This report is supported by grants from the Abell Foundation and The Partnership to End Homelessness, an impact initiative of the Greater Washington Community Foundation.

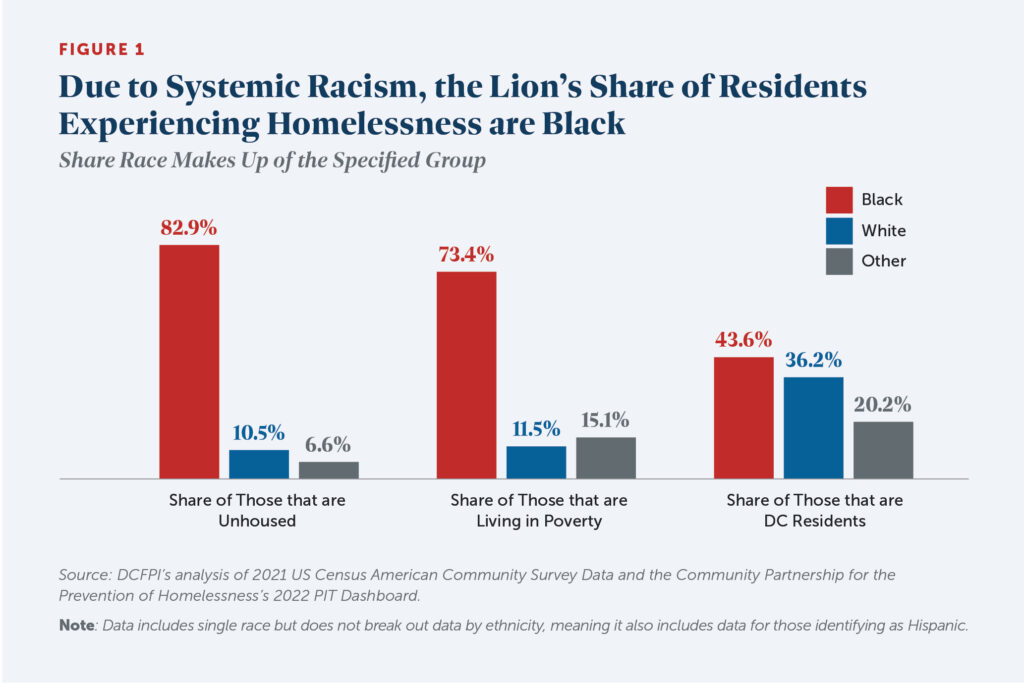

Every person deserves the dignity of a home. Yet, with 65.8 persons experiencing homelessness per every 10,000 residents, DC has one of the highest rates of homelessness in the country, and nearly half of individuals that are unhoused are experiencing “chronic homelessness.”[1] Chronic homelessness is the condition of being homeless for a year or more, or repeatedly, while struggling with a disabling condition such as a serious physical and mental illness. In DC, nearly 83 percent of individuals experiencing homelessness are also Black.[2]

At the root of homelessness in the District are high housing costs and the structural racism that has created disparities in housing, wealth, incarceration, and health. Generations of federal and local policies and practices have blocked Black households from equitable access to employment, income, and housing, leaving Black residents of DC less likely to own a home and more likely to rent in a market with extreme and rising costs.[3] Black residents are also more likely to experience risk factors for homelessness, such as poverty, incarceration, foster care, and pre-existing medical and behavioral health conditions that interfere with maintaining a job and social ties.

Ending chronic homelessness—or reaching “functional zero” when DC has the resources and ability to house all those experiencing homelessness in any given month—would be a key step in repairing one of the deepest harms of centuries of structural racism and discrimination. DC committed to doing so in Homeward DC 2.0, its fiscal years (FYs) 2021-2025 Strategic Plan to End Homelessness, and the single most important step the District laid out in that plan is to expand the Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) program. PSH combines rental assistance with supportive services for an unrestricted period, with most participants exiting the program when they pass away. While District leaders have made major recent investments in PSH (Appendix 2), leaders and providers must do more to put DC on the path to ending chronic homelessness and address implementation challenges that threaten progress.

