District is developing a Living Wage Certification Program to recognize and incentivize small businesses who pay a living wage and reward them with business promotion. As the District works to develop this program, it should use an updated living wage level, not DC’s current $14.50 per hour living wage. The certification process also should account for businesses that offer a good benefits package and determine whether program design could negatively impact Black-owned legacy businesses (see below). It should prioritize finding living wage solutions for the lowest-paid industries to ensure that workers who overwhelmingly take care of our needs, are also able to take care of their own.

Enforce existing wage and worker protection laws and adopt stronger protections

Despite the existence of labor laws such as the Minimum Wage Act of 2013, Paid and Sick Leave Amendment Act of 2013, Workplace Fraud Amendment Act of 2013 and the Wage Theft Prevention Amendment Act of 2014, wage theft violations by employers—instances where employers don’t comply with wage or other labor laws—remains prevalent and disproportionately impact low-wage Black workers. For example, a recent report commissioned by the Office of the Attorney General (OAG) found that illegal worker misclassification, a form of payroll fraud, results in labor cost evasion ranging from 16 to 48 percent within the District’s construction industry.[81] And a 2016 paid sick day compliance project conducted by DC Jobs with Justice found that 75 percent of businesses visited were violating the law by denying and failing to inform workers about their rights to paid sick days.[82]

The District should work to ensure that it responds to worker complaints in a timely manner. Current legislation states that an initial determination be given within 60 days of the complaint, but many workers often wait beyond the 60-day period. A timely response is urgent as it is often difficult for lower-wage workers to issue a complaint because they can face retaliation from their employer which can take even longer to resolve, resulting in a further loss of pay and sick leave. A 2017 report by the DC Just Pay Coalition recommends that the District adopt a policy to respond to employer retaliation attempts within 48 hours and shorten the complaint timeline to resolve all complaints within 60 days.[83]

The report further recommends that the District create an Office of the Worker Advocate that could operate similarly to the Office of the Tenant Advocate.[84] This office should be an independent agency that provides worker-friendly access to labor rights, and technical advice and legal services to workers engaged in disputes with their employer. This office should advocate on an ongoing basis for legislative changes to improve worker protections in the District.

Reduce barriers and prioritize employment for returning citizens

The overwhelming majority of returning citizens to the District are Black men, many of whom were unjustly targeted by punitive laws around illegal drugs, over-policing and sentencing disparities. Given that recently returned Black job applicants face the highest barriers to employment due to racial bias in the hiring process, the District should reduce the barriers that returning citizens face such as flawed criminal background checks and difficulties obtaining professional and occupational licenses.

Criminal records, which include both convictions and non-convictions, continue to have devastating impacts on employment opportunities. The Urban Institute found that roughly one in seven District residents has a publicly available criminal record from the past 10 years, only half of whom were convicted of a crime.[86] Ninety-six percent of people sentenced in DC and impacted by these collateral consequences are Black. And while the District’s Fair Criminal Record Screening Act of 2014, aka “Ban the Box,” prohibits many District employers from inquiring about criminal records prior to a conditional offer of employment, it remains difficult to enforce and punitive action can still be taken for offenses as minimal as an arrest without a conviction.[87]

Fortunately, several councilmembers introduced bills in recent years to accelerate record-sealing and increase the number of felonies that are eligible. The District should ensure that the final legislation allows for automatic expungement (i.e. not just sealing) of all misdemeanors and minor felonies after completion of a sentence.

Occupational licensing requirements are often burdensome and restrictive. Over 70 occupations in the District require a professional license, including barber and cosmetology licenses which many returning citizens seek to obtain. Many licenses require onerous training, education, fee requirements and licensing boards consider criminal background information as a part of the licensing process, which can prevent returning citizens from acquiring these jobs.[88] The Community Justice Project at Georgetown University Law Center and the Council for Court Excellence recommend a number of ways licensing in the District can be reformed including:

- a pre-licensing for petition process for people with criminal records;

- prohibiting boards from considering non-conviction background information and older convictions; and

- tailoring the standard boards use to review convictions by focusing only on whether it affects the applicant’s ability to perform the duties related to the license and applying that new standard across all licensed professions.[89]

The Council should adopt the Removing Barriers to Occupational Licensing for Returning Citizens Amendment Act of 2019 which would establish a uniform standard for occupational licensing boards to only consider pending accusations or prior convictions that are directly related to the occupation, among other things.[90]

Use the creation of a newly regulated cannabis industry to focus on equity

The District will eventually consider legislation to legalize, tax and regulate the sale of recreational cannabis. Because this will create a brand-new industry, with both job and ownership policies, this gives the District the chance to ensure that Black residents share in the benefits. This is especially important given that Black residents faced the most negative criminal justice impacts of prior cannabis policies. Policymakers should apply a restorative approach that addresses how criminalization caused historic harm to the Black community. The new industry should be designed to ensure equitable access to the industry in employment, entrepreneurship and consumption – particularly for people who have cannabis-related arrests and convictions.[91] This could include, for example, setting aside a share of licenses for businesses in cannabis cultivation and sale for under-represented communities, and business loans and technical assistance for aspiring business owners.

