In the District, tens of thousands of our neighbors are out of work, going hungry, and falling behind on rent due to the recession. The pandemic has a particularly tight grip on Black people, as its devastation, in part, thrives on racial and economic inequality. As many as 72,000 workers—mostly Black—are receiving unemployment insurance (UI) benefits or awaiting approval from the DC Department of Employment Services (DOES). Unemployment benefits replace lost wages, providing crucial financial stability to unemployed workers and increasing economic activity when the economy needs it the most.

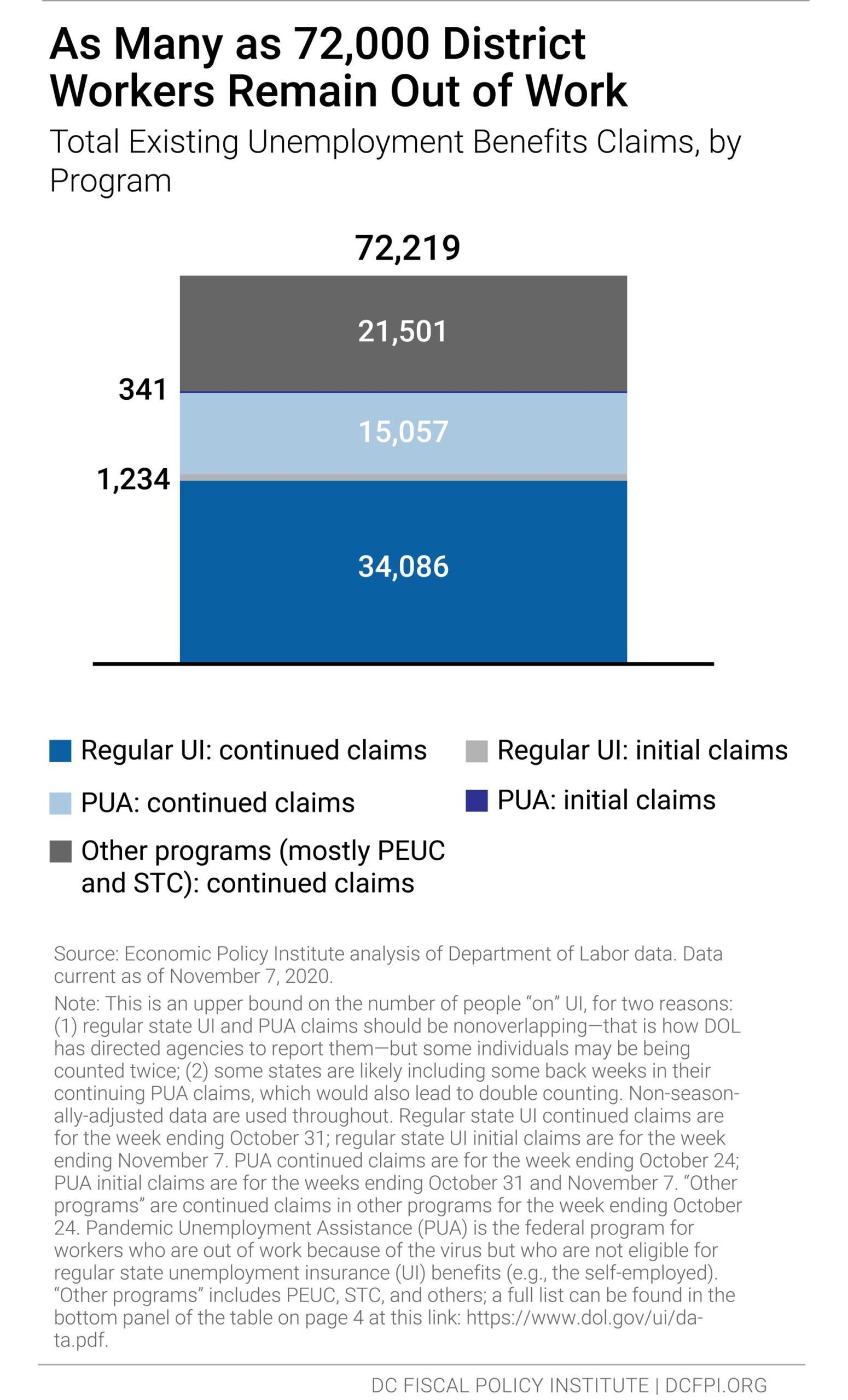

A little over half of the 72,000 workers are receiving or awaiting regular UI, with the others drawing down federally-funded benefits. Because this recession led to an unprecedented drop in the number of workers over an extended period of time, the demand for UI benefits has put the trust fund’s solvency at risk—with its balance declining from over $521 million at the beginning of the year to just over $100 million at the start of November. DC’s Chief Financial Officer will soon recommend changes to update the UI tax structure to improve its solvency, which will be followed by legislation.

Policymakers should ensure that the resulting legislation is baked in equity and designed to protect workers and provide relief to small businesses in the hardest hit industries.

Black Workers Make Up the Majority of District UI Claimants and Live in the Hardest Hit Wards

Over 155,000 claims for benefits have been filed in the District since March 13th, and the September unemployment rate is 8.7 percent, compared to 5.3 percent a year ago. The rough 72,000 workers still receiving or awaiting benefits are utilizing the range of programs and extensions available to them—from traditional UI to CARES Act programs like Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation and Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (Figure 1).