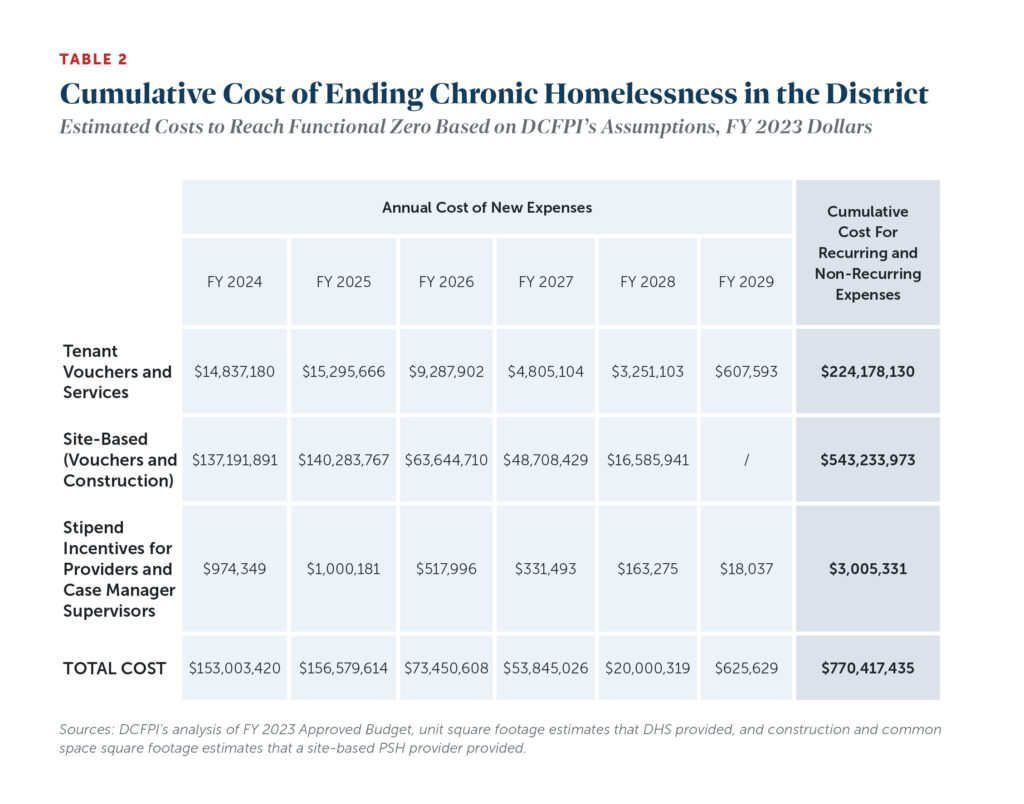

Cumulatively, it will cost more than $770 million to end chronic homelessness and reach functional zero in DC by 2030, at which point turnover from existing PSH vouchers is projected to meet the need of those newly experiencing homelessness, according to the DC Fiscal Policy Institute’s (DCFPI) projections (informed largely by Homeward DC 2.0).[4] DCFPI’s estimate reflects the costs associated with PSH site-based and tenant-based services to both end chronic homelessness and address new inflow of residents needing PSH, including vouchers, construction costs, and incentive stipends for providers. The estimate does not include land costs, which can vary greatly, and nor does it account for the proposed policy and program improvements recommended below.

Between summer and fall of 2022, DCFPI held eight focus groups of individuals who previously experienced or are currently experiencing homelessness, peer educators, PSH case managers and other experts in DC to seek their insight on program and policy improvements that they suggest the District implement. (Appendix 1). Findings that emerged from the focus groups and interviews include:

- It can take months to move into housing after receiving a voucher, and that burden is prolonging hardship for individuals, leaving them in shelter or on the streets for far too long. Extensive delays undermine their mental well-being and trust in the homelessness system.

- There is wide variability in the quality of case management that PSH participants receive, and it is common for a lack of coordination among outreach, day service, and shelter workers to disrupt participants’ ability to receive the supports they need. On the other hand, case managers report that they need more training so they can better foster healthy, supportive relationships with their assigned participants.

- Many people with lived experience are hesitant to move into site-based PSH where most or all of the apartments in a building are PSH and case managers work on site. They worry that these buildings will be chaotic like shelter and have too many rules.

- Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) housing and services are falling short, leading to homelessness and leaving individuals experiencing homelessness or living in PSH without quality care.