Eliminate inequitable and ineffective economic development incentives and enforce DC’s “First Source” Law

In 2017, the District spent more than $61 million on economic development subsidies and other forms of government financial assistance to businesses.[92] This is slightly more than DC spent on local funding for the District of Columbia Public Library that same year. However, research about tax subsidies demonstrates that they often have few local benefits and are ineffective in changing businesses’ behavior. In other words, they do very little to help bring jobs to DC’s longtime Black residents. There also is very little transparency or oversight for these programs.[93]

DC’s First Source Program has been in effect for over thirty years to help reduce unemployment. The law requires companies with contractual agreements with the District government totaling $300,000 or more to enter into a First Source Employment Agreement with the DC Department of Employment Services. Fifty-one percent of all new hires on any government-assisted project or contract between $300,000 and $5 million must be District residents. For projects totaling over $5 million, the requirements for hiring DC residents are more specific.[94] Almost a decade ago, the DC Auditor found that contracts with companies agreeing to First Source hiring requirements of DC residents and paying Living Wage requirements were poorly monitored and non-compliant. [95] Only a quarter of the projects investigated met the First Source hiring goals and the Living Wage requirements were entirely ignored.[96]

Few changes have been adopted since then to address these problems. In September 2019, the DC Council introduced a bill that would require the Department of Employment Services (DOES) to publicly provide notice about active First Source projects, modify reporting requirements to be project-specific, and require that any special hiring agreements between DOES and First Source contractors are developed prior to the start of a project and shared online.[97] The First Source Program could be an effective strategy for providing job opportunities and reducing unemployment. But without reporting standards and the risk of penalties for noncompliance, the District will never be able to enforce First Source requirements and other strategies to employ DC residents.[98]

More broadly, the District should:

- Fully disclose all incentive deals including how much assistance was promised to the company, the number and quality of jobs promised, and timely updates about how much job creation occurred in comparison to their requirements.

- Narrow the scope of businesses that are eligible for economic development subsidies by geographic location, business size, and other metrics.

- Create a recapture provision stating that when a company fails to uphold its agreed upon job creation and quality standards, the city may recapture some or all of the awarded economic development subsidy.

If the District replaced often-wasteful corporate subsidies with spending to directly support longtime residents and locally-owned businesses, Black workers would be more likely to benefit from the city’s thriving economy.

Invest in Black-owned businesses

Instead of wasting the District’s resources on ineffective tax subsidies, the District should directly invest in Black-owned legacy small businesses—businesses that have supported their communities for years but are at risk of displacement due to soaring rents and property tax assessments. The DC Council took steps in the right direction by introducing the Protecting Local Area Commercial Enterprises Amendment Act and the Longtime Resident Business Preservation Amendment Act, both of which create programs targeting long-term support for legacy businesses. As the bills move forward, they could be better targeted to mitigate commercial displacement of Black-owned legacy small businesses and forge a more equitable commercial landscape.

For example, the Protecting Local Area Commercial Enterprises Amendment Act could include provisions to specifically target support to legacy businesses that are most at risk due to gentrification. This could include requiring businesses to show that rising rent is causing an economic hardship and targeting tax abatements on businesses in areas where commercial values have risen sharply (based on analysis by the DC Chief Financial Officer). Without such targeting, the bill could cover a very large number of businesses across the city, including many that are financially healthy, and could be very costly.[99]

The District should also ensure that local Black-owned businesses are awarded an equitable portion of city government contracts. In 2019, a group of Black entrepreneurs organized to request that the DC government study disparities in contracting dollars awarded to Black-, minority-, and women-owned businesses.[100] Establishing a new task force to study the disparities and better target awardees of the certified business enterprise program could help bring new contracting opportunities for DC’s Black-owned businesses and allow them to expand.

Strengthen the District’s workforce development systems through increased oversight, improved data collection, adequate funding, and new partnerships with high-demand sectors

The District should strengthen its existing workforce development programs to better connect residents with long-term career opportunities. DC operates a diverse set of employment and training programs that include vocational programs in public schools, apprenticeship programs, and on-the-job training.

