The $1.9 trillion pandemic relief package passed by Congress in March–the American Rescue Plan (ARP)–is an unprecedented opportunity for the District to truly “build back better.” The District will receive at least $3.3 billion in direct federal relief funds, some targeted to specific needs like child care or schools, but most of it flexible dollars that can be used to address the deep harms of the pandemic. The ARP also provides substantial direct assistance to DC residents struggling to meet their basic needs. Rebuilding DC communities requires targeted and sustainable investments and efforts to connect residents to these new resources. Even better, paired with new local funding, federal relief can help DC build a just recovery that extends to all residents and an antiracist, equitable future where all can thrive.

Need for public support increased sharply in the pandemic, as residents faced unprecedented health care needs, fell behind on rent, struggled to keep their businesses afloat, and fell behind in remote learning. Among DC’s Black and brown communities, particularly women of color, this need is severe due to years of policies and practices that disadvantaged them and privileged white residents in employment, education, and wealth building opportunities. Left as is, the District’s budget will not adequately reduce this hardship and build a robust recovery: DC revenues are projected to fall by $2.3 billion, compared to pre-pandemic levels, through the 2024 fiscal year as a result of the economic downturn, making it hard to address these growing needs.[1]

It will take intentional investments and interventions to reverse course and pursue an antiracist, equitable future. In this pivotal moment, DC policymakers must spend and add to federal rescue funds in a timely way, with a laser focus on addressing the racial inequities that have excluded Black and brown communities from economic gains and left them more vulnerable to the COVID-19 crisis.[2]

The American Rescue Plan Can Help Chart a Just Recovery and Future

The American Rescue Plan offers a unique and timely opportunity to make a down payment on a just recovery in DC. The District will receive nearly $2.4 billion in flexible relief funds that can be used to respond to the heightened health and economic needs of residents due to the pandemic and its fallout. The remaining funds (at least $950 million) will go to education, child care, cash assistance, and other needs (Appendices A and B). The District must spend most of these funds over the next two to three years but can spend some funds over a longer period. This federal support comes on top of the smaller December 2020 federal relief package.

It is now up to DC to build on this aid and target it to those most in need—addressing structural inequities by race, gender, and income in ways that set up a recovery that extends to all residents and an antiracist, equitable, and inclusive future that all parts of the city deserve.

How to Use Flexible Funds to Meet Pandemic Needs

Through the ARP, DC policymakers have the flexibility needed to target these funds to residents’ most pressing needs as well as the long-term, structural issues that made the challenges so much worse for communities of color. DC’s $2.4 billion in funding comes through the ARP’s fiscal relief for states, counties, and metro areas, and it includes $755 million to make up for the amount that DC was shortchanged in the March 2020 federal CARES Act, which treated the District as a territory rather than as a state. The ARP’s flexible funds also include $107 million for capital projects—construction or other durable infrastructure—that address needs created by the pandemic and support work, education, or health monitoring. These flexible funds are available through December 31, 2024, meaning they can be used in fiscal years 2021 through 2024. However, given the urgent needs, policymakers should devote substantial resources to priority areas now rather than waiting until the end of the eligible period.

These resources will allow DC to avoid budget cuts and instead make strong and immediate investments that repair the damage of the pandemic and economic shutdown. In particular, DC policymakers must prioritize relief for the thousands of residents facing eviction, the students who have fallen behind, the residents struggling with food insecurity or mental health challenges, the child care facilities that are at risk of closing forever, and the other small businesses that may not otherwise recover. The Mayor and Council should also reverse budget cuts made early in the pandemic to mental health services and other areas.

The District should also use federal funds to address the structural challenges that have long been recognized but never fully addressed: ending homelessness and the need for deeply affordable housing, eliminating food deserts in low-income neighborhoods, providing high-quality early childhood education to all children, meeting the educational and socio-emotional needs of Black and brown youth, improving mental and physical health services, providing assistance to undocumented immigrants, and more. In doing so, DC policymakers should resist any calls to replenish reserves and consult with advocates, service providers, and members of DC’s communities to incorporate their input, expertise, and lived experience in the decision-making process.