- More older adults are experiencing homelessness, but they have complex needs that are not met by current homeless services.

DCFPI used this input to develop recommendations for DC policymakers, which include:

- Speeding up the leasing process by launching a 100-day bootcamp to identify and solve problems, ensuring DCHA conducts inspections promptly, and providing transportation so clients can view units quickly.

- Increasing the supply of case managers and strengthening case management, by improving training, coordination between PSH case managers and day program, outreach, and shelter case managers. The Department of Human Services and providers should work together to provide peer learning opportunities. Information sharing with clients also needs improvement.

- Soliciting client feedback on the design of PSH sites to ensure the sites address their needs and concerns. Mandating training to property management staff who interact with clients and help develop and implement building rules.

- Expanding and strengthening DBH’s housing programs to clients so they don’t have to first become homeless and then wait for PSH housing, increasing the number of psychiatric beds, and providing services to residents with traumatic brain injuries.

- Exploring whether the District can address the concerns that nursing homes and assisted living facilities raised about accepting individuals experiencing homelessness. If not, the District will need to create dedicated facilities for individuals experiencing homelessness and ensure those facilities meet client needs.

Ensuring that every person has access to safe, decent, affordable housing, regardless of race, would correct one of the most fundamental racial injustices in the District and the nation’s history. As DC fulfills its commitment to end chronic homelessness, strategies should be grounded in the framework that interventions will be most successful when informed by residents who are experiencing or have experienced homelessness. And, while not the focus of this report, it must also be said that preventing individuals from becoming homeless in the first place is a key strategy in ending chronic homelessness. The District should engage in upstream prevention efforts to stem the flow of people into homelessness, particularly in the criminal justice, child welfare, behavioral health, and health care systems that feed the problem.

Table of Contents

- Ending Chronic Homelessness is a Matter of Racial Justice

- Permanent Supportive Housing Is the Key to Ending Chronic Homelessness

- Cost of Ending Chronic Homelessness

- Ensuring Success: Lessons from Lived Experiences of Unhoused Residents and from Case Managers

- Appendix 1: Focus Group Questions

- Appendix 2: Recent Positive Developments Put DC in Striking Distance of Ending Chronic Homelessness

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines a person as chronically homeless if they have a disability and have been homeless for more than a year or have had four or more periods of homelessness in the past three years that total at least one year.[5] Individuals who meet these criteria and have been staying in an institutional care facility, such as a jail or hospital, for fewer than 90 days are also considered chronically homeless.[6]

Individuals who are chronically homeless have a harder time recovering and finding housing, regardless of what pushed them into homelessness, compared to all people who are unhoused, according to the National Alliance to End Homelessness. They are likelier to face extended and repeated periods of homelessness.[7] Preventing chronic homelessness is particularly important as the longer people are homeless, the more their circumstances worsen, including health, access to jobs, and support networks.[8] The longer people must wait for help, “the more intensive—and expensive—the intervention needed will be.”[9] This group is most in need of both housing and supportive services to see long-term improvement and stability.

In FY 2022, 7,834 individuals experienced homelessness in DC, a nearly 6 percent reduction from FY 2021 and a 30 percent reduction since FY 2016, when DC’s Interagency Council on Homelessness (ICH) published its first strategic plan to end homelessness.[10] On the other hand, DC saw a dramatic increase in the number of individuals newly pushed into homelessness, to 3,989 in FY 2022 from 2,340 in FY 2021, or by 70 percent.[11] While this is a decrease compared to FY 2016, it demonstrates that the District needs to make more robust investments in homelessness prevention.[12]

The percentage of individuals experiencing chronic homelessness also decreased, according to data gathered at the annual Point in Time (PIT), the effort to get an accurate snapshot of people experiencing homelessness in DC on a single night in January. The 2022 PIT found 44 percent of individuals counted were chronically homeless, down from just over 50 percent in January 2021.[13] The District attributes this decrease to the large increase in PSH vouchers and the creation of the Pandemic Emergency Program for Medically Vulnerable Individuals (PEP-V) program, which shelters individuals in hotel rooms and provides services to help residents lease up.[14]

Ending Chronic Homelessness is a Matter of Racial Justice

Ending chronic homelessness in the District would be a key step in repairing a deep harm caused by centuries of structural racism and discrimination. Generations of policies and practices created longstanding racial inequities in housing and wealth, employment and income, education, and health care that shape the extremely racially disparate composition of the District’s unhoused population.