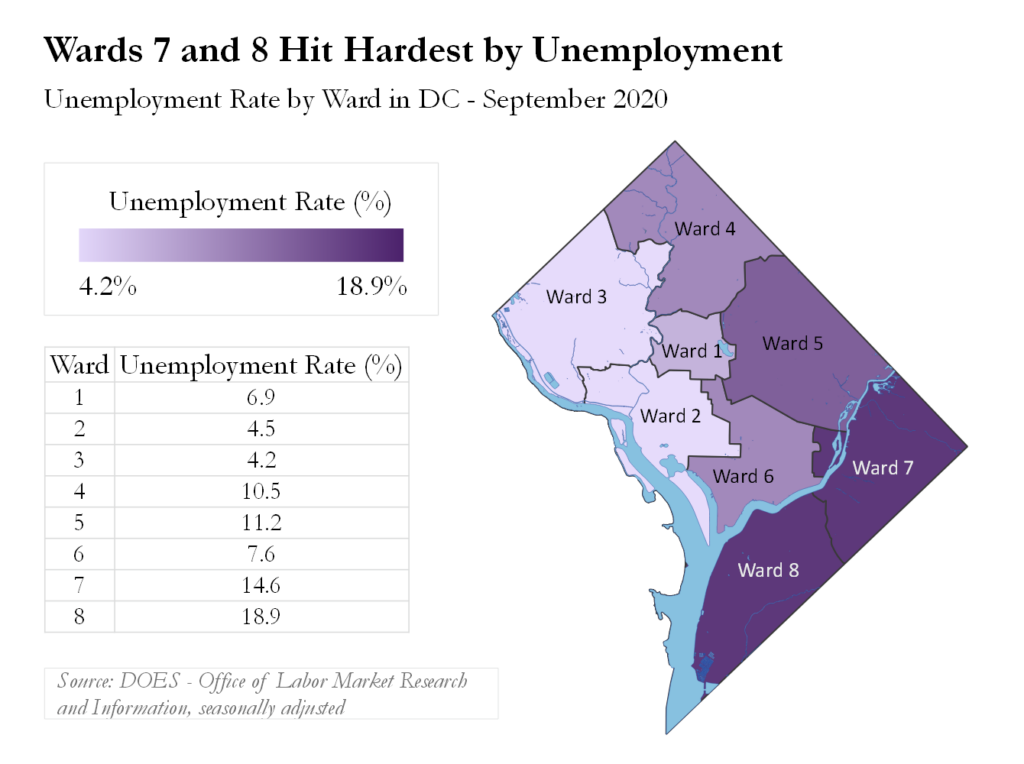

Black workers are often first to feel the harm of declines in our economy and the last ones to recover due to structural racism and a broken economic structure. Prior to the pandemic, Black unemployment levels failed to fully recover from the Great Recession. In DC, the two wards with the largest Black population have the highest rates of unemployment at 14.6 percent and 18.9 percent, respectively (Figure 2). Rates are far lower in the mostly-white Ward 3. And an average of 54 percent of UI claimants since March working in the District are Black, according to The Century Foundation’s analysis of Department of Labor data. This is a disproportionate number as Black workers make up just 36 percent of the District’s labor force.

The National Employment Law Project, in partnership with ONE DC and its Black Worker and Wellness Center, recently held its first Black Worker Listening Session on unemployment compensation and unemployment in the District. It is worth a review—you can learn from the first-hand experiences of four Black DC workers navigating unemployment and uncertainty, a racist economic structure, and their visions for the future here.

District Unemployment Insurance Fund Declines, Making Solvency a Concern

The federal-state UI system is funded through payroll taxes on employers. For the local UI tax, DC employers pay a tax rate on the first $9,000 in wages of each employee, but the tax rate varies depending on the employer’s record of collecting benefits and paying taxes, and the amount of fund reserves. For the federal UI tax, DC employers are currently paying a 0.6 percent tax rate on the first $7,000 in wages, or $42 a year per employee, but this varies based on the District’s borrowing history. The District’s UI system has a forward-funded structure, intended to build up reserves during good times to withstand tough times like the last Great Recession and this pandemic. At the start of this year, the fund balance was just over $521 million before the pandemic led it to decline to $104 million at the start of this month.

When states’ and the District’s trust funds decline, policymakers can borrow from the federal government to improve solvency and/or restructure the program, including changes to the unemployment tax and benefits. Given the severity of this pandemic, and in the absence of substantial and sustained federal relief, DC will likely have to do a mix of options both in the short and long term so that the payment of UI benefits are not interrupted.

If the District borrows money from the federal government, it will have to repay the debt, potentially in the form of a federal unemployment insurance credit reduction that increases the federal UI taxes that employers pay. Or, the District could restructure the UI tax in a way that brings in more revenue to pay down the debt and build back a healthy reserve so we’re ready for the next economic downturn—possibly by asking employers with higher wage employees to pay more of a fair share. When considering changes to UI, District policymakers should consider solutions that protect workers and the industries and employers hit hardest, including not cutting the amount nor duration of benefits for workers.