Education Funding

The ARP offers an unprecedented opportunity to bolster our PreK3-12 schools at a time when learning loss brought on by the pandemic is compounding long-standing inequities in our school system and economy, both of which have put Black and brown children and children in low-income homes at a disadvantage. DC will receive $386 million to spend on PreK3-12 public and charter schools through 2024. At least 90 percent of these funds ($348 million) must go to DC Public Schools (DCPS) and public charter schools, and up to 10 percent can be reserved for other state-level education needs.

- Funds to DCPS and Public Charter Schools: Of the funds to DCPS and public charter schools, at least 20 percent (about $70 million) must be used to address learning loss in the pandemic, with the remainder broadly available for any other purposes allowed under federal education law.

- Funds for State-wide Functions: The ARP will allow the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) to spend no more than 10 percent of their funding on state-level initiatives to address students’ educational needs.

- Funds for Specific Purposes: OSSE must use at least five percent of its total funding to address learning loss (this is separate from the requirement for DCPS and Public Charter schools). OSSE must also use at least one percent of funds to provide summer learning opportunities and at least one percent for afterschool programs.

These federal dollars allow the city to supplement limited, local funds and give DCPS and public charter schools substantial, flexible resources to address the deep needs of students. DCPS plans to stabilize budgets for all individual schools and staff using some of its federal funds; the system should use the remaining funding to enhance investment in mental health services, technology, or basic education services.[3]

The ARP includes provisions to ensure the District does not supplant existing education spending and to protect schools with student populations that are majority low-income and of color. DC policymakers should stay true to these intentions and avoid replacing with federal funds spending that otherwise would be funded locally. The two provisions are as follows:

- The ARP requires that education spending remain the same share of overall state spending as in the average of 2017 through 2019. Between 2017 and 2019, education equaled about 21 percent of DC’s general fund budget.[4] For FY 2022, the amount that must be maintained is $2.1 billion—about the same as the FY 2021 budget for education. This means that any increase in education spending over the FY 2021 level could be funded with federal dollars. DC policymakers should layer federal dollars on top of the typical annual growth in education funding, which is roughly $100 million per year.[5]

- Protection for High-poverty Schools: The ARP prevents DCPS—or public charter schools with multiple campuses—from reducing funding for high-poverty schools on a per-pupil basis any more than the Local Education Agency (LEA)-wide reduction in per-pupil spending.[6] Because it is unlikely that DCPS or PCS will receive less funding overall per pupil, this effectively means DCPS and public charter LEAs cannot reduce per-pupil spending for high-poverty schools in FY 2022 and FY 2023.

To be true to ARP’s intent and to meet the incredible need of students facing learning loss and longstanding education inequities, the District should use the federal funds to further supplement the Mayor’s proposed 3.6 percent increase to per-student spending—which is below what the District itself deems as adequate[7]—and to protect high-poverty schools and the students most at risk of falling behind.

Early Education

Together, the ARP and the December 2020 relief package provide a down payment for stabilizing and improving DC’s early care and education systems, with a total of $82 million to support early childhood education providers and to increase access to high-quality child care.

- Support for Providers: DC will receive $40 million under ARP in “stabilization grants” for early childhood education centers and homes. Grants are available to all providers—not only those serving low-income children—and can be used to pay for staff, rent or utilities, PPE, mental health support, and more. The stabilization grants must be obligated by the end of FY 2022 and spent by the end of FY 2023. These funds are in addition to $17 million DC received (and the Mayor obligated[8]) from the December 2020 federal relief legislation to help child care providers survive the pandemic.

- Support for Subsidized Child Care: DC must also obligate $25 million in ARP funding by the end of FY 2023 and spend it by the end of FY 2024 on the child care subsidy program. This is flexible funding to enhance subsidized child care. DC and states must use these funds to supplement child care funding rather than replace local funding. The ARP also provides a permanent $1 million funding increase to the Child Care Entitlement to States for the subsidy program.

With the $82 million in fund, the District can make substantial grants to preserve the supply of child care and support early childhood education providers, who have been forced to work with both reduced capacity and reduced demand but who will become increasingly important as the economy reopens. Policymakers should allocate the stabilization grants immediately to maximize their impact.

