This report was developed with grant support from The Policy Academies.

A person’s early working years are a critical time to acquire workplace skills, connections, and experiences that can help lay the groundwork for a successful career. Yet persistent systemic racial inequities in DC’s labor market disrupt young Black workers’ ability to make ends meet and thrive long-term. An estimated 4,100 District youth ages 16 to 24 were unemployed, on average from 2021 to 2023, of which about 71 percent were Black. The Black-white youth unemployment gap over the same period was nearly 5-to-1.[1] Chronic unemployment or disconnection from the workforce leave many young Black workers struggling to generate a work history, build skills and professional connections, and make ends meet.

These racial disparities are the result of historic and ongoing racism, exploitation, and discrimination in the labor market, which systematically marginalizes and excludes young Black and non-Black workers of color from employment and economic opportunity. They also reflect the fact that young Black residents disproportionately face barriers to employment including poverty, homelessness, community-level violence, the foster care system, failing schools, and the carceral system, because of systemic racism.

Unemployment harms young workers in immediate and longer-term ways. The DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) partnered with the local non-profit DC Action to lead focus groups of District youth who faced employment barriers, and they shared that when unemployed, they experienced housing instability, resorted to unsafe work, or struggled with depression and suicidal ideation. Over the longer term, workers from economically disadvantaged backgrounds who are unemployed in their 20s later on end up in jobs with low wages, few benefits, or too few hours. Young workers in the DC Action focus groups want a different future and expressed that they:

- Want to be business owners, doctors, attorneys, among other “white collar” careers, but need a range of supports and services aimed at mitigating barriers and helping them achieve their goals.

- Experience deep harm from involuntary unemployment and need supports to avoid cycles of disconnection from work.

- Want jobs that align with their interests, skills, and goals, and would benefit from working with employers who are equipped to support youth.

- Are interested in employment programming that offers well-paid, year-round work experience that supports their career trajectory, and feel that existing public workforce programs fail to do so.

A DC youth job guarantee can cut through structural barriers erected by a long history of racism and inoculate against persistent labor market bias and discrimination with the certainty of employment, a livable wage, and benefits. A job guarantee paired with robust supports can also help address the failures of the District’s school system to achieve racially equitable outcomes or its workforce programs in addressing chronic racial disparities in employment. And, a job guarantee can offer young workers year-round opportunities and supports lacking in DC’s current public workforce programs. In doing so, it can yield positive outcomes for eligible young workers, their families, communities, employers, and DC’s economy.

In order to redress deep and chronic racial inequities in the labor market and advance racial and economic justice, the job guarantee’s north star goals should be to 1) eliminate involuntary unemployment among eligible young workers, prioritizing those most in need, 2) connect eligible young workers to a meaningful, high-quality guaranteed job and immediate earned income, and 3) ensure greater success with robust services and supports. A youth job guarantee must also establish safeguards aimed at ensuring employers do not exploit access to subsidized labor, limiting the extent to which public dollars subsidize private, for-profit firms, and protecting existing workers from displacement.

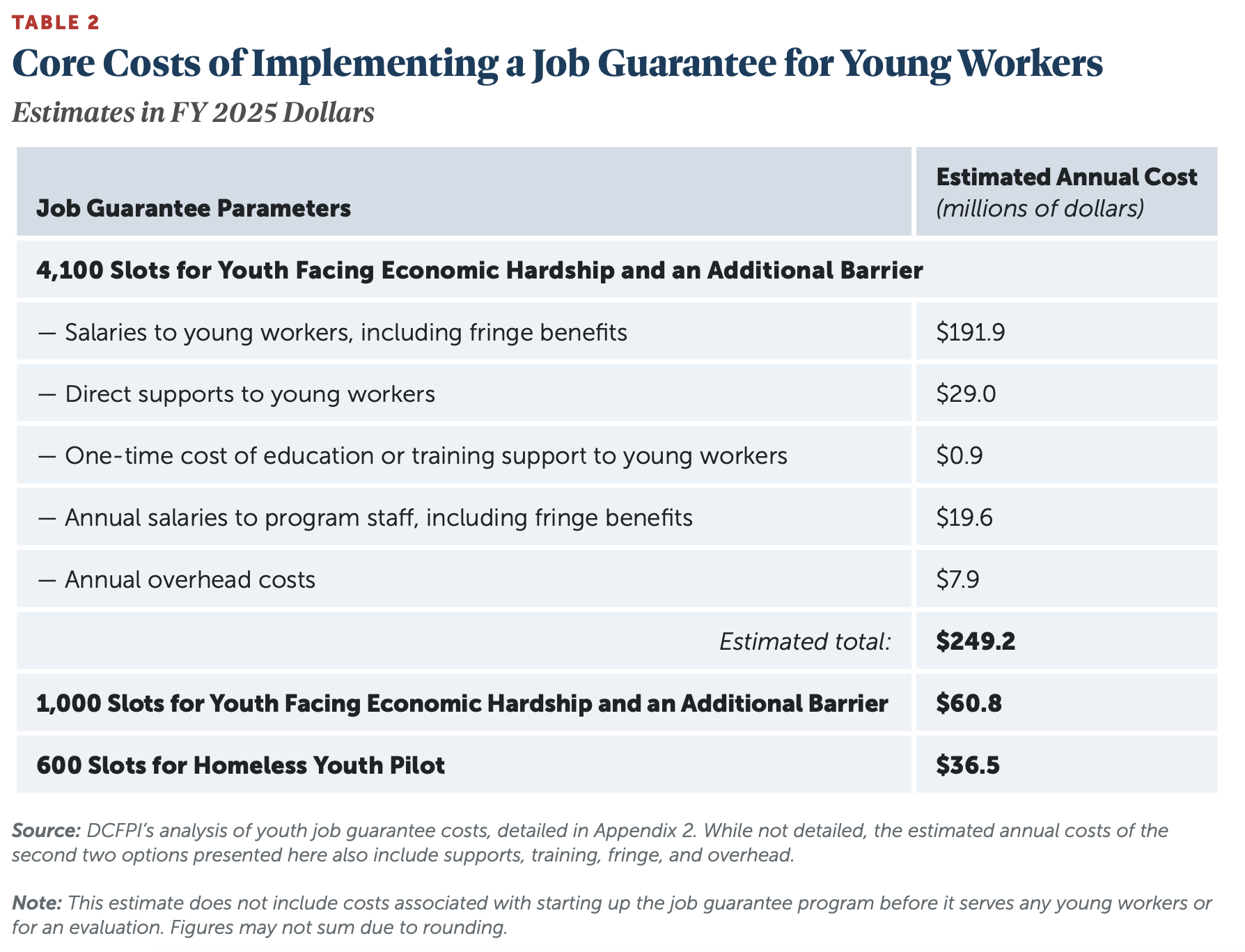

A job guarantee program that places 4,100 young workers in full-time work for one year would cost the District an estimated $249 million in fiscal year (FY) 2025 dollars annually. This estimate is dynamic, and can be dialed up or down, depending on the number of young people served and their hours worked.[2] For example, a job guarantee for 1,000 full-time young workers will cost an estimated $61 million, while a job guarantee for a small pilot of 600 workers would cost $37 million.

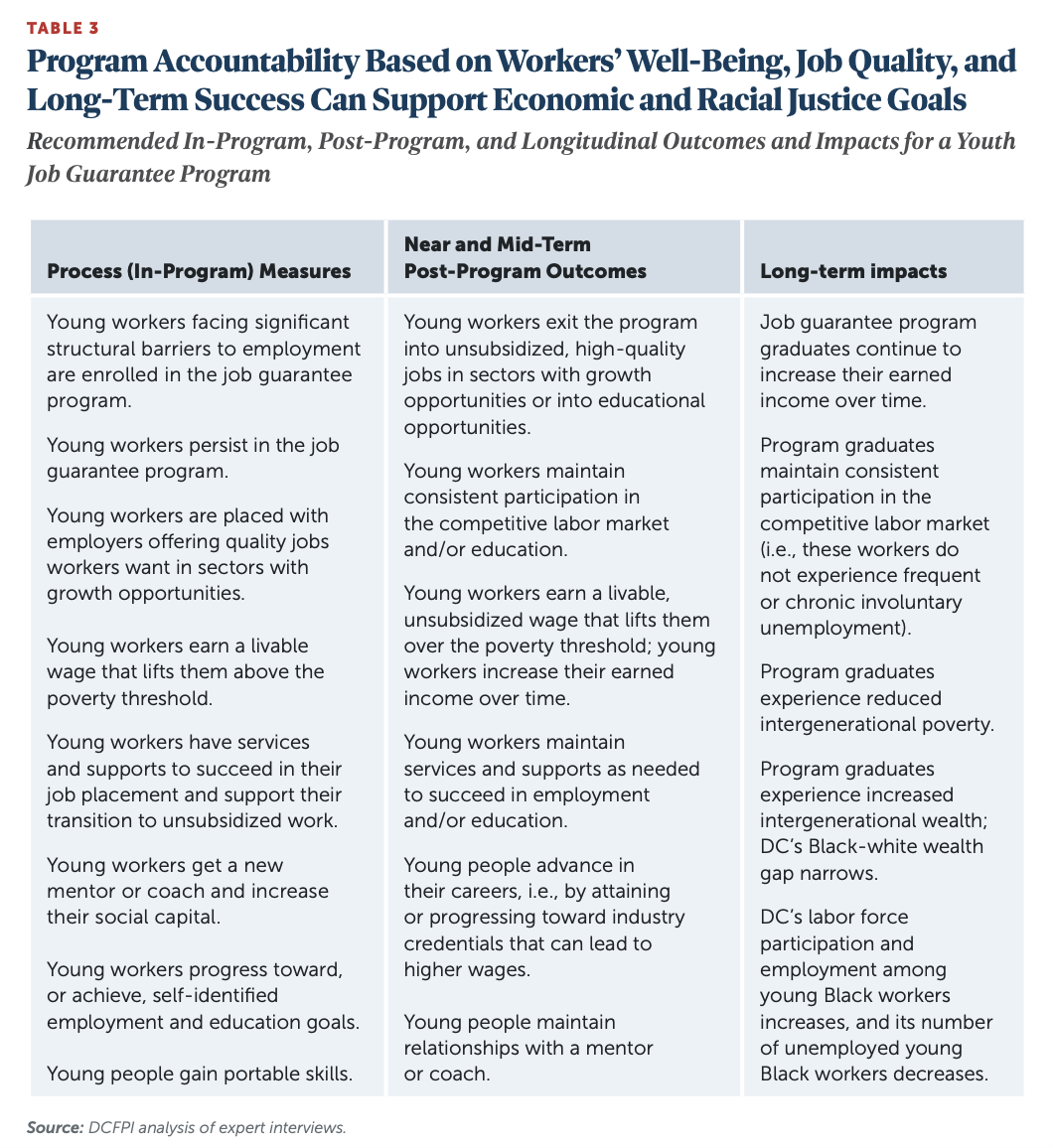

Policymakers should also develop and measure progress toward in-program measures, post-program outcomes, and long-term impacts.[3] Oversight and accountability mechanisms, including those that promote public transparency, can help center young workers in program decision making, hold program administrators responsible to program improvements, and promote the job guarantee’s overall success.