However, there are many indications that these investments are not living up to their potential. In recent years, for example, the Department of Employment Services (DOES) spent less than its available funding, despite widespread need for jobs services. While this problem has lessened in the last year, new concerns have surfaced that certain funds dedicated to adult job training were used for alternative purposes.[101] In May 2019, several participants in DOES-funded programs testified about mismanagement in the training programs and the lack of permanent job opportunities afterwards.[102]

Increased oversight and reporting standards for DOES programs could help ensure that funds are used effectively and that participants find long-term employment. Improving data collection is essential for increasing oversight and reporting standards. The District must improve its capacity to generate and collect data to track workers’ progress along educational and career pathways. Better data could also help workforce development programs make mid-course corrections if workers are not being adequately served by their current programs.

Further, the District should continue to build sector partnerships to bring together training providers, academic institutions, unions, employers, and DC government, among others. Last year, Mayor Bowser launched the DC Infrastructure Academy (DCIA) as a joint effort between the city and others including Pepco, Washington Gas, D.C. Water, and the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Similar partnerships could be explored in other fast-growing industries not currently covered by DCIA such as healthcare and hospitality.

[1] The authors would like to thank Brittany Alston for developing the original outline for this report.

[2] Angela Y. Davis. Women, Race & Class. Vintage Books, 1981, pg. 103.

[3] The authors choose to use the preferred naming of the National Museum of the American Indian as identified in “We Have a Story to Tell: Native Peoples of the Chesapeake Region,” 2006.

[4] Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (The University of North Carolina Press, 2017), pg. 2-3, 17, 31, 39, 48-49.

[5] Damani Davis, Slavery and Emancipation in the Nation’s Capital: Using Federal Records to Explore the Lives of African American Ancestors, Prologue Magazine, Spring 2010, Vol. 42, No.1.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Doni Crawford, DCFPI Remembers DC Emancipation Day, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 16, 2019.

[8] Asch and Musgrove, 114-118.

[9] Ira Katznelson. Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time, W. W. Norton & Company, 2013, 582.

[10] Asch and Musgrove, 2, 44-45.

[11] Kijakazi, Kilolo, Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins, Mark Paul, Anne E. Price, Darrick Hamilton, and William A. Darity Jr. 2016. The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital. Durham, NC: Duke University; Washington, DC: Urban Institute; New York: The New School; Oakland, CA: Insight Center for Community Economic Development, pg.8-9.

[12] Ibid.

Asch and Musgrove, 59.

[13] Ibid. 208.

[14] Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, The Racist History of Tipping, Politico, July 17, 2019.

[15] Ira Katznelson. When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America, W.W. Norton & Company, 2005, pg. 53-61.

[16] Huixian Li, Fact Sheet: The Tipped Minimum Wage & Working People of Color, The Leadership Conference Education Fund and Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, April 2018.

[17] Alexia Fernández Campbell, A loophole in federal law allows companies to pay disabled workers $1 an hour, Vox, May 3, 2018.

[18] Asch and Musgrove, 263-266.

[19] Angela Y. Davis, 95-98.

[20] Asch and Musgrove, 170-171, 218.

[21] Ibid, 207-208.

[22] Ibid, 225.

[23] Douglas A. Blackmon. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II, Anchor Books, 2008, pg. 357-358.

[24] Isabel Wilkerson. The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration, Vintage Books, 2010, pg. 8-11.

[25] Asch and Musgrove, 273-274.

[26] Ibram X. Kendi, The Greatest White Privilege Is Life Itself, The Atlantic, October 24, 2019.

[27] Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chuck Collins, Josh Hoxie and Emanuel Nieves. The Road to Zero Wealth: How the Racial Wealth Divide is Hollowing Out America’s Middle Class, Prosperity Now and Institute for Policy Studies, September 2017, pg. 15.

[28] Ibid, pg. 16.

[29] Richard Rothstein. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2017, pg. 127.

[30] Kilolo Kijakazi, et. al, 25.

[31] Ibid. 25-26.

[32] Bradley L. Hardy, Trevon D. Logan and Johan Parman. “The Historical Role of Race and Policy for Regional Inequality,” Place-Based Policies for Shared Economic Growth, by Jay C. Shambaugh and Ryan Nunn, The Hamilton Project, Brookings, 2018, pg. 52.

[33] Asch and Musgrove, 379-381.

[34] Ibid, 394-395, 399.

[35] Tomaz Cajner, Tyler Radler, David Ratner, and Ivan Vidangos, Racial Gaps in Labor Market Outcomes in the Last Four Decades and over the Business Cycle. Federal Reserve Board, 2017.

[36] Gavrielle Jacobovitz, Geographic Unemployment Disparities in DC: An Economic Renaissance Parted by a River, East of the River News, September 2018.