Federal child care subsidy funding can also help DC go beyond just preserving our child care capacity to make bold systems changes, like raising wages for early childhood educators and thereby increasing access to high-quality early childhood education for families struggling on low incomes. Using these federal dollars on top of approving the Under 3 DC campaign’s request for $60 million in local funds is crucial. OSSE could also use the federal funding to pay programs participating in the child care subsidy program based on child enrollment rather than attendance. These efforts to develop a multi-year approach to supporting a strong child care system should begin right away.

The District will also receive a little more than $2 million for Head Start and just over $1 million for Individuals with Disabilities Education Act services for infants and toddlers.

Eviction Prevention, Housing, and Homelessness

The District’s already severe housing affordability crisis and struggle to end homelessness has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis. DC will receive nearly $400 million in federal relief to prevent evictions, address homelessness, and otherwise meet housing needs.

- Eviction and Utility Assistance: The District received $200 million from the December 2020 federal relief legislation and $152 million in ARP funds to prevent the evictions of residents who fell behind on their rent or utilities in the pandemic. Payments can cover up to 12 months of rental arrears and up to six months of future rent, although only three months of future rent can be awarded at a time. The December funding must be spent by September 30, 2022 and the ARP funds by September 2027.

- Homelessness Assistance: DC will receive about $19 million in HOME (homelessness assistance) funding that can be used for affordable and supportive housing development, short-term rental assistance, development of non-congregate shelters, and support services for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness, including survivors of domestic violence and veterans. Funds for direct services must be spent by September 2025 and those for administrative costs by September 2029. The Mayor announced that she plans to use at least some of the funding to buy motels or other buildings to convert into permanent affordable housing.

- Emergency Housing Vouchers: DC will also receive a portion of the $5 billion available nationally for “emergency housing vouchers,” which are rental assistance subsidies for people who are at risk of homelessness, recently homeless, or fleeing domestic violence. The funds will be distributed to the DC Housing Authority based on a national formula. The federal government may reallocate any vouchers that remain unused.

- Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program: DC will receive $14 million to help low-income residents pay outstanding utility bills. The funds must be spent by the end of 2022.

- Housing Counseling, Fair Housing, and Homeowner Assistance: The ARP will provide at least $50 million for foreclosure prevention and an unknown level of funding for housing counseling and fair housing activities. The funding for housing counseling will go directly to housing counseling intermediaries and state housing financing agencies. The fair housing funding will go directly to fair housing organizations and other nonprofits.

Together, these funds will help prevent further harm from the pandemic and help DC provide safer housing for future crises. With this funding, the District should be able to prevent evictions due to non-payment of rent in the pandemic for all or nearly all affected households. The Mayor recently launched a “Stay DC” eviction assistance program, committing all of the $352 million available for eviction assistance.[9]

While these funds can be spent over several years and for a variety of purposes, DC lawmakers should ensure that eviction prevention and energy assistance funds are spent quickly. They also must ensure that landlords receiving funds do not evict tenants and that the DC Housing Authority uses all vouchers that are made available to the District.

Assistance for Families with Children

The District will receive more than $14 million in Pandemic Emergency Assistance for families with low incomes and minor children. The funding will flow through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program but is not limited to TANF families. This assistance can last no more than four months and can be distributed as emergency housing and short-term homelessness assistance, emergency food aid, utilities payments, burial assistance, clothing allowances, and back-to-school payments. States cannot use the funds to cover the costs of providing regular monthly TANF cash assistance, which is designed to help families meet recurring and ongoing needs.

Mental Health

DC will receive nearly $3.7 million in Mental Health Block Grant funds, which can be used for new programs or to supplement current activities for adults with serious mental illness and children with serious emotional disturbances. The District will also receive nearly $5.9 million in additional Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant funds, which support alcohol and other drug abuse services, including community treatment, residential and recovery support services, and prevention and health promotion services. The funds are intended to serve pregnant women and women with dependent children, intravenous drug users, and individuals in need of early intervention services for HIV/AIDS, primary prevention services, and/or tuberculosis services.

Direct Assistance to DC Residents

The ARP includes substantial support for DC residents, especially families with children, that will help them weather this crisis and see long-term gains. Much of that assistance is short-term, but it is likely that President Biden and Democrats in Congress will work to make key components3 permanent. As is, direct assistance to Americans in the ARP will reduce poverty by up to 50 percent among families with children and could boost social mobility long-term.[12] Economic security programs such as cash assistance, food assistance, and family tax credits—which bolster income, help families afford basic needs, and keep millions of children above the poverty line—help children to do better in school and increase their earning power in their adult years.[13] These outcomes are good for children, their futures, and our economy.