DC’s Black Codes, laws originating in 1808 that barred Black people from federal employment, and other pervasive labor market discrimination of the past, have combined to lock in a greater likelihood of poverty and hardship and kept Black residents and other non-Black residents of color from living to their fullest.[15] Government-sanctioned practices, such as racist zoning policies, residential segregation, redlining, restrictive covenants, and other racist practices, widened the racial wealth gap created at the outset by African enslavement. These intentional efforts to oppress Black people have left Black and brown residents of the District less likely to own a home and more likely to rent in a market with extreme and rising costs, with fewer resources to keep from falling behind on rent and facing eviction, and with fewer protections against the risk factors contributing to homelessness.[16]

Racism, of course, is not a thing of the past and continues to shape systems, policies, and practices. Black people continue to face discrimination in the labor market, including when it comes to hiring, salary, and job loss during economic downturns, as is documented by research.[17] Despite a low overall unemployment rate in the District today, the Black unemployment rate is one of the highest in the nation while the white unemployment rate is one of the lowest. This contributes to disparities in incomes: Black households have one-third the income of white households, and Black people make up the large majority of those living below the poverty line in DC.[18]

The unemployment insurance program adopted through the Social Security Act of 1935 left most Black workers ineligible at the time and continues to limit its use for many Black and brown people, and women, today.[19] That’s because it excludes many workers, like immigrants who are undocumented, people working in the cash economy, and those who have too little in wages to qualify, among others. One of DC’s major cash transfer programs—the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)—is predicated on work and primarily goes to families with children, thus excluding many Black and brown residents facing steep barriers to employment and earnings. In addition, TANF is limited in size and reach, and despite the District’s removal of time limits and certain family sanctions, its design is rooted in anti-Black racism painting Black mothers as unworthy of public supports.[20] Additionally, while federal and local housing policies are no longer explicitly racist, real estate agents—including in the District—continue to deny Black and Latinx homebuyers the opportunity to buy in neighborhoods where homeowners more easily build equity and have access to better schools.[21]

These policies and practices cause inequities to pile up, contributing to a homelessness crisis that disproportionately harms Black residents. Today, nearly 83 percent of individuals experiencing homelessness in the District are Black, even though Black residents make up only 44 percent of the District’s population and 73 percent of residents living below the poverty line (Figure 1). [22], [23], [24] This means that if DC were to reduce homelessness for Black residents and improve the homelessness system with them in mind, it would reduce homelessness and improve services for everyone.

Factors that Increase Risk of Homelessness Also Reflect Racism

Because of racism, Black residents are more likely to face many of the life experiences and factors that increase the risk of homelessness.[25] Poverty is a major factor and, in the District, Black residents are five times as likely as white residents to live on incomes that fall below the poverty line, leaving them more vulnerable to economic and health shocks.[26] Many other factors can play a role. For example, in-depth assessments of DC individuals experiencing homelessness found that 57 percent had been involved with the carceral system, and of those who had been incarcerated, 55 percent reported that incarceration had caused their homelessness.[27] More than 90 percent of DC’s incarcerated residents are Black, and nearly 96 percent of DC’s returning citizens are Black.[28] Huge racial disparities in police interactions, arrest, and sentencing greatly contribute to this overrepresentation and result from both officer discretion and formal policies.[29] Using discretion, officers are more likely to stop Black drivers and, once stopped, more likely to search Black drivers. And “stop and frisk” policies, in which officers search individuals for contraband, are most often implemented in Black neighborhoods against Black residents. This racially disparate treatment stems from the racist roots of policing, which links back to slave patrols—organizations of white men paid to capture Black people who fled enslavement and who used terror and violence to deter revolt and exert control on plantations. New forms of policing and control of Black people emerged after the Civil War, such as through enforcement of the aforementioned Black Codes, convict-leasing, Jim Crow laws, and mass incarceration, among others.[30]

Foster care involvement is also a risk factor for becoming homeless and reflects systemic racism. Many young residents who enter homelessness do so after exiting foster care. Fifteen percent of unhoused individuals in DC surveyed in 2019 reported foster care involvement, while only 2.6 percent of American adults have ever been in foster care.[31] Black children are pushed disproportionately into the child welfare system in the District, comprising 83.5 percent of children in foster care, while they comprise 54 percent of the child population in DC.[32] Disparities at every level of the child welfare system suggest that racial bias may play a role in disproportionate reporting, investigation, and child removal for families of color, and particularly Black families.[33] In addition, Black children spend more time in foster care, are less likely to be reunited with their families, and are less likely to receive services.[34]

People with pre-existing medical and behavioral health conditions are also more likely to become homeless, at least in part because inadequate treatment of these conditions can interfere with employment and disrupt social ties.[35], [36] Black individuals are less likely to get the care they need because of historic and ongoing racism. Research has found that health care professionals (especially those who are non-Black) are less likely to offer Black patients the same treatments they would offer white patients, more likely to dismiss the health concerns or level of pain of Black patients, and more likely to misdiagnose Black patients (or not diagnose them at all).[37] It can become a vicious cycle as homelessness can worsen the health conditions that contributed to an individual becoming homeless in the first place, and put appropriate care further out of reach.[38]

Rate of Homelessness Driven by Lack of Affordable Housing

While factors such as behavioral health problems or criminal justice involvement contribute to an individual’s likelihood of experiencing homelessness, a community’s rate of homelessness is driven by housing market conditions such as scarcity of affordable housing and cost of rental housing.[39] [40] A Government Accountability Office report found that every $100 increase in median rent is associated with a 9 percent increase in the homelessness rate. [41] For example, West Virginia has one of the highest rates of mental illness in the country but has one of the lowest rates of homelessness because rents are comparatively low.[42] DC has one of the highest rates of homelessness because of its very expensive rental housing, the significant gap between wages and rent, and low apartment vacancy rates.[43]

As outlined in Homeward DC 2.0, homelessness is a symptom of a much larger problem of housing insecurity and inequity.[44] In the District, there are 39,500 renter households that earn less than 30 percent of the median family income ($29,900 for an individual), who make up the largest group of households that pay more than 50 percent of their income in rent and are at high risk of losing their housing.[45] [46] In 2020, 35 percent of Black renters, 26 percent of Latinx renters, and 23 percent of Asian renters were severely cost burdened compared to only 13 percent of white renters.[47] As noted above, also at risk are the many households that are living in severely overcrowded or substandard conditions. All of them are a job loss, divorce, or a health care crisis away from being unhoused, and if they do lose their housing, some will become chronically homeless.

While not technically considered homeless, too many District residents are also doubled up, living in friend or family households because they can’t afford housing. DC had the highest number of doubled up residents per 10,000 of all states in 2019 according to a recent study.[48] While the study does not disaggregate state-level data by race and ethnicity, it shows that nationally American Indian and Alaskan Natives, Latinx, and Black people, and those who were categorized as “other race” were most likely to be doubled up.

| Homeward DC 2.0: The District’s Strategic Plan to End Homelessness |

Homeward DC 2.0 is the District’s five-year strategic plan to end homelessness, covering FYs 2021 through 2025. It models inflow into the homeless services system, outlines housing needs, and describes needed strategies. It is the work of DC’s Interagency Council on Homelessness (ICH), the body of government agencies, service providers, advocates, and residents who have experienced homelessness that guides strategies and policies for meeting the needs of residents experiencing homeless or at imminent risk of experiencing homelessness.[49] The plan lays out the District’s commitment to making homelessness:

Because the rate of homelessness is fluid, with individuals entering and exiting homelessness all the time, national expert Community Solutions developed the concept of “functional zero” as a means to measure whether homelessness is rare and brief. Functional zero means the number of individuals experiencing homelessness is equal to or lower than the average number of individuals who exit homelessness in a month.[51] For example, if the District can house 100 individuals in a month, it will reach functional zero when 100 or fewer individuals are experiencing homelessness. To achieve functional zero for chronic homelessness, the District would have to have either:

With budget investments in FYs 2024 through FY 2029 under the projections modeled in this report and the policy and program improvements outlined below, the District can meet functional zero. To monitor whether homelessness is non-recurring, the ICH currently reviews data on the number of households who return to homeless services after being housed. ICH should set a benchmark to measure whether the District is meeting this goal, with the data broken out for those facing chronic homelessness. |

Permanent Supportive Housing Is the Key to Ending Chronic Homelessness

Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH)—a nationally recognized best practice—is DC’s key program for ending chronic homelessness.[54] PSH combines a non-time limited rental subsidy with intensive, individualized, voluntary wrap around services. The Department of Human Services (DHS) contracts with outside providers to deliver PSH services, and clients can choose any provider with open case management slots. The provider then assigns a case manager to the client. The DC Housing Authority (DCHA) issues PSH vouchers, inspects apartments, and pays landlords. Generally, individuals in the program are required to pay 30 percent of their income towards rent.

PSH in the District uses a Housing First approach, offering immediate access to housing without requirements such as having income, completing mental health treatment, achieving sobriety, or taking prescribed medication.[55] Housing serves as the foundation for pursuing goals and improving one’s quality of life.[56] It is grounded in the belief that individuals need basic necessities before they can address their other needs.[57] A substantial and growing evidence base finds that individuals access housing more quickly and are more likely to stay housed under the Housing First approach.[58]

Most PSH in the District is tenant-based, meaning the client receives a voucher that they can use to rent any qualifying unit, and the voucher is attached to and moves with the client. Case managers are not onsite except to visit the client.

Homeward DC 2.0 calls for more site-based PSH, where 100 percent of the units in the building are PSH, and depending on the size of the building, the program typically provides a more intensive level of services and supports.[59] Case managers work onsite and site-based PSH must provide 24-hour front desk or security guard presence. The voucher is attached to the unit, and if the client moves, they move without the voucher.

To reduce the spread of COVID-19, the District launched the Pandemic Emergency Program for Medically Vulnerable Individuals (PEP-V). This program shelters individuals in hotel rooms, provides meals, and has onsite medical and behavioral health services. Many clients who have struggled in shelter or in their own housing have flourished in this program. While Mayor Bowser is resourcing a gradual phase-down of PEP-V as federal funding ends in May, the ICH has proposed a new PSH model, “PSH Plus.” [60] This site-based PSH would offer more intensive services for more vulnerable individuals who need additional medical and/or behavioral health services delivered on site.[61] Buildings would be particularly designed to meet the needs of this population, incorporating accessibility and trauma-informed design principles. For example, buildings would have quieter elevator equipment as individuals with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are often sensitive to loud noises, and hallways with open sight lines so that individuals feel safer and less like they are being trapped or crowded.[62] [63] The building could also offer at least one meal per day. A PEP-V medical staff person interviewed for this report noted that meals provided have improved the health of her clients.[64] Lawmakers have not yet committed to investing in PSH Plus.

PEP-V and Other Programs Offer Bridge to PSH

PSH is the primary housing solution to end chronic homelessness, but other programs play a critical role in helping some individuals avoid homelessness and helping others while they experience homelessness.

Individuals need a place to stay while they work to regain housing. A stable place to stay helps them focus on the housing process and enables PSH case managers to quickly locate individuals. Shelters are intended to be a “safe, stable” place to stay from which people can work to access permanent housing, but some of the District’s current shelters fall short.[65] While DC is in the process of replacing or rebuilding most of the shelters for individuals, existing shelters are old, dilapidated, and chaotic. PEP-V has played a crucial role in sheltering medically vulnerable individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic but are now slated for closure. DC also recently launched bridge housing—shared apartments for individuals who are in the housing process and with fewer rules than PEP-V. Many individuals who have avoided shelters in the past are relying on PEP-V and bridge housing.

Shelter case managers are responsible for assessing clients for housing and adding them to the “By Name List” of individuals experiencing homelessness used to fill open PSH slots.[66] But in reality, there are not enough shelter case managers to meet the need. Some individuals choose to attend publicly or privately funded day programs in order to access needed case management services as well as food and clothing. The District also contracts with service providers for outreach workers who provide case management to individuals living outside.

Another key strategy is helping individuals who fall into homelessness secure housing quickly, so they do not become chronically homeless. Project Reconnect helps newly homeless individuals find alternatives to shelter, such as reuniting with friends and family.

Case Management

PSH case managers primarily help participants meet three major goals 1) obtaining long-term housing, 2) maintaining their housing by complying with lease provisions and local laws, and 3) achieving the highest level of participant-driven goals possible and improve the overall quality of their lives.[67] Case managers do this through their visits and by connecting participants to other services. These goals are laid out in an Individualized Service Plan (ISP) and case managers review progress towards the ISP goals with clients every 90 days. DHS names case managers as “the most critical factor in the successful delivery of…services to the participant and supporting the participant’s lease-up to a housing unit and housing tenancy.”[68]

The District can now charge Medicaid for many PSH services, which were previously 100 percent locally funded. Medicaid is a cost-sharing health program between states, including the District, and the federal government. Because of the federal public health emergency, this year for every dollar of local Medicaid spending, the federal government will contribute $3.20.[69] In subsequent years, the District will receive $2.33 for every dollar it spends.[70] Well over 80 percent of DC residents eligible to receive PSH services are also eligible for Medicaid, and thus eligible to have Medicaid pay for their housing-related services. The District will continue to use local funds to pay for services for individuals who do not qualify for Medicaid, such as recent immigrants.

As part of the shift to Medicaid funding, the District has standardized PSH case management. There are now two phases of PSH case management, regardless of whether the participant has a tenant- or site-based voucher. The first phase is housing navigation, which includes services that help a participant find housing, if not site-based, and move into that housing. The second is housing stabilization, with services that help participants sustain this housing.[71] During the housing navigation phase, case managers help individuals locate housing, gather documents for their PSH application and their housing applications, and move in. During the housing stabilization phase, case managers help clients identify behaviors that might jeopardize their lease such as excessive noise and provide training on being good tenants. Case managers also help clients apply for and maintain benefits and connect with resources in the community, such as food banks. And finally, case managers help clients identify and pursue life goals such as improving health or rebuilding social and community connections.

While case management is voluntary, most clients allow case managers to conduct visits. For providers to be reimbursed for their services during the navigation phase, case managers must have weekly contact with clients, with two of these contacts being in person each month. For the housing stabilization phase, case managers must meet biweekly with clients, with one in person meeting per month. Case managers are also expected to accompany clients, if needed, to health and mental health provider appointments.[72] DHS sometimes requires case managers to make more visits with clients in crisis, or when there are medical health concerns.[73]

In tenant-based PSH, case managers are generally only onsite for pre-arranged visits with clients or to troubleshoot problems with landlords and property managers. In site-based PSH, case managers work onsite, allowing them to see clients around the building as well as during pre-arranged visits. In many site-based programs, clients can also drop in to see a case manager without an appointment to troubleshoot problems, rather than having to arrange and wait for an appointment. Even with the benefits, as detailed below, some individuals with lived experience perceive that site-based PSH allows case managers to more closely monitor them and interfere in their day-to-day lives. Efforts to build trust between participants, case workers, and the government remains a vital step towards ending chronic homelessness.

Clients can refuse PSH case management and instead receive only quarterly check-ins from DHS. The ICH, DHS, and lawmakers should continue to monitor this process to ensure clients who have been removed from case management are not just being removed because they are harder to serve.

Cost of Ending Chronic Homelessness

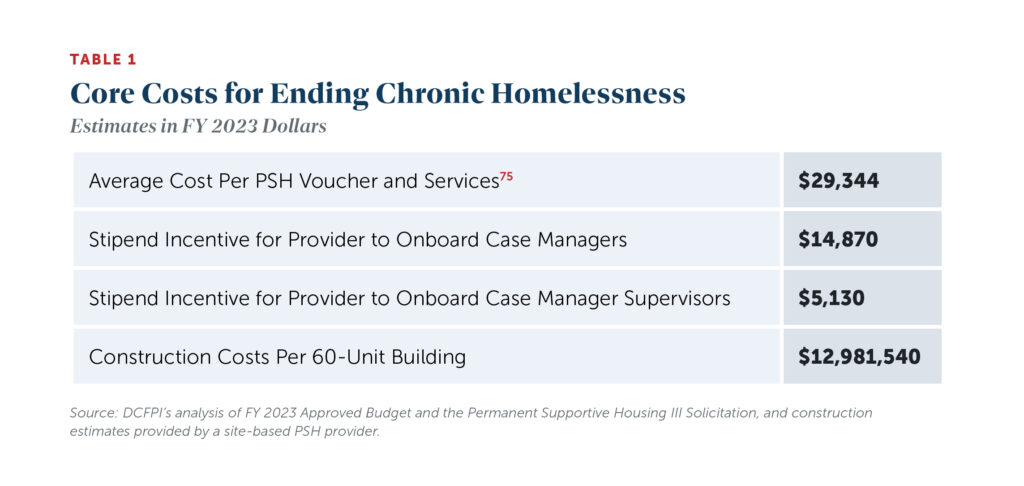

Cumulatively, it will cost the District more than $770 million to end chronic homelessness by 2030. At that point, turnover from existing PSH is projected to meet the need of those newly experiencing homelessness, according to DCFPI’s assumptions and projections which were informed largely by Homeward DC 2.0. DCFPI’s estimate reflects the cumulative costs associated with PSH site-based and tenant-based services to both end chronic homelessness and address new inflow of residents needing PSH immediately, including vouchers, construction costs, and incentive stipends for providers (Table 1). Nearly 47 percent of the cumulative cost is driven by new construction expenses for building inventory to meet current need and projected inflow. The estimate does not include land costs, which vary greatly, nor does it account for the proposed policy and program improvements recommended below. It is also beyond the scope of this paper to estimate indirect savings associated with ending chronic homelessness, although other research points to the potential for sizeable indirect savings through reductions in emergency service use, arrests, and incarceration.[74]

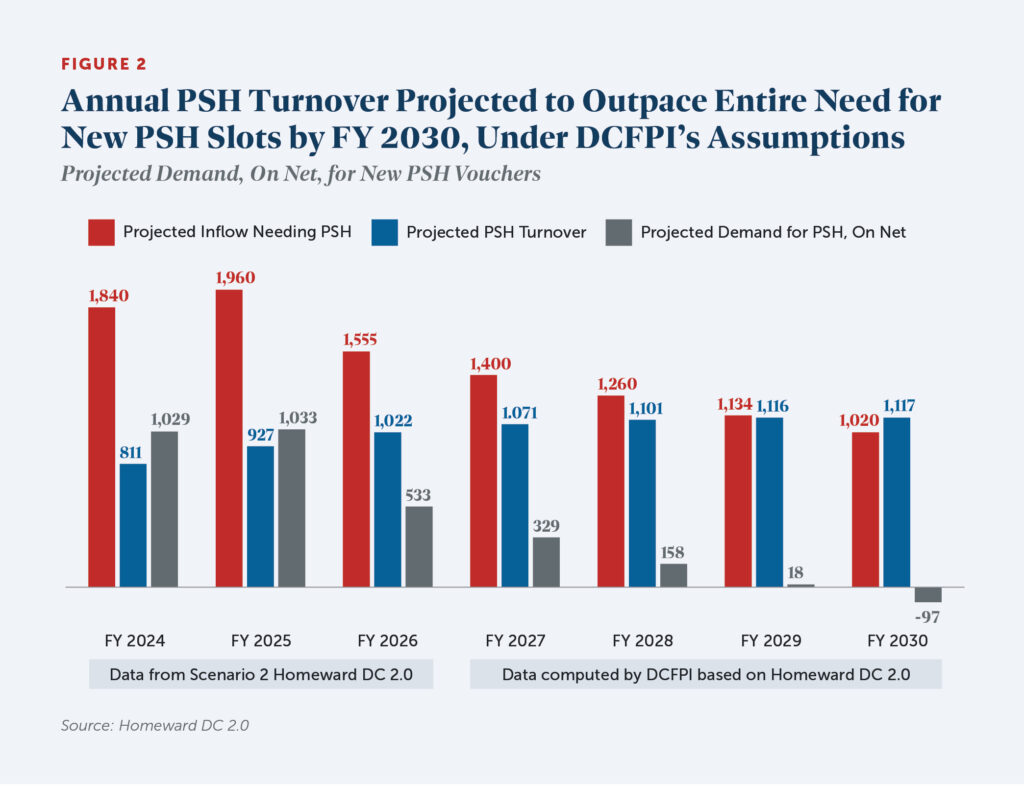

DCFPI estimates the number of additional PSH vouchers needed to end homelessness until the system