[37] Nina Banks, Black women’s labor market history reveals deep-seated race and gender discrimination, Economic Policy Institute, February 19, 2019.

[38] Christian E. Weller, African Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good Jobs, Center for American Progress, December 5, 2019.

[39] German Lopez, Study: anti-black hiring discrimination is as prevalent today as it was in 1989, Vox, September 2017.

[40] Andy Kroll, The persistent black-white employment gap, Salon, July 2011.

[41] Linnea Lassiter, Still Looking for Work: Unemployment in DC Highlights Racial Inequity, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 2017.

[42] DC Department of Housing and Community Development, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and the Poverty and Race Research Action Council (PRRAC), Draft for Public Comment: Analysis of Impediments to Fair Housing Choice, September 2019.

[43] Faiz Siddiqui, Armand Emamdjomeh and John Muyskens, When commuting in the DC region, distance doesn’t tell the whole story, Washington Post, April 2017.

[44] David C. Phillips, Do Low-Wage Employers Discriminate Against Applicants with Long Commutes? Evidence from a Correspondence Experiment, University of Notre Dame, July 2018.

[45] Qubilah Huddleston, Raising the Bar: Budgeting for a Strong Public Education System, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, December 2019.

[46] Owen Bement, Shea Diaz, and Franziska Schroder, From Prisons to Professions: Increasing Access to Occupational and Professional Licenses for DC’s Returning Citizens, The Community Justice Project at Georgetown University Law Center and Council for Court Excellence, 2017.

[47] Marina Duane, Emily Reimal, and Mathew Lynch, Criminal Background Checks and Access to Jobs: A Case Study of Washington DC, Urban Institute, July 2017.

[48] Tazra Mitchell, The District’s Rising Economic Tide Isn’t Lifting Black Boats, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 2019.

[49] U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Retrieved from Census Reporter Profile page for Ward 8, DC, 2018.

[50] Cheryl Cort and Patrick McAnaney, Making Workforce Housing Work: Understanding the Housing Needs of D.C.’s Changing Workforce, Coalition for Smarter Growth, March 2019.

[51] Brittany Alston, Repeal Is Not The Answer. DC Tipped Workers Need A Raise, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 2018.

[52] Susanna Groves & John MacNeil with Anne Phelps & Joseph Wolfe, Economic and Policy Impact Statement: Approaches and Strategies for Providing a Minimum Income in the District of Columbia, Office of the Budget Director of the Council of the District of Columbia, February 2018.

[53] Mason Miller, Paula Mian, and Ye Zhang, Minimum Wage Impact Study, IMPAQ International, LLC submitted to District of Columbia Government Department of Employment Services, November 2017.

[54] DCFPI analysis of 2017 American Community Survey 5-year PUMS.

[55]Bureau of Labor Statistics, State Employment and Unemployment — November 2019, U.S. Department of Labor, December 20, 2019.

[56] DCFPI analysis of Current Population Survey data.

[57] DCFPI analysis of Current Population Survey data.

[58] Alyssa Noth, Educational Equity Requires An Adequate School Budget, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, December 2019.

[59] Prosperity Now Scorecard, District of Columbia: Outcome, 2019.

[60] Maurice Jackson (Ed.), An Analysis: African American Employment, Population & Housing Trends in Washington, DC., Georgetown University, submitted to the DC Commission on African American Affairs, 2017.

[61] Ibid, 9.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Jhacova Williams and Valerie Wilson, Black workers endure persistent racial disparities in employment outcomes, Economic Policy Institute, August 2019.

[64] District of Columbia Department of Health, Health Equity Summary Report: District of Columbia 2018, 2018.

[65] Carolyn Y. Johnson, What we know about how health insurance affects health, Washington Post, September 2015.

[66] Prosperity Now Scorecard, District of Columbia: Outcome. 2019.

[67] Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy, Heller School for Social Policy & Management, Brandeis University, Working Parents Who Are Policyholders of Employer-Provided Paid Health Insurance (Share) by Race/Ethnicity, Waltham, MA: 2014.

[68] David John and Gary Koenig, Fact Sheet: District of Columbia, Workplace Retirement Plans Will Help Workers Build Economic Security, AARP Public Policy Institute, August 2015.

[69] Ellen Squires, A portrait of DC’s older adults, DC Policy Center, June 2018.

[70] David John and Gary Koenig, Fact Sheet: District of Columbia, Workplace Retirement Plans Will Help Workers Build Economic Security, AARP Public Policy Institute, August 2015.