Ensuring that young workers who face structural barriers to employment are guaranteed a quality job, coupled with supports to help them succeed, can go a long way toward correcting deep racial inequities in the labor market and build a more robust economy in which all workers are fully included.

Table of Contents

- Young Workers Experience Chronically Higher Rates of Unemployment and Are More Subject to Economic Downturns than Prime-Age Workers

- Deep Racial Disparities in Employment Exist Among Young Workers in DC

- Systemic Racism is at the Root of Structural Barriers to Employment for Young Black Workers

A Youth Job Guarantee Can Benefit Young Black Workers, Their Families, Communities, and DC’s Economy

A Youth Job Guarantee in DC Should Prioritize the Young Workers Most in Need

- A Youth Job Guarantee Should Provide Young Workers Stable, Well-Paid, and Quality Jobs

- Robust Services and Supports for Young Workers Are Essential, and the Job Guarantee Program Should Leverage DC’s Existing Social Service Ecosystem to Provide Them

The Estimated Cost for A District Youth Job Guarantee is Flexible Based on Size of Program

Measuring Progress and Outcomes Is Essential for Accountability and Success

A Youth Job Guarantee Should Be Held Accountable to its Goals Through Process Measures and Outcomes

- A Youth Job Guarantee Needs Program Safeguards to Mitigate the Risk of Exploitation, Reduce the Extent to Which Private Firms Benefit, and Protect Existing Workers

- Through Oversight and Accountability Mechanisms, a Youth Job Guarantee Can Stay on Track Toward Its Goals and Outcomes

Appendix 1: Youth Focus Group Questions

Appendix 2: Methodology for Cost Estimate

Key Definitions

The youth labor force participation rate measures the share of 16- to 24-year-olds who have or are actively seeking a job, signaling overall economic health.[4]

The youth employment-to-population ratio, or the employment rate, measures the share of all 16- to 24-year-olds with jobs.[5]

The youth unemployment rate is the share of 16- to 24-year-olds in the labor market who do not have a job and are actively seeking work. This official unemployment rate likely underestimates the share of youth who want to work, as it only captures young people who have looked for work in the last four weeks.[6]

Young people who want a job, are available to work, and have searched for work in the last 12 months but not in the last four weeks are not considered part of the labor force nor counted in the youth unemployment rate. These marginally-attached young workers include: 1) youth who are discouraged about their job prospects (“discouraged workers”) for reasons such as there are no jobs available to them, they have struggled to find work in the past, they lack the education, training or experience necessary for jobs, or they are subject to discrimination and 2) other young people marginally attached to the workforce, who may be facing job search barriers such as caregiving responsibilities or illness.[7]

Prime-age workers are workers ages 25 to 54 years old.[8]

Subsidized employment is a workforce development approach that uses public funds to pay for some or all of workers’ wages, reducing the cost to employers of hiring workers and increasing demand for those workers.[9] Transitional jobs, a subset of subsidized employment, are targeted to workers facing structural barriers to employment and include supportive services to help workers transition into competitive jobs.[10]

Employment social enterprises (ESEs) are mission-driven businesses that employ workers facing structural barriers to employment, offering these workers transitional jobs, training, and skill building opportunities in the production and sale of goods and services.[11] ESEs reinvest the money into their businesses and workers and provide workers with supportive services and job search assistance.

A federal jobs guarantee provides public sector jobs to all workers ages 18 and older who want one and pays workers a non-poverty wage with benefits in order to eliminate involuntary unemployment and working poverty, lift the labor market floor by compelling private firms to offer a job at least as good as the public option, grow the tax base, and provide socially beneficial goods and services, among other macroeconomic benefits.[12]

Note: Youth and young workers are used synonymously throughout this paper.

Youth Are Less Connected to Employment, With Big Barriers for Young Black Workers Due to Systemic Racism

Young Workers Experience Chronically Higher Rates of Unemployment and Are More Subject to Economic Downturns than Prime-Age Workers

Young people face challenges getting and keeping work compared to workers ages 25 and older, both at the national and local level and in DC, young Black workers face chronic labor market exclusion. From 2021 to 2023, an estimated 4,100 District youth ages 16 to 24 years old were unemployed, of which, on average, about 71 percent (2,900 young people) were Black.[13] This official youth unemployment count likely underestimates the number of young people who want to work or who are structurally excluded from the labor market, because official unemployment data only captures job seekers who have searched for work in the last four weeks.[14]

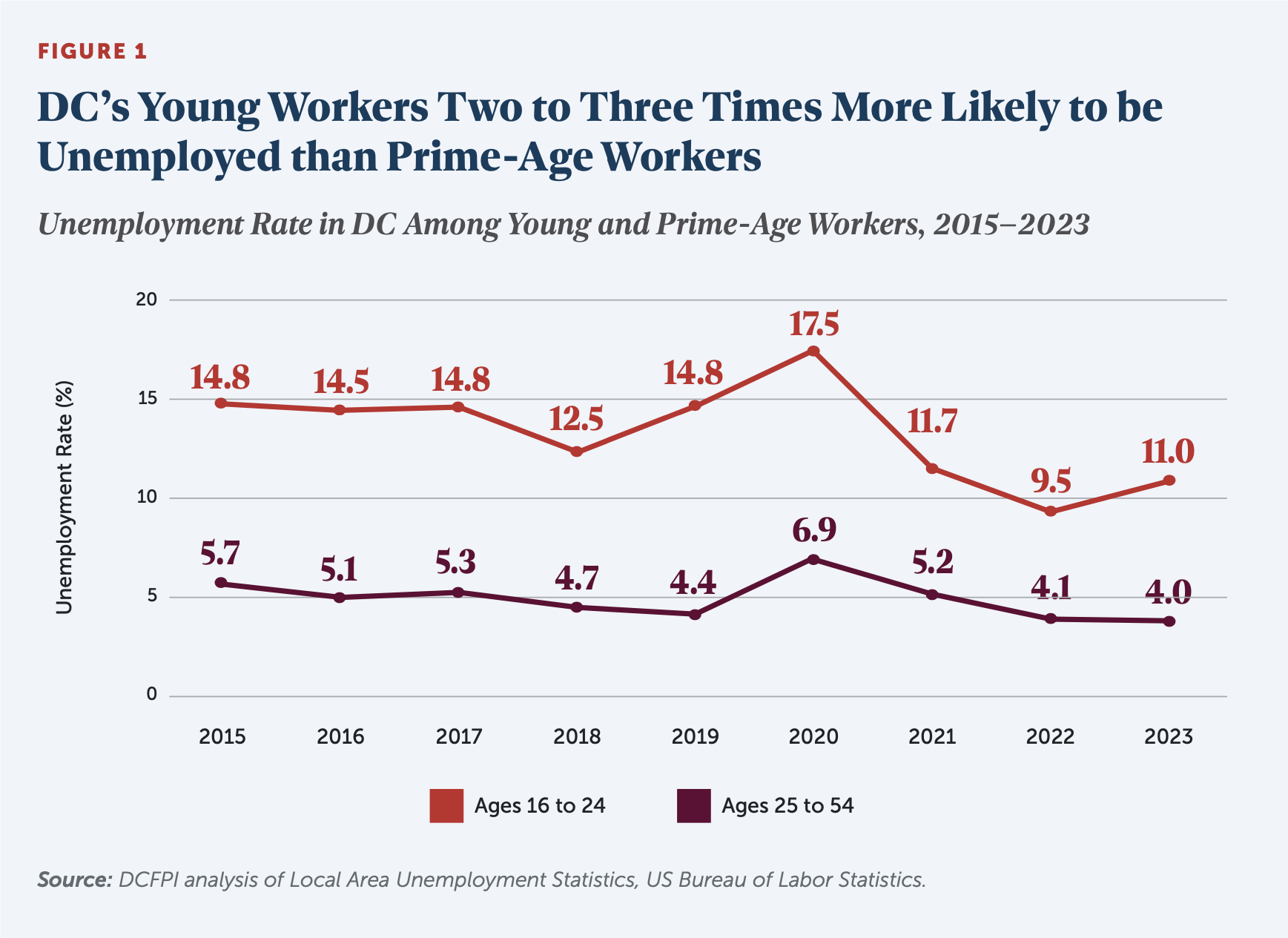

Outsized rates of unemployment among young workers compared with prime-age workers date back to the earliest data on youth unemployment.[15] Over the past several decades, young workers ages 16 to 24 faced an unemployment rate that was about 2.6 times higher than workers 25 and older.[16] In the District, for the better part of the last decade, the unemployment rate among young workers has ranged from 2.3 to 3.4 times higher than prime-age workers (Figure 1). In 2023, the unemployment rate for young workers in DC was 11 percent compared to 4 percent among their prime age counterparts.[17],[18]

Higher unemployment among young workers stems from their comparatively limited employment experience, the need for additional education or credentials, and increased vulnerability to labor market downturns.[19] Nearly half of all civilian jobs required prior work experience, nearly 20 percent of civilian jobs required a Bachelor’s degree, and 45.2 percent required credentials such as a certification or license, according to recent national surveys on occupational requirements by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.[20],[21] These requirements set high bars to entry that can result in exclusion of young workers just trying to get a start in the labor market, and likely the bar is higher in the District due to its high concentration of “white-collar” jobs.[22]

Young workers who find employment may also struggle to maintain it. For example, many young people in their first years of working are still developing the skills and capabilities needed for long-term labor market success, such as interpersonal communication, self-confidence and awareness, emotional management, and consistent work effort.[23] Within the competitive labor market—and especially among employers not well-equipped to work with young people—a young worker developing these skills may struggle to keep a job and end up cycling through periods of unemployment.[24]

Young workers are also less protected and more vulnerable to layoffs in economic downturns than older workers with more experience and tenure.[25] For example, the unemployment rate skyrocketed for 16-24-year-olds during the Great Recession and peaked twice as high as for prime-age workers.[26] This trend holds locally, with young workers in the District seeing unemployment reach 17.5 percent, compared to 6.9 percent among prime age workers, in 2020.[27]

Deep Racial Disparities in Employment Exist Among Young Workers in DC

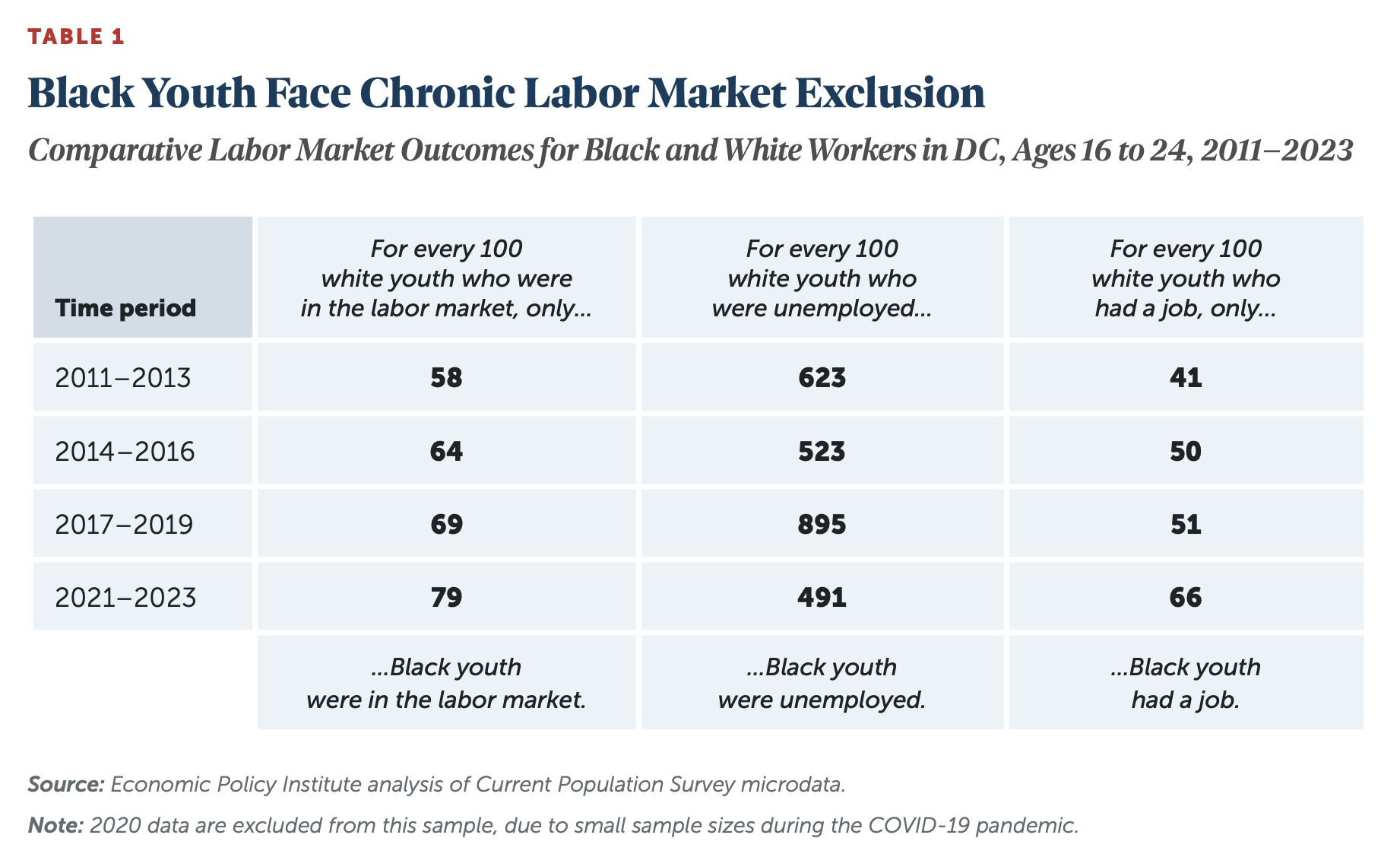

Due to historic and ongoing racism, exploitation, and discrimination in the labor market, which have led to the systemic exclusion of Black workers and non-Black workers of color from employment and economic opportunity, deep and chronic racial disparities exist in unemployment and other key indicators in DC (Table 1).[28] These disparities reflect that young Black workers are far more likely to experience significant structural barriers to work than their white counterparts.

DC’s labor market data also suggest that the existing youth workforce ecosystem is falling short of meeting the employment needs and interests of young Black workers in particular—and has been for some time.

In the District:

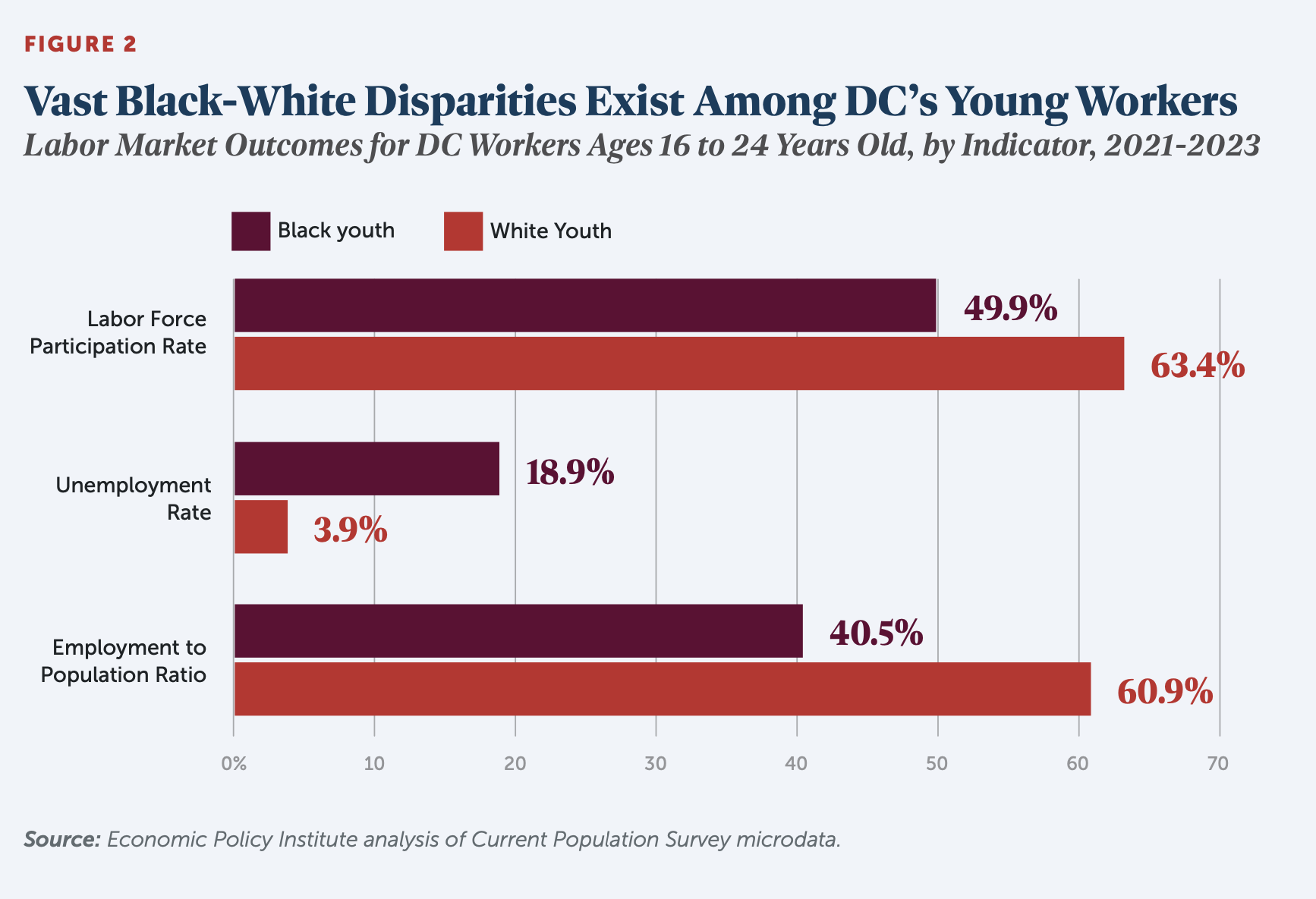

Fewer Black youth are seeking or have a job than white youth. Although DC is on par with the US for overall youth labor force participation rates, racial disparities are starker in DC. On average from 2021 to 2023, only 49.9 percent of DC’s Black youth participated in the labor market compared to 63.4 percent of white youth—a gap that is 6.1 percentage points larger than the national gap (Figure 2).[29]

DC’s Black-white youth unemployment ratio is nearly 5-to-1. DC’s average youth unemployment rate for young workers from 2021 to 2023 was 11 percent compared to 8.6 percent nationally. During this timeframe, the Black-to-white unemployment ratio for young workers nationally was about 2-to-1. Unemployment among DC’s young Black workers was nearly 19 percent, meaning that nearly 1 in 5 young Black workers was looking for but unable to find a job. By comparison, the unemployment rate among DC’s young white workers was just 3.9 percent—making DC’s Black-to-white youth unemployment ratio nearly 5-to-1.

Less than half of DC’s Black youth are employed, compared to about 60 percent of white youth. The rate of employment for young Black workers was just 40.5 percent, on average from 2021 to 2023. By comparison, 1.5 times as many (nearly 61 percent) young white workers were employed. Nationally, the US Black-white youth employment gap was narrower than DC’s during this time frame, signaling less racial disparity nationwide.

Young Black workers face chronic labor market exclusion. Young Black workers consistently have worse labor market outcomes than their white peers. Over the last decade, the average Black youth unemployment rate never dropped below 18 percent and was as high as nearly 33 percent in the wake of the Great Recession (2011 to 2013). Comparatively, unemployment for young white workers in DC has hovered between just 3.2 percent to 5.2 percent.

Systemic Racism is at the Root of Structural Barriers to Employment for Young Black Workers

Unjust and inequitable policies and practices, rooted in racism, have resulted in a greater likelihood that young Black residents experience poverty, homelessness, community-level violence, the foster care system, and the carceral system. These factors serve as barriers to employment. For example:

- Experiencing poverty contributes to and reinforces structural barriers to work, while access to wealth can mitigate these barriers. In DC, Black residents are 6.2 times more likely to experience poverty than white residents, the most recent Census data show.[30] Racial disparities in DC’s poverty rates are chronic and experiencing persistent childhood poverty can diminish future employment. Only about 35.4 percent of children who experience persistent poverty are consistently employed between ages 25 and 30 years old, compared to 70.3 percent of children who did not experience poverty, according to an analysis of more than 40 years of national data.[31]

- Due to the racist origins of the juvenile justice system, its overreach into communities of color, and its racially disparate response to youth of color, DC’s Black youth are significantly more likely to become justice-involved than young people of any other race.[32] Having a criminal record is a significant barrier to employment and being Black compounds that harm due to persistent racial discrimination in the labor market. White applicants with a criminal record are more likely to get a call back for a job than Black applicants without a criminal record, a widely-cited field experiment found.[33] In this study, the detrimental effect of having a criminal record was 40 percent larger for Black applicants than white applicants.[34]

- Inequities within DC’s foster care system also reflect systemic racism. In FY 2023, more than 80 percent of children in DC’s foster care system were Black while just 1 percent were white.[35] Foster care conditions result in challenges for youth like instability in placements, inconsistent educational arrangements, weak connections to kin and community, and lack of material supports. These factors contribute to higher rates of disconnection from school and work for young people with foster care histories, and lead to lower employment rates and earnings than attained by their non-foster peers.[36]

- Historic and ongoing racism and segregation in DC’s school system have led to educational differences by race that affect employment. In DC, Black students often do not get the resources they deserve, and many leave school without the tools needed to thrive in college or start a good career—upholding generations of racial and socioeconomic disparities.[37] However, even when Black workers have the same educational opportunities and credentials as white workers, employment and pay disparities persist because of racial bias and discrimination.

- As a result of the District’s racist housing policies and lack of affordable housing, young Black residents experience outsized rates of homelessness.[38] Among 18- to 24-year olds, 80 percent of single youth experiencing homelessness are Black and 95 percent of youth who head families experiencing homelessness are Black, according to the 2023 DC Youth Count.[39] Young people experiencing homelessness face barriers to work ranging from struggling to find stable housing to needing internet access to apply for jobs.[40]

Along with persistent, well-documented racial bias within the labor market among employers across recruitment, hiring, and pay decisions, these factors leave many young Black workers facing interrelated and compounding structural barriers to employment like unstable housing; unaffordable child care; limited transportation access; food insecurity; limited access to mental or behavioral health care supports; and criminal legal system involvement. [41],[42] Intersections with young parenthood, LGBTQI+ and gender non-conforming identities, disability, chronic illness, or mental health conditions further heighten the structural barriers to employment that systematically sideline young Black workers in the labor market.[43] Sometimes these barriers lead to outright disconnection. In DC, 31.4 percent, or about 1 in 3, Black youth ages 16 to 24 are neither in school nor working—the highest share of disconnected young Black people in the country.[44]

Finally, because Black households have been systemically denied opportunities to build wealth for generations, white households in the DC area hold 81 times more wealth than Black households.[45] Wealth allows young workers to weather a job loss, seek higher education, start a business, or leave or say no to a job that does not meet their needs and goals.[46]

A Youth Job Guarantee Can Benefit Young Black Workers, Their Families, Communities, and DC’s Economy

Labor market inequities among young workers have negative ripple effects, exacerbating barriers and holding back their economic security and DC’s economy. Unemployment harms young workers in immediate ways. In focus groups DC Action led for this report, discussed below, participants shared that when unemployed, they experienced housing instability, resorted to unsafe work, or struggled with depression and suicidal ideation. For these young residents, the harms of unemployment became self-reinforcing barriers to work, threatening to prolong bouts of labor market exclusion.

Experiencing unemployment or disconnection as a young person can also have long-term negative repercussions for these workers’ economic security and overall well-being. Experiencing unemployment between the ages of 16 and 23—especially as the period of unemployment grows longer—can lead to reductions in wages that are still evident in workers’ 30s and even early 40s.[47] Among workers from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, unemployment in one’s 20s is associated with lower job quality at age 29, resulting in being stuck in jobs with low wages, few benefits, or too few hours.[48]

The fiscal and social costs of chronic youth unemployment and disconnection are significant. For example, youth disconnection from work or school is associated with increased rates of substance use, worse health outcomes, and increased criminal activity.[49] These and other negative outcomes translate into decreased tax revenue and increased taxpayer costs tied to the provision of health care, basic assistance, and criminal legal system costs.[50] The full cost of youth disconnection to the economy, which takes into account workers’ lost wages and lost productivity, among other factors, has been estimated by one study at $52,042 annually, per disconnected young person (in 2024 dollars) until age 25 and $735,155 across the lifespan.[51]

While youth unemployment causes near and long-term harm, connecting youth to employment yields near and long-term benefits. In the near term, employment puts much-needed earned income into young workers’ pockets, helping youth afford rent, food, and other basic needs. Earning a paycheck may also qualify a young worker for the Earned Income Tax Credit or the Child Tax Credit, further supporting financial stability and benefitting young workers’ children.[52]

Among workers from economically disadvantaged backgrounds—who, in DC, are disproportionately Black—having a job as a teenager predicts higher job quality in adulthood, pointing to the longer-term benefits for young workers and the economy overall.[53] By their 30s, young people who are connected to work or school in their teens and early 20s are likelier to be employed, earn more money, own a home, and report being healthier than their disconnected peers.[54]

A Job Guarantee Would Foster Connection, Address Barriers, and Boost the Economy

A DC youth job guarantee, which would quickly connect young people who want to work with a job with a livable wage, benefits, and supportive services, can yield positive outcomes for eligible young workers, their families, communities, employers, and DC’s economy. Because the US has not implemented a recent or robust job guarantee for either youth or adults, evidence from subsidized employment evaluations can serve as a proxy for the likely benefits of a local job guarantee program.[55] Subsidized employment programs, in which the government or another entity temporarily subsidizes some or all of an individual’s wages, have been widely evaluated and share similar goals to a job guarantee: Namely, to provide people who would not otherwise be working with rapid connections to employment and earned income.

During recessionary periods, subsidized employment strategies can reconnect workers to the labor market, stave off large-scale job loss, and stabilize the economy.[56] During periods of economic growth, these strategies have traditionally supported positive employment outcomes for workers facing chronic labor market disconnection.[57] For decades, federal, state, and local governments, including the District, have implemented subsidized employment strategies. Fifty years of evidence for subsidized employment, including evidence from large-scale, rigorous evaluations, demonstrate that subsidized employment strategies are often cost effective and yield a range of benefits.[58]

Subsidized employment and transitional jobs programs have been shown to:

- Rapidly connect people who would not otherwise be working to jobs, putting earned income in the pockets of those who need it most, and boosting financial stability: High levels of voluntary participation across rigorously-evaluated subsidized employment programs show that many people currently excluded from the labor market want to, can, and do work when offered low-barrier work opportunities.[59] Program evaluation data also suggest that young people’s subsidized employment earnings can improve their household’s financial stability. For example, an evaluation of a transitional jobs program in Chicago found that, on average, the monthly income earned by young workers boosted their household’s pre-program income by 78.5 percent.[60] Over 60 percent of those young workers were their household’s sole earners at program entry.[61]

- Increase employment, reduce poverty, and benefit workers’ children for years: Among families with low incomes, parents’ participation in a three-year economic opportunity program that provided transitional jobs and robust economic and social service supports resulted in these workers having more stable employment, lower rates of poverty, and higher wages five years after program entry compared to their nonparticipant peers.[62] Additionally, even five years after program entry, parents’ participation improved their children’s positive social behavior and school performance, demonstrating powerful two-generation benefits.

- Foster safer communities through reducing recidivism and arrests for violent crimes: Among people returning home from incarceration, transitional jobs participation can significantly reduce recidivism, especially among those at higher risk of recidivism.[63] In one study of the Center for Employment Opportunities’ (CEO) transitional jobs program for returning citizens in New York City, reincarceration rates among workers less than 29 years old were a full 10.8 percentage points lower than among their control group peers.[64] In a different study, participation in a paid summer jobs program decreased violent crime arrests by 43 percent among Chicago high schoolers (ages 14 to 21 years old) from economically marginalized backgrounds compared to their nonparticipant peers.[65]

- Improve business outcomes and performance: Employers who participate in subsidized employment and transitional jobs programs have reported that doing so helped them expand or grow their workforce at reduced cost, increase business productivity and profits, and improve customer satisfaction.[66]

- Increase consumer spending power, bolstering local economies: Subsidized employment quickly connects workers to earned income, increasing their spending power. An evaluation of a Chicago-based transitional jobs program that employed about 1,500 adult and youth workers for just four months estimated that workers’ increased consumer spending generated about $6.3 million in new economic activity across Cook County and resulted in 44 new jobs due to increased demand for goods.[67] Similarly, evidence from national subsidized employment programs shows that workers spend the money quickly in their communities, boosting the local economy, and that the programs contribute to small business stability and expansion.[68]

- Be cost effective in a wide range of settings: By reducing the long-term costs of unemployment and disconnection, the benefits of subsidized employment programs often outweigh the costs.[69] For example, for CEO’s transitional jobs program, the financial benefits to taxpayers outweighed the costs by about 3-to-1, largely in the form of reduced criminal legal system expenditures.[70] More recently, research estimated READI Chicago—a subsidized employment program for men at highest risk of gun violence—generated up to $916,000 per participant in social savings from reduced shootings and other violent crimes, an 18-to-1 cost-benefit ratio.[71]

Young Workers Weigh In: Focus Groups with District Youth Experiencing Structural Barriers to Employment

To better understand the lived experience of young workers facing structural barriers to work, and to inform the job guarantee design, DCFPI partnered with DC Action to conduct youth focus groups over the summer of 2023. DC Action is a local non-profit with youth expertise that aims to break down barriers that stand in the way of all kids reaching their full potential.

DC Action led four focus groups with a total of 26 young people (ages 14 to 24 years old). The focus groups took place at the Healthy Babies Project, SMYAL, Black Swan Academy, and DC NEXT! Eighty-eight percent of focus participants identified as Black, and 90 percent identified as a person of color. These young people faced employment barriers including experiencing economic hardship, homelessness, being pregnant or parenting, identifying as queer and/or trans, having limited access to child care and transportation, and having limited work experience coupled with lack of access to mentorship or coaching.

DC Action staff asked focus group participants questions about their career dreams, finding and keeping jobs in DC, the harms of unemployment, and how a job guarantee program should be designed to meet their needs and interests. The full set of questions are in Appendix 1. Major findings from the focus group include:

Young people want to be business owners, doctors, and lawyers, but need a range of supports and services to mitigate barriers and help them achieve their goals. Many focus group participants shared that they wanted to be business owners, doctors, attorneys, investors, advocates, and engineers. Others wanted to be nurses or flight attendants, among other career paths. Many of these career paths require advanced degrees, certifications, and specific occupational or entrepreneurial skills. However, young workers faced challenges to achieving these goals due to experiencing structural barriers to work. They struggled with economic hardship, education opportunities, lack of child care, inflexible scheduling and insufficient work hours, lack of transportation and geographically inaccessible workplaces, lack of accommodations for disabilities, and discrimination based on sexuality, race, and age. They reported interpersonal barriers due to degrading communication and culturally incompetent employers. Young workers also felt that there are not enough jobs available to youth in the competitive labor market, especially good quality jobs with employers who are invested in seeing youth succeed.

Young people named supports and services that they believe are responsive to their lived experiences and essential to helping them meet immediate needs while achieving their career goals, including: support with child care and transportation needs; housing supports; access to mental health care; mentorship, including mentorship focused on achieving entrepreneurial goals; on-the-job training; connections to additional training and education programs, including support with obtaining scholarships; financial literacy courses; and peer support to navigate the day-to-day challenges of work, among others.

Involuntary unemployment harms young workers and creates cycles of disconnection from work. Young workers shared that interruptions and disconnection from work kept them from meeting their basic needs. They experienced housing instability, resorted to unsafe work including sex work, and struggled with depression and even suicidal ideation. Young people described feeling “alone and isolated” and “overwhelmed” when unemployed and called the experience of unemployment traumatic. For these young workers, the harmful consequences of unemployment could result in or amplify barriers to work, threatening to become a self-reinforcing cycle.

Young people want jobs that align with their interests, skills, and goals, and would benefit from working with employers who are equipped to support youth. Many young workers shared negative experiences about their time in the competitive labor market. Some expressed that the jobs available to them were intensively customer-facing and did not always align with their interests or strengths, resulting in stress. This was especially true for neurodivergent youth. Young workers also felt discouraged that available jobs did not advance their career goals, sharing, “the world needs to be built on more than people who are baristas, line cooks, and waiters. There [have] to be other ways to get your foot in the door.”

Beyond feeling mismatched to available jobs, young people’s experiences indicate that the competitive labor market offers youth jobs that are low quality, if not downright detrimental to their well-being. Young workers shared that employers failed to pay living wages; offered them little flexibility to work around other life commitments or needs, such as caregiving responsibilities; fired them after becoming pregnant; failed to provide proper accommodations; and, that they experienced harassment or discrimination on the job based on their race or gender identity.

Finally, focus group participants shared that they had worked for employers who lacked effective communication skills with young people and assumed that young workers were irresponsible. Employers’ ineffective communication or biases, in turn, gave rise to workplace conflicts and job termination, pushing young people back into the cycle of unemployment.

Youth are interested in well-paid, year-round work experiences that support their career trajectory, and feel existing public workforce offerings fall short. Young workers discussed existing youth employment opportunities available through the Department of Employment Services (DOES). Young workers expressed that while the Marion Barry Summer Youth Employment Program (MBSYEP) makes it easy to access a job, MBSYEP’s low pay was a strong disincentive to participation—especially when they saw workers in similar roles in the competitive labor market earning more. Reflecting on the pay, one young person said, “My SYEP job is an ice cream [shop] job, and I only get paid $9 per hour [while] other people make more.” DC’s current minimum wage is currently $17.50 an hour (up 50 cents since the focus groups took place). Another young person felt that due to the low pay, MBSYEP was “a waste of time.”

Beyond the pay, youth shared that existing workforce programs had matched them to jobs that didn’t align with their career interests. Young workers stressed the importance of having programs pair them to jobs and industries they want to work in. Young workers said that they “want experience with something that is going to be useful” and not “arbitrary” roles.

Finally, youth said they need job opportunities year-round. As one young worker said, “You should be able to get employment all year, not just in the summertime, even if you’re young.”

An Equitable Jobs Guarantee that Advances Economic and Racial Justice Would Prioritize Those Most In Need and Connect Them with High-Quality Jobs and Services

A youth job guarantee should advance racial and economic justice in DC by redressing deep and chronic racial inequities in the labor market and increasing economic opportunity among young workers of color, especially young Black workers, experiencing significant structural barriers to employment. DC’s current programs fail to do so. For example, DC’s transitional jobs program is highly limited in its reach and does not specifically focus on young workers. While DC’s summer youth employment program primarily serves Black youth, it offers short-term, seasonal work only and is not necessarily aligned with the needs or aspirations of young people; it also offers sub-minimum wage pay and there is not strong evidence for the program’s efficacy relative to standard workforce development outcomes. Moreover, these opportunities do not provide wrap-around supports responsive to the structural barriers youth facing hardship experience.[72],[73]

To achieve this vision, the job guarantee’s north star goals should be to:

- Eliminate involuntary unemployment among eligible young workers, prioritizing those most in need.

- Connect eligible young workers to a meaningful, high-quality guaranteed job and immediate earned income.

- Ensure greater success with robust services and supports.

A Youth Job Guarantee in DC Should Prioritize the Young Workers Most in Need

To achieve its vision and goals, a DC job guarantee must be designed to reach young workers facing the biggest structural barriers to employment. Because it is easier for workforce programs to default to serving workers who experience fewer barriers, a job guarantee open to all 16-to-24 year olds runs the risk of excluding young workers who face more significant barriers, including those who are truly disconnected and less able or likely to seek out programming. Narrowing program eligibility, along with identifying target populations for specialized outreach and an accessible, simplified application process, can help ensure services, supports, and public investment reach the young workers who could most benefit from the job guarantee.[74]

Although some form of eligibility requirement is necessary to put boundaries around the program, the job guarantee should aim for inclusion and reduce burdensome eligibility verification procedures as much as possible. Whenever feasible, participants should be able to self-attest to meeting eligibility requirements, as federal youth workforce programs allow.[75]

A DC program should prioritize:

- Young people who are unemployed and experiencing economic hardship, with a priority for those facing significant barriers to work: To advance racial and economic justice goals, a DC job guarantee for young workers could focus eligibility on unemployed workers ages 16 to 24 years old who are experiencing economic hardship and one or more barriers to work. While economic hardship is an employment barrier in and of itself, a job guarantee should prioritize young workers facing the most significant barriers. This could mean setting aside a percentage of job slots (e.g., no less than 75 percent of slots) for priority groups.

The priority groups could follow the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Youth Program guidelines, for example, focusing on young people experiencing homelessness, young people who have left school without a high school diploma or GED, pregnant or parenting youth, justice-involved youth, or youth within or aging out of the foster care system.[76]

To qualify for a job guarantee slot under this eligibility approach, a young person would need to be unemployed according to the standard definition, but the program also should extend to those marginally attached to the labor force.[77]

To ensure the job guarantee meets its target, program staff would need to engage in proactive, data-informed, and robust outreach to identify young people least likely to seek programming on their own. The job guarantee should avoid using a first-come, first-serve basis, especially for priority slots.

- Young people experiencing homelessness: For a small and highly targeted pilot job guarantee, lawmakers could narrow program eligibility to District residents ages 16 to 24 years old who are experiencing homelessness, meaning those in shelter or transitional housing programs, those in unsheltered locations, such as a park or sidewalk, and those who are “housing insecure,” as defined by the Interagency Council on Homelessness.

In 2023, about 1,046 unaccompanied young people in the District were experiencing homelessness, according to the most recent Homeless Youth Census.[78] About 98 percent of these youth were ages 18 to 24.[79] Black youth make up 80 percent of single youth and 95 percent of youth who head family households experiencing homelessness. Along with the trauma of homelessness, these youth report involvement in the foster care and juvenile justice systems, domestic and other forms of violence, mental health and substance use conditions, and limited educational attainment.

In DC, only 29 percent of single youth experiencing homelessness, and 24 percent of youth who head family households, reported having full-time employment in 2023. And these jobs are not yielding sufficient income for these workers to keep a roof over their heads.[80] Finally, DC’s existing youth workforce ecosystem is not reaching young people experiencing homelessness: A mere of 5 percent of single youth and 10 percent of youth who head family households said they were connected to a workforce program.[81]

A job guarantee that targets homeless youth could work through the Department of Human Services and the Interagency Council on Homelessness to identify participants. Young people should be allowed to self-attest to being homeless.

To Promote Inclusion of Young Workers Experiencing Significant Barriers to Employment, A Youth Job Guarantee Should Fully Subsidize Wages Across the Program Period

To advance racial and economic justice, a youth job guarantee must mitigate the risk of employer partners rejecting young workers who face the most significant structural barriers. Subsidized employment program approaches proven to help do this are those that:

- Fully cover wage and payroll costs for the length of the placement. This is because when workforce programs ask employers to take a worker onto their payroll—even a subsidized worker—they will treat that person as they would any other hire, holding the worker to standards that can exclude people facing significant employment barriers.

- Set minimal expectations around hiring post-subsidy. This can better serve workers facing significant barriers to employment.[82] As with pay, if employers are required or expected to hire on a subsidized worker after their subsidy ends, they are likely to be more selective among potential subsidized candidates up front, again running the risk that young people who face greater barriers will be excluded from roles. However, employers should be allowed to hire job guarantee participants, if they so choose.

In addition, to remove the administrative work of managing payroll and the “risk” associated with having employees (e.g., having to pay out unemployment or workers’ compensation claims), employer partners should not take young workers directly onto their payrolls, and instead a third-party intermediary, such as a non-profit or public agency, should act as the employer of record.

A Youth Job Guarantee Should Provide Young Workers Stable, Well-Paid, and Quality Jobs

A job guarantee should offer young workers a stable, well-paid, and high-quality experience. At minimum, the program should pay all young workers at least the District’s prevailing minimum wage.[83] Currently, DOES’s flagship MBSYEP pays workers ages 16 to 21 just $9 per hour.[84],[85]

Job guarantee workers should also, at minimum, qualify for the District’s existing worker benefits, such as paid sick leave and paid family leave. However, program administrators should prioritize partnerships with employers that offer more generous paid leave policies, health and dental insurance, and retirement savings plans. And, because job quality goes beyond a fair wage and benefits, administrators should prioritize employer partners that offer young workers developmental experiences.

Job placements should offer young workers up to 40 hours per week of paid work and work-related activities, eliminating the risk of insufficient work hours. At the same time, workers who need part-time work because they are in school or for other reasons should identify the number of hours that they want to work and be matched to appropriate jobs. Work-related activities for which young workers should receive compensation include their participation in activities such as work readiness or workers’ rights trainings, career coaching and case management, and education or training. In order to incentivize participation in work, lawmakers may want to consider placing a cap on the number of hours a young worker can be paid for work-related activities, e.g., up to 25 percent of their hours in the program.

Finally, the program must adhere to all DC laws related to the employment of minors, including hours of the day that minors can work.

A Youth Job Guarantee Should Offer Employment Opportunities Across Sectors, and Prioritizing Employer Partnerships that Offer Quality and Developmental Experiences

To ensure that guaranteed jobs meet young workers’ skills, interests, and career goals, a DC youth job guarantee needs flexibility regarding employer partners and available jobs. To this end, the program should include employer partners from the public sector, the non-profit sector—including employment social enterprises (ESEs)— and the for-profit sector. Having an array of employer partners means an array of jobs available to young workers, so that job guarantee participants can be paired to employment opportunities that “meet them where they are.” For example, a young worker with very limited job experience and significant employment barriers may benefit most by being matched to an ESE, where they can receive higher-touch supports and have more opportunities for on-the-job training, whereas an older worker may be better suited for a more independent role. Although a wide range of employers and jobs should be available, the job guarantee should prioritize the goal that available jobs benefit workers, people, and communities over profits for large, private firms.

In addition to prioritizing partnerships with employers that exceed DC’s wage and job quality floors, program administrators should prioritize employer partners that can demonstrate through worker feedback that they offer young workers a developmental work experience, such as through intensive supervision, coaching, skill development, and trauma-informed workplace practices.[86] By doing so, the job guarantee may shift employer behavior toward better serving young workers.[87]

To bolster worker power, the program also should seek to partner with unionized employers and allow young workers to become eligible for union membership. And, to advance racial and gender equity, the program should prioritize partnerships with Black, brown, or women-owned businesses, including those in Wards 5, 7, and 8.

A Longer Program Length May Best Support Young Workers Facing Significant Barriers to Employment

Subsidized employment and transitional jobs programs have a wide variety of intervention lengths, ranging from a few months to a few years.[88] Research suggests that longer programs, especially those with subsidies lasting more than 14 weeks, are more likely to increase employment and earnings over the medium- and long-term.[89]

For young workers facing significant employment barriers, a longer engagement period may be particularly helpful. For example, Roca—a transitional jobs program for youth ages 16 to 24 who have experienced extensive trauma and face significant employment barriers such as justice system involvement, limited or no work history, and low literacy—engages young people for four years.[90] Roca’s program data find that young people begin to experience change around 18 to 24 months into programming, and their transitional employment program anticipates and builds in opportunities for young people to be fired and re-hired multiple times.[91]

To account for meeting the developmental and service needs of young workers facing significant barriers, while also striking a balance around the fiscal realities of serving a large cohort of subsidized workers for an extended period, a DC youth job guarantee should offer young workers at least one year of paid work and work-related activities. At the end of a one-year period, young workers who continue to face barriers entering the competitive labor market, education, or training opportunities should be eligible to re-enroll for one additional year, so that the job guarantee does not leave these young workers behind.[92] In other cases, the program can help participants transition to next steps, like unsubsidized employment, educational opportunities, or industry-specific training pathways.

Robust Services and Supports for Young Workers Are Essential, and the Job Guarantee Program Should Leverage DC’s Existing Social Service Ecosystem to Provide Them

The job guarantee should provide young workers with wraparound services and supports to mitigate structural barriers to employment and increase success within and beyond the program. Research suggests that subsidized employment programs with wraparound supports are best positioned to improve employment rates and earnings.[93] Without supports and services, the job guarantee will set up some young workers to fail.

Supports and services should be responsive to each young person’s needs and interests, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, and should include a tailored mix of the following:

- Transportation supports such as WMATA passes or gas cards.

- Affordable and reliable child care, including financial support to cover the cost of sliding scale fees for day care, as well as assistance with child care access and parental resources.

- Housing supports, including financial support to mitigate rent burden as well as housing search assistance, connections to vouchers, roommate identification, landlord-tenant or roommate mediation, and more.

- Direct cash to young workers help cover the cost of household financial emergencies or solve other barriers to work.

- Work uniforms, supplies, or equipment necessary for workplace success.

- Workers’ rights trainings, to empower young workers to navigate workplace issues.

- Work readiness trainings, so that young workers can develop the skills and capabilities necessary for the workplace.

- Career navigation, coaching, and mentorship to prepare and support young workers for career pathways, training, and education after the job guarantee.

- Financial capability supports, such as budgeting support, banking access, credit repair, and tax filing assistance.

- Mental and behavioral health supports, to connect young workers with age-appropriate and culturally competent care.

- Education and training opportunities, including one-time financial support to partially cover the cost of pursuing educational or training opportunities as well as connections to these opportunities (e.g., literacy and numeracy skill building opportunities, GED courses, certifications, Associate’s or Bachelor’s degree programs, or occupational trainings to meet learning or career goals).

- Job retention and advancement supports to help young workers maintain unsubsidized employment and advance in the labor market.

- Case management and systems navigation to help young people navigate work challenges, access benefits, and leverage available public supports and services.

While the job guarantee should provide direct cash and other in-kind employment-related supports to young workers, the program does not need to create all supports and services from scratch. Instead, job guarantee administrators should partner with and leverage DC’s existing non-profit and public sector supports. Having an interagency approach to program administration can help ensure that cross-system collaboration aimed at providing workers with holistic supports is baked into program processes.

The Estimated Cost for A District Youth Job Guarantee is Flexible Based on Size of Program

To estimate a program cost, DCFPI considered a number of core costs for operating a robust job guarantee program, including the costs of 1) salaries to young workers; 2) direct supports to young workers, including a one-time support for education costs; 3) salaries to program staff; and, 4) program overhead costs.[94] Assumptions related to the inputs for these core costs are detailed in Appendix 2.

A job guarantee for DC’s estimated 4,100 officially unemployed young workers would cost DC up to an estimated $249.2 million per year in FY 2025 dollars per year to operate (Table 2). This cost assumes 100 percent participation and full-time, year-round work (or combined training and work) in a year-long program. In reality, a job guarantee program may not see all unemployed young workers participate, nor will all of these workers want or need work for 40 hours per week. In that sense, this estimate is dynamic, as it can be dialed up or down depending on the number of young people served and, to a lesser extent, the number of hours young people work. Actual costs may also fluctuate based on the specific set of direct supports each young person needs. Given the flexibility of cost, lawmakers can consider structuring the program at different scales and “dosages” of work, in order to align with an array of fiscal scenarios.

For example, one option might be to focus on unemployed youth experiencing economic hardship and one or more other major barriers to work but start the program with a goal of 1,000 participants. Once the program has enough data showing progress toward its goals, the job guarantee could expand over time to offer enough slots to cover the number of unemployed youth at that time. The cost for 1,000 slots would be $60.8 million.

Another route could be to pilot a job guarantee program for a small subset of young people, such as 600 youth experiencing homelessness over a two- to three-year period.[95] The annual cost would be $36.5 million. Implementing a job guarantee as a small pilot group of youth experiencing homelessness for three years could give the District sufficient time to see near and mid-term post-program outcomes.

While most of the cost in any scenario is salary and fringe benefits for young workers, the estimates also include robust investment in staffing. Program staff are critical to providing the depth of support, connection, and system navigability needed for transformative employment outcomes. The cost estimate includes three tiers of staff that are necessary to implement the program: 1) social and human service assistants; 2) social workers; and 3) social and community service managers. This staffing structure assumes that social and human service assistants lead the bulk of day-to-day, “on the ground” program implementation, with a smaller number of social workers in place as supervisors and/or staff who can step in as necessary to support young workers who may be in crisis or facing more significant barriers to employment. Social and community service managers serve in program leadership, oversight, and management roles.

It is beyond this report’s scope to estimate the indirect savings associated with ending or reducing chronic unemployment among young people facing structural barriers to work. As discussed, youth unemployment has high near and long-term costs, while subsidized employment programs yield positive benefits for individuals, families, communities, and businesses and are frequently cost-effective. Put another way, there are likely substantial cost savings associated with a high-quality employment intervention for young workers.

Measuring Progress and Outcomes Is Essential for Accountability and Success

A Youth Job Guarantee Should Be Held Accountable to its Goals Through Process Measures and Outcomes

To ensure the job guarantee program succeeds in meeting its goals, policymakers should develop and measure progress toward in-program measures, post-program outcomes, and long-term impacts (Table 3). These recommended success metrics differ from performance indicators mandated under WIOA.[96] WIOA performance heavily focuses on near-term unsubsidized employment and earnings outcomes, which incentivizes youth employment programs to focus on young workers facing fewer barriers.[97] WIOA performance indicators also do not capture the quality of subsidized or unsubsidized job placements, even as 1) job quality is important for worker well-being and economic security and 2) Black workers are overrepresented in lower-quality jobs.[98]

Policymakers also should measure the rate of job guarantee program take up among eligible youth. A high participation rate would indicate the program is meeting young workers’ needs and interests, with a low rate signaling the need for adjustment. Moreover, advocates could leverage a high work participation rate to shift narratives and perceptions among employers and other stakeholders about young people’s employability and willingness to work.

Finally, to promote accountability toward the program’s racial and economic justice goals, and to identify demographic trends in service provision and outcomes, the implementation agency should collect and publish participant data disaggregated by, at minimum, race and ethnicity, age, gender, ward, and income level at program enrollment. Administrators can use these data to course correct inequities.

A Youth Job Guarantee Needs Program Safeguards to Mitigate the Risk of Exploitation, Reduce the Extent to Which Private Firms Benefit, and Protect Existing Workers

The job guarantee benefits employer partners through subsidized workers.[99] To avoid employer exploitation of the job guarantee, and to limit the extent to which private, for-profit employers can benefit, the program should implement robust safeguards. These safeguards should also protect existing workers from displacement.[100]

Job guarantee program safeguards should:

- Limit participation of private, for-profit employers to smaller businesses. To help ensure that public dollars benefit DC’s smaller or legacy businesses, lawmakers should limit the size of eligible private employer partners, such as to businesses with fewer than 100 employees or by an annual revenue threshold.[101] DC’s larger for-profit firms can and should hire unsubsidized labor, including through existing pathways for young workers facing barriers.[102]

- Limit the extent to which private, for-profit employers can profit from the job guarantee program. The program should limit the total dollar amount of subsidized wages that benefit any private, for-profit employer partner. The total dollar amount by which a private, for-profit employer partner benefits could be determined via a formula that considers the employer’s size, annual revenue or profit, and other factors that incentivize participation from Black, brown, or women-owned businesses.

- Limit the percentage of an employer’s workforce that can be made up of job guarantee participants. To protect against employers structuring their workforce through subsidized labor, and to protect existing workers from displacement, employer partners should have a limited number of job guarantee slots for young workers. ESEs and non-profits with missions to offer low-barrier jobs to marginalized young workers should be exempt from this requirement.

- Limit the number of times an employer can serve as a worksite for guaranteed workers without directly hiring one these workers. Lawmakers should not require that employers directly hire participants in the job guarantee.[103] However, employers should not be able exploit a stream of free labor by never hiring a participant into an unsubsidized role. Placing a reasonable limit around how many times an employer can serve as a worksite without hiring (i.e., five times) can help strike this balance. ESEs and specific non-profits, described above, should be exempt from this requirement.

- Require regular site visits to employer partners and periodic evaluations to assess how well employers are serving young workers. A job guarantee should hold employers accountable for providing young workers meaningful work and learning. Regular site visits from program administrators and worker feedback evaluations can determine if employers are upholding the job guarantee’s vision and goals. The program should disqualify low-performing employers and prioritize high-performing employers. Young workers should help determine the employer evaluation metrics. The evaluation should also capture demographic data for the owners of the employers, retention rate, and time spent in the program.

Safeguards that protect existing workers from displacement should:

- Prohibit employer partners from replacing unsubsidized or striking workers with workers subsidized through the job guarantee. These actions run counter to the job guarantee program’s vision to advance racial and economic justice, and any employer partners that take these actions should be excluded from further participation.

- Gain labor union consent before finalizing employer partnerships. For potential employer partners whose workers are unionized, lawmakers should require the union’s consent before agreeing to the partnership.

- Ensure that employer partners do not infringe promotions for their existing, unsubsidized workers as a result of program participation. Policymakers should ask employer partners to attest that they will not place subsidized workers into more senior roles if doing so limits promotion pathways for their existing workforce. Employer partners should prioritize existing workers for promotions rather than time-limited subsidized workers.

- Ensure clear and enforceable procedures for filing and adjudicating grievances against employer partners. Lawmakers should ensure that the job guarantee program has processes in place for unsubsidized workers, unions, or others to report and adjudicate grievances against employer partners suspected of violating the program’s safeguards to protect existing workers from displacement.

Through Oversight and Accountability Mechanisms, a Youth Job Guarantee Can Stay on Track Toward Its Goals and Outcomes

Oversight and accountability mechanisms, including those that promote public transparency, can help center young workers in program decision making, hold program administrators responsible to program improvements, and promote the job guarantee’s overall success.

Job guarantee oversight and accountability mechanisms should:

- Start with a robust and inclusive program planning. Similar to WIOA practices, job guarantee administrators should undergo a planning process that documents how the District will 1) provide targeted outreach to identify and enroll eligible young workers and 2) ensure that the job guarantee’s services, supports, and employment opportunities align with young workers’ needs and interests.[104] Lawmakers should require that plans include input from eligible young workers.

- Center young people in program leadership and governance. The job guarantee program’s leadership and governance bodies should include eligible young workers and pay them for their participation to help ensure the job guarantee is relevant, responsive, and accountable to young workers. Program staff should offer trainings and support to equip young people to serve successfully. The program should also compensate any youth who support job guarantee design, implementation, or oversight outside of formal governance bodies.

- Require the program to track and report publicly on program success measures. In addition to DC’s performance oversight processes, the job guarantee should track and regularly report on program success measures through a public dashboard, allowing stakeholders to understand program performance in real time.

- Require periodic program evaluations to understand the job guarantee’s success. The program should undergo periodic, rigorous evaluations. Initially, the evaluation could focus on program implementation and program model fidelity. This would lay the groundwork for an impact evaluation aimed at finding evidence for the program’s effectiveness.[105]

Acknowledgments

Beginning in early 2023, DCFPI led 20 semi-structured interviews with nearly thirty national and local employment, youth workforce development, and economic opportunity experts. DCFPI interviewed youth employment program providers, advocates, researchers, economists, and government agency staff. DC Action also led four focus groups with a total of 26 young people (ages 14 to 24 years old) working with key youth partners.

DCFPI is grateful to all of the groups and people that provided their expertise, informing this report’s recommendations:

- Black Swan Academy: Focus groups

- The Brookings Institution: Martha Ross

- Center for Employment Opportunities: Casey Pheiffer, Simone Price

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: Donna Pavetti (formerly with CBPP), Catlin Nchako

- CLASP: Noel Tieszen, Kathy Tran

- Council of the District of Columbia Office of the Budget Director: Sam Rosen Amy

- DC Action: Amy Dudas, Mat Hanson, Kimberly Perry, Rachel White

- DC Central Kitchen: Dr. Beverley Wheeler, Ja’Sent Brown

- DC Department of Human Services: Bridgette Acklin, Jessica Bacon, Geoff King

- DC NEXT!: Focus groups

- Healthy Babies Project: Focus groups

- Institute on Race, Power, and Political Economy at The New School: Sarah Treuhaft

- The Intersect: Melissa Young

- Georgetown Center on Poverty & Inequality: Kali Grant

- Georgetown University: Dr. Bradley Hardy, Dr. Harry Holzer

- National Youth Employment Coalition: Thomas Showalter

- New Moms: Gabrielle Caverl-McNeal, Dana Emanuel

- REDF: Manie Grewal, Carla Javits

- Roca, Inc.: Lili Elkins

- Rutgers Law School: Dr. Philip L. Harvey

- SMYAL: Focus groups

- US Department of Labor: Molly Bashay, Ana Hageage, Stephanie Rodriguez

- William G. McGowan Charitable Fund: Chris Warland

Appendix 1: Youth Focus Group Questions

1) Which ward in DC do you reside? If not living in DC, where do you reside?

2) What is your favorite aspect of your community?

3) What is your dream job?

4) Tell us about your experiences looking for a job in the District.

5) If you’re currently unemployed, or if you’ve been unemployed in the past, how has this affected you?

6) Based on your own experience with work, or the experiences of family or friends, what do you see as the single biggest barrier to finding and holding down a good job in DC? Why?

7) Thinking about a time you were working, tell us about that job and your experience.

8) Let’s turn to the future. What are your dreams for your future career? How would your life change if you achieved these dreams? What supports do you need to help you achieve your dreams?

9) A guaranteed job program would quickly connect young people who want to work with a job with a livable wage, benefits, and supportive services so you can succeed in that job. If you were designing a guaranteed job program, what would it look like? [Follow on prompts: What types of jobs would be available? What supports would you recommend? How would you know the program was successful?]

10) What would you like policymakers to know about the interests and needs of young people looking for jobs in the District?

11) Are there other recommendations that you have, or suggestions you would like to make?

12) Are there other things you would like to say before we wind up?

Appendix 2: Methodology for Cost Estimate

To arrive at a cost estimate for a youth job guarantee program, DCFPI considered several core costs, including the costs of salaries to young workers; direct supports to young workers, including a one-time support for education costs; salaries to program staff; and the overhead costs associated with running a large-scale employment program. DCFPI made several assumptions related to these core costs. All costs were inflated to FY 2025 dollars in the body and tables of the report.

Salaries to Young Workers

The cost of salaries to young workers assume that workers are paid DC’s minimum wage of $17.50 per hour as of July 1, 2024, and adds on a fringe benefit rate of 25.3 percent, putting total salary at $21.93 per hour. This fringe benefit rate aligns with the rate for Department of Human Services (DHS) staff, and is part of overall employee compensation costs, including life and health insurance and retirement and Social Security contributions. The analysis defines full-time work as 40 hours of work/paid work activities per week over 52 weeks per year, meaning that a full-time worker would earn $36,400 per year in wages and cost about $45,609 per year to employ. The analysis defines part-time work as 25 hours of work/paid work activities per week over 52 weeks per year, meaning a part time worker would earn $22,750 per year in wages and cost about $28,506 per year to employ.

Direct Supports to Young Workers

Direct supports to young workers incorporated into this estimate include costs related to child care, housing, transportation, flexible funds to young workers, work uniforms or other supplies needed for a job, and financial incentives for meeting goals. The analysis assumes that program staff would provide other indirect supports—such as, for example, systems navigation, career coaching, or benefits counseling—and that therefore those supports are accounted for in staff salaries and overhead costs.

With regard to support for child care, the estimate includes the cost of covering co-payments for 25 hours of subsidized childcare services for a family consisting of one parent earning $36,400 per year who has one child in care. Co-payment costs are based on the Office of the State Superintendent for Education FY 2025 Sliding Fee Scale.[106]

With regard to support for housing costs, the estimate includes the cost of covering a portion of a young worker’s housing costs, aimed at reducing housing cost burdens. The analysis assumes a rent of $2,182 per month ($26,184 per year), based on reporting from the Office of Revenue Analysis for DC market rate rent in quarter one of 2024.[107] The analysis further assumes a young worker’s rent to be shared with one other person, reducing the cost to $1,091 per month ($13,092 per year). Finally, the analysis assumes the young worker is earning $36,400 per year, of which only one-third ($10,920 per year) should go toward rent and utilities in order to be affordable as defined by the Department of Housing and Urban Development and housing advocacy groups.[108] The cost for covering a portion of a young worker’s rent therefore covers the gap between estimated cost of rent ($13,092 per year) and estimated cost of affordable rent at a pre-tax wage of $36,400 per year ($10,920 per year).

One-Time Support for Education or Training Costs

The cost estimate includes one-time support for education or training costs, based on the cost of 12 credit hours ($1,834) toward an Associate’s degree at the University of the District of Columbia Community College (UDC-CC). UDC-CC tuition and fee costs are based on the costs for residents for fall 2023, the most up-to-date cost schedule publicly available at the time of analysis.[109] Twelve credit hours make up approximately 20 percent of the credit hours needed, on average, to complete an Associate’s degree, with an assumption that young workers can leverage other financing, such as scholarships or student loans, to complete a degree or other educational or training opportunity. Based on the interviews conducted for this report, it is unrealistic to assume that all young workers will want or need to use this support during their time in program. As a result, the cost analysis assumes that only one-third of young workers use this support throughout their time in the program.

Salaries to Program Staff and Staffing Ratios

The cost estimate for program staff salaries assumes three tiers of staff are necessary to implement the program: 1) social and human service assistants; 2) social workers; and 3) social and community service managers. This staffing structure assumes that social and human service assistants lead the bulk of day-to-day, “on the ground” program implementation, with a smaller number of social workers in place as supervisors and/or staff who can step in as necessary to support young workers who may be in crisis or facing more significant barriers to employment. Social and community service managers serve in program leadership, oversight, and management roles.

The profiles for these occupations, as well as their annual mean wage in DC, can be found via the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS).[110] This analysis uses the May 2023 OEWS estimates, which were released in April 2024. The analysis also applies a fringe benefit rate of 25.3 percent on top of the annual mean wage.

The cost estimate assumes the following staff-to-participant ratios, which are informed by the interviews conducted for this report: 1) one social and human service assistant for every 25 young workers; 2) one social worker for every 250 young workers (or, one social worker for every ten social and human service assistants); 3) one social and community service manager for every 125 young workers. Overall, under these staffing ratios, the analysis assumes one staff member for every 19 young workers.

Overhead Costs

At the recommendation of staff at the Council Budget Office, the estimate for overhead costs is derived by taking the FY 2024 approved non-personnel services (NPS) cost for the Office of the DC Auditor and dividing that cost by the number of approved full-time equivalent (FTE) positions to get an overhead cost of about $36,005 per FTE. The cost estimate assumes each program staffer is one FTE.

The NPS costs for the Office of the DC Auditor include standard items such as office space rental, IT systems, and office supplies, all of which would be necessary to operate the job guarantee program. The DC Auditor’s NPS costs also includes contractual services for studies, and therefore the cost of job guarantee program evaluation is partially baked into overhead costs. Unlike other agencies such as DHS or DOES, the Auditor’s NPS costs do not include costs associated with subsidies to residents, which are accounted for in the cost estimate via the salaries to young workers.

The cost estimate does not directly account for overhead costs associated with employer partners employing the young workers themselves, as these costs would vary from employer to employer. Moreover, some overhead costs—such as, for example, supplying a worker with a computer—may be covered through the direct supports to young workers. However, DCFPI assumes that employer partners would absorb a share of overhead costs associated with employing a young worker. Further, DCFPI assumes that a potential employer partner who had high marginal overhead costs would not opt into the job guarantee, as the benefits of doing so (i.e., fully subsidized labor) may not outweigh the associated overhead costs.

[1] Unpublished Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata, 2021-2023.

[2] Costs and details of all aspects of implementation of a job guarantee were beyond the scope of this proposal, but they will be important to the success of the program.

[3] It was not within the scope of this report to offer full detail on how a job guarantee should be implemented. These details will be critical to program success, but also depend on the program’s ultimate parameters.

[4] Economic Policy Institute, “Useful Definitions,” accessed September 5, 2024.

[5] Ibid.

[6] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey – Concepts and Definitions,” accessed August 1, 2024.

[7] Ibid.

[8] See, e.g., Cody Parkinson, “Labor Force Participation and Employment Rates Declining for Prime-Age Men and Women, ” US Bureau of Labor Statistics, July 2018.

[9] Algernon Austin and Annabel Utz, “Toward Black Full Employment: A Subsidized Employment Proposal,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, September 2022.

[10] Kisha Bird, “Transitional Jobs: Expanding Opportunities for Low-Income Workers,” Center for Law and Social Policy, October 2015.

[11] REDF, “What is an Employment Social Enterprise?,” June 2022.

[12] Mark Paul, William Darity, Jr., and Darrick Hamilton, “The Federal Job Guarantee – A Policy to Achieve Permanent Full Employment,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 2019.

[13] Unpublished Economic Policy Institute analysis of Current Population Survey microdata, 2021-2023.

[14] The official figures also include many young workers who move to DC to attend universities or to engage in internships or other work opportunities specific to the District. Unemployment for young workers born and raised in the District might look worse, if sample sizes allowed for that analysis.

[15] Laura Tatum, Indivar Dutta-Gupta, Cosette Hampton, Huixian (Anita) Li, and Peter Edelman, “The Youth Opportunity Guarantee: A Framework for Success,” Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, March 2019.

[16] Elise Gould, Jori Kandra, and Katherine deCourcy, “Class of 2023: Young Adults are Graduating into a Strong Labor Market,” Economic Policy Institute (Working Economics Blog), May 2023. [Note: This analysis is inclusive of workers ages 25 and older, not limited to prime age workers ages 25- to 54-years-old].

[17] In 2023, the average unemployment rate among youth nationally was 7.9 percent, compared to just 3.1 percent among prime age workers. US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Annual Averages – Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population by age, sex, and race – 2023,” January 26, 2024. [Note: DCFPI took the weighted average for unemployment among youth 16 to 19 years old and youth 20 to 24 years old].

[18] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics, “States: Employment status of the civilian noninstitutional population in states by sex, race, Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and intermediate age,” July 19, 2024.

[19] Ibid.

[20] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Requirements in the United States – 2023,” February 8, 2024.

[21] US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Requirements in the United States – 2022,” November 17, 2022.