Child Tax Credits: This investment in children is one of the most important elements of the new federal relief—especially if it is made permanent. The ARP makes three key policy changes and one key administrative change to the existing child tax credit:

- Increases the credit from $2,000 to $3,600 for children under age six and to $3,000 for older children.

- Covers children up through age 17—instead of age 16.

- Structures the child tax credit (CTC) so that families with low or no earnings can receive assistance, such as a parent receiving unemployment, Social Security Income, or cash assistance. Currently, only families who earn enough to owe substantial federal income taxes can fully use the child tax credit.[14]

This means that a parent living on disability income with two children could receive up to $7,200 per year. A middle-income family with two children could see their child tax credit benefits increase by up to $3,200. The changes to this tax credit will lift 4.1 million American children out of poverty, which is about $18,000 a year for a single-parent family of three.

In addition to these policy changes, the federal law requires the IRS to make payments to families on a periodic basis, rather than once a year, to help families with ongoing expenses. Families will be able to apply to receive half of their child tax credit for 2021 between July and December 2021, rather than waiting until they file their 2021 tax return next year. The IRS advance payments may be made monthly but could be less frequent if the IRS cannot get this program up and running quickly. The expanded CTC benefits to the District will be substantial:

- Overall, 94,000 children—three-fourths of all children in DC—will benefit from these changes. Of the children benefitting, 67 percent are Black, 16 percent are Latino, and nearly 11 percent are non-Latino white.

- Some 52,000 children—80 percent of whom are Black—whose families currently get no or limited benefit from the $2,000 child tax credit will benefit. These are families who lack earnings or have low earnings.

- The added benefits will lift 8,000 DC children out of poverty—fully one-third of all DC children who are poor.[15]

While this change is just for one year, President Biden has already indicated his desire to make it permanent, which would be good for children, families, and our local economy.

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC): The federal EITC provides substantial tax assistance to families with children who work but have modest earnings. The EITC is also available to workers without children in the home, but the income cap is very low—under $16,000—and the maximum credit is just $530, compared with $6,728 for families with three or more children. In addition, the federal EITC is not available to childless workers who are under age 25 or older than 65. (The DC EITC has broader eligibility rules for some workers.)

The ARP expands the EITC for tax year 2021, benefiting 33,000 low-wage workers in DC. It nearly triples the maximum EITC for childless workers to $1,500, increases the income eligibility to at least $21,000, and covers workers age 19-24 who are not full-time students and workers 65 and older.[16]

Stimulus checks: The ARP provided $1,400 to single people with incomes below $75,000 and families below $150,000. This comes on top of the $600 payments provided in December.[17]

Unemployment Assistance: Workers facing unemployment will get an additional $300 per week, on top of regular Unemployment Insurance benefits (maximum of $444 in DC) through September 2021. The ARP also suspends federal income taxes on unemployment insurance benefits up to $10,200 for those whose incomes are less than $150,000.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): The ARP extends through September 2021 the temporary 15 percent SNAP benefit increase that lawmakers previously approved through July 2021. This translates to a $29-per-month average increase for each of the 137,000 DC residents receiving SNAP benefits and a $87-per-month average increase for a family of three.[18] The ARP also increases the amount of fruits and vegetables WIC participants can obtain, which will increase the monthly value of WIC foods by 70 to 75 percent.[19] WIC provides supplemental foods to low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and non-breastfeeding postpartum women, and to infants and children up to age five.

Health: The ARP reduces what DC residents must pay for insurance premiums when they buy insurance through DC Health Link—DC’s health care exchange.

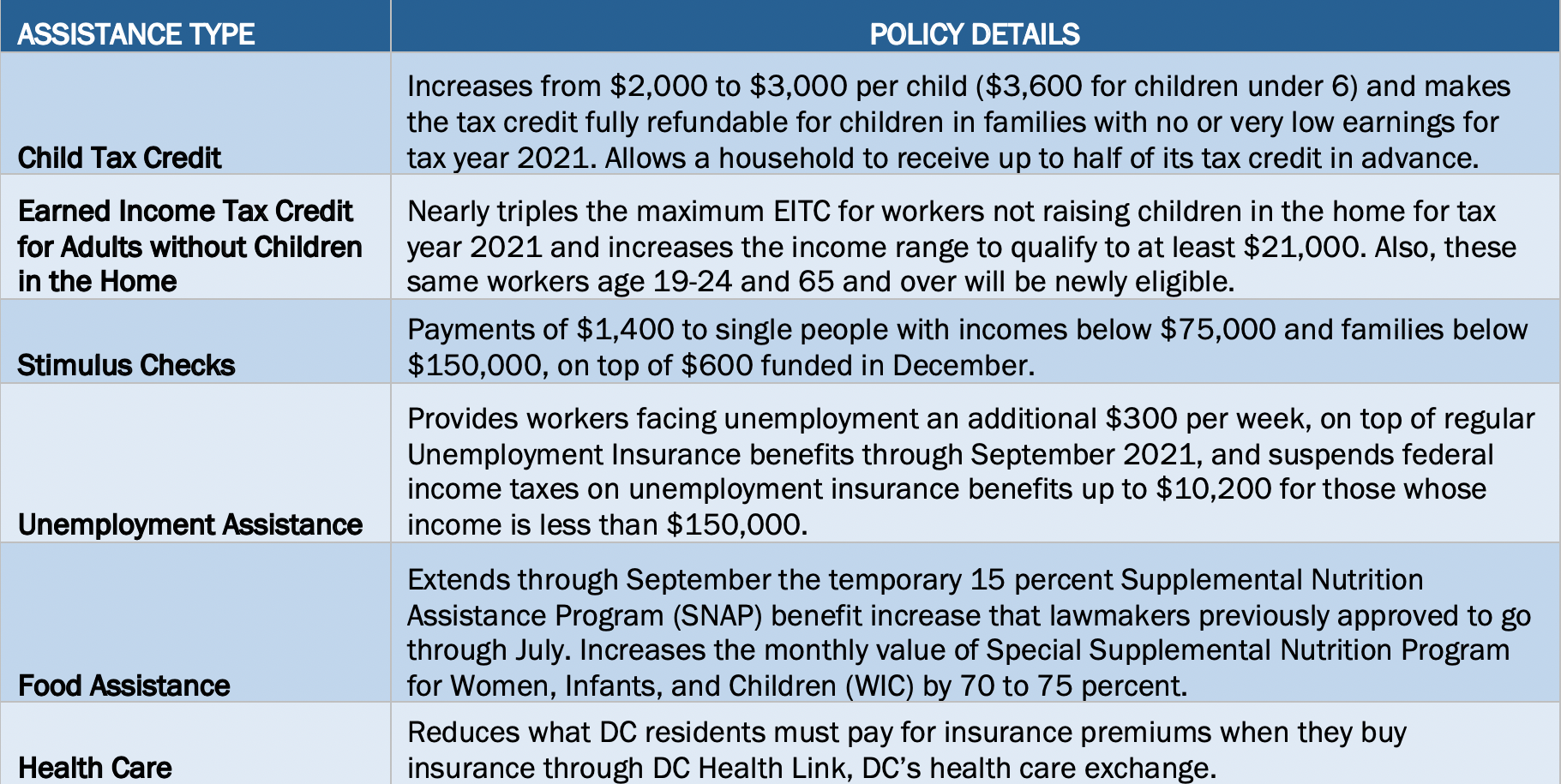

DC Policymakers Should Target, Supplement, and Connect Relief to Residents

The billions of dollars in federal relief available to DC provides an unprecedented opportunity to truly “build back better.” But to fully address and move forward from this health and economic crisis, which deepened the continued harms of the last recession, DC policymakers must target, supplement, and connect these resources to residents. To do so effectively and over the long term, we recommend the following strategies:

- Target ARP Dollars to Those Most in Need: DC policymakers should address the deep, immediate, and racial harms of the pandemic by using ARP funds to help the thousands of residents, especially Black and brown ones, facing eviction and homelessness, education losses, food insecurity, and mental health challenges. The funds will also need to reach the child care settings and other small businesses that are at risk of closing forever. The Mayor and Council also should reverse budget cuts made early in the pandemic, in mental health services and other areas.

- Promote Racial Equity by Addressing Long-Standing Inequities: The District should make investments to repair the racial harm of the pandemic, which will take years, and use federal resources for bold and creative investments to address long-standing inequities in income, wealth, jobs, education, and health. Federal funds should be used to address challenges that have long been recognized but never fully addressed: ending homelessness and the need for deeply affordable housing, eliminating food deserts in low-income neighborhoods, providing high-quality early childhood education to all children, meeting the educational and socio-emotional needs of Black and brown youth, improving mental and physical health services, providing assistance to undocumented immigrants, and more.

- Supplement and Sustain the Recovery with Local Investments: The Mayor and Council should devise a strategic spending plan that initiates long-term investments in racial and economic equity and a strong economy. This must include continuing investments when federal funds run out, to prevent any backsliding. To do so, DC policymakers should supplement federal funds through better use of reserves and raising taxes on wealthy residents. A more just tax system will support a more just and long-lasting recovery—one that addresses long-standing racial inequities in income, wealth, jobs, education, and health.

- Engage Residents in and Connect them to Relief: DC leaders must include DC residents in budget decisions, especially the Black and brown communities who stand to benefit the most, and share information on how ARP funds are spent, and why. The Mayor and DC Council should work now to share ideas and solicit input from residents, and the Council should hold a hearing, with public input, to discuss the best use of ARP funds. And to increase transparency, the Mayor should report on a regular basis—monthly for the next few years—on decisions made and spending that occurs with these funds. Extensive outreach will be critical to ensuring that these economic assistance programs reach all eligible residents, particularly among those who mistakenly believe they are not eligible or fear that participating in these programs could have negative immigration-related or other consequences.

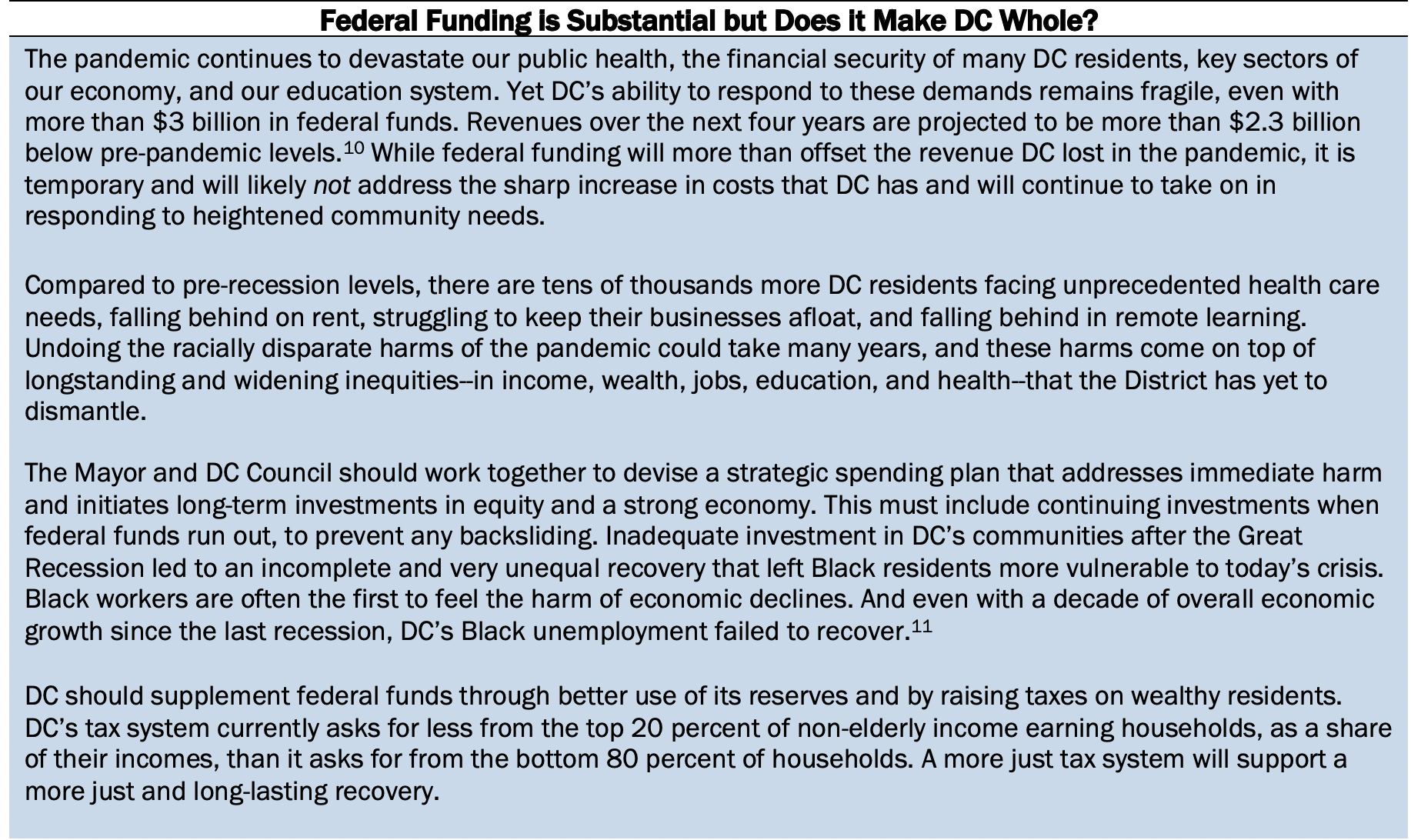

APPENDIX A: Snapshot of Core American Rescue Plan Funds Coming to DC

Direct Funding to Address Pandemic Needs and “Build Back Better”

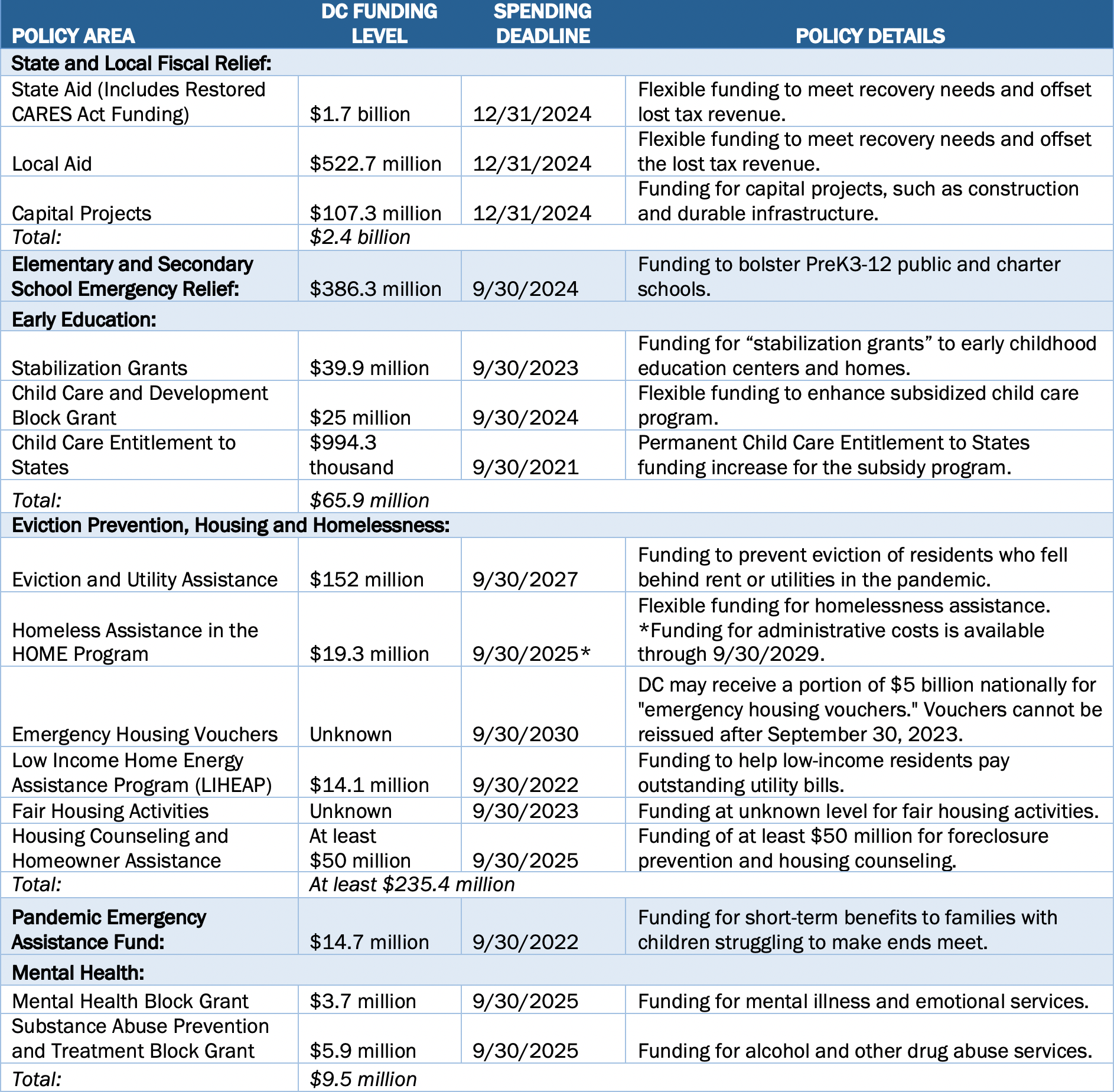

APPENDIX B: Snapshot of Core American Rescue Plan Assistance Coming to DC

Direct Assistance to DC Residents

Source: DCFPI’s analysis of the American Rescue Plan and supporting documents from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

[1] Tazra Mitchell, “DC’s Financial Challenges Remain, Even As its Budget Deficit Shrinks,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 3, 2021.

[2] Danielle Hamer, “The District Must Enact Revenue Options to Thwart Deepening Income Inequality,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, December 15, 2020.

[3] Mayor Muriel Bowser, “Mayor Bowser Announces Additional COVID-19 Recovery Investments for DC Public Schools,” Executive Office of the Mayor, April 29, 2021.

[4] This reflects OSSE, DCPS, and Public Charter School general fund spending as a share of total general fund spending.

[5] DCFPI’s analysis of the DC approved budget.

[6] The ARP defines “high-poverty” schools as the poorest 25 percent of schools within a Local Education Agency.

[7] To learn more about adequate levels and the District related adequacy study, see: Qubilah Huddleston, “DC Policymakers Must Make Bold Investments to Address Longstanding Educational Inequities,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, February 26, 2021.

[8] Executive Office of the Mayor, “Mayor Bowser Announces Over $16 Million in Financial Assistance to Sustain DC’s Child Care Sector,” March 9, 2021.

[9] Executive Office of the Mayor, “Mayor Bowser Announces $350 Million Rent and Utility Assistance Program for DC Residents,” April 12, 2021.

[10] Tazra Mitchell, “DC’s Financial Challenges Remain, Even As its Budget Deficit Shrinks,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 3, 2021.

[11] Doni Crawford, “Black Workers in the Grip of the Recession–Declining Trust Fund Could Cause More Harm,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, November 2020.

[12] Zachary Parolin et al., “The Potential Poverty Reduction Effect of President-Elect Biden’s Economic Relief Proposal,” Center on Poverty and Social Policy at Columbia University, January 14, 2021.

[13] Arloc Sherman and Tazra Mitchell, “Economic Security Programs Help Low-Income Children Succeed Over the Long-Term, Many Studies Find,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 2017.

[14] This comes from making the credit “refundable.” Under “non-refundable” credits, the credit can be used only to reduce or eliminate a household’s tax liability, with any credit amount that exceeds tax liability being forfeited. Under “refundable” credits, families with limited or no tax liability can claim the full credit, with the credit amount that exceeds tax liability sent as a refund check. Refundability is key to ensuring that low-income families can claim benefits that higher-income families claim.

[15] Chuck Marr et al., “House COVID Relief Bill Includes Critical Expansions of Child Tax Credit and EITC,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 2, 2021.

[16] Chuck Marr et al. (2021).

[17] IRS, “Questions and Answers about the Third Economic Impact Payment — Topic B: Eligibility and Calculation of the Third Payment,” Accessed April 14, 2021.

[18] See Table 1: Dottie Rosenbaum et al., “Food Assistance in American Rescue Plan Act Will Reduce Hardship, Provide Economic Stimulus,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 29, 2021.

[19] Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Implementing the American Rescue Plan,” April 16, 2021.