[71] Joshi, P., Geronimo, K., Romano, B., Earle, A., & Acevedo-Garcia, D.. Family and Medical Leave Act policy equity assessment, Waltham, MA, Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy, Heller School for Social Policy & Management, Brandeis University, 2015.

[72] National Partnership for Women & Families, Paid Leave Means A Stronger D.C., January 2019.

A key family breadwinner is defined as, “a single mother who heads a household or a married mother who contributes 40 percent or more of the couple’s joint earnings.”

[73] D.C. Law 21-264. Universal Paid Leave Amendment Act of 2016.

[74] Ed Lazere, Testimony at the Public Oversight Roundtable on Implementation of the Universal Paid Leave Amendment Act of 2016, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 2019.

[75] Kilolo Kijakazi, et. al, vii.

[76] Lindsay Li, Report Demonstrates Gaps in Access to Capital for Minority-Owned Small Business, Opportunity Finance Network, November 2017.

[77] Prosperity Now Scorecard, Data by Issue: Businesses & Jobs, Business Value by Race, 2019.

[78] Urban Institute, Closing Equity Gaps in DC’s Wards and Neighborhoods, 2018 (updated 2019).

[79] Tazra Mitchell, Living Wages Help Build the Economy, Hill Rag, October 29, 2019.

[80] Government of the District of Columbia, Living Wage Act Fact Sheet, Department of Employment Services, December 12, 2018.

[81] Office of the Attorney General, Illegal Worker Misclassification: Payroll Fraud in the District’s Construction Industry, September 2019, pg. 1-2.

[82] DC Just Pay Coalition, Making Our Laws Real: Protecting Workers through Strategic Enforcement of DC’s Labor Laws, 2017, pg. 3.

[83] Ibid. pg. 8

[84] Ibid. pg. 10-11.

[85] American University School of Public Affairs, Key Studies and Data About How Legal Aid Reduces Barriers to Employment, April 2019.

[86] Joshua Kaplan, In D.C., Sealing Your Criminal Record Can Be Harder Than Almost Anywhere Else, Washington City Paper, November 2019.

[87] Ibid.

[88] The Community Justice Project at Georgetown University Law Center and the Council for Court Excellence, From Prisons to Professions: Increasing Access to Occupational and Professional Licenses for D.C.’s Returning Citizens, pg. 7-10.

[89] Ibid, 6 – 17.

[90] DC Council Bill B23-0440, Removing Barriers to Occupational Licensing for Returning Citizens Amendment Act of 2019, 23rd Council (2019).

[91] Doni Crawford, Testimony of Doni Crawford on the Prohibition of Marijuana Testing Act and Medical Marijuana Program Patient Employment Protection Amendment Act, October 9, 2019.

[92] Good Jobs First, Subsidy Tracker, Washington DC, 2017.

[93] For example, DC’s Qualified High Technology Company (QHTC) program provides generous tax cuts to companies that self-identify as “high tech,” based on a very loose definition, to attract these companies to DC. But many program recipients were in DC before the tax subsidies were created, meaning there wasn’t actually any “incentive” or new jobs for existing DC residents.[ii] Another recent example is the Line Hotel’s $46 million tax break in exchange for hiring a certain number of DC residents and meeting other conditions. An audit found that the Line Hotel did not uphold the conditions for the tax break, but the District had little legal recourse to easily revoke the abatement in its entirety.

[94] Department of Employment Services, First Source Program.

[95] Lawrence Perry, Testimony before the Council of the District of Columbia Committee on Labor and Workforce Development. Public Roundtable on the District of Columbia’s First Source Hiring Law, Office of the DC Auditor, June 2018.

[96] Good Jobs First, Accountable USA – District of Columbia.

[97] DC Council Bill 23-0436, First Source Community Accountability Amendment Act of 2019, 23rd Council (2019).

[98] Organizing Neighborhood Equity DC (ONE DC), and the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University, “Trained to Death” and Still Jobless: A Case Study of the Efficacy of DC’s First Source Law, Economic Development Policies, and the Marriott Marquis Jobs Training Program, June 2015.

[99] Tazra Mitchell, Testimony of Tazra Mitchell At the Public Hearing on the Protecting Local Area Commercial Enterprises Amendment Act of 2019 and the Longtime Resident Business Preservation Amendment Act of 2019, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, November 6, 2019.

[100] James Wright, Task Force Questions Racial Disparity in City Contracts, The Washington Informer, June 2019.

[101] Mitch Ryals, Is the Department of Employment Services Properly Using Adult Job Training Services?, Washington City Paper, October 2019.

[102] Mitch Ryals, Participants in a Disastrous D.C. Workforce Development Program Still Lack Employment, Washington City Paper, May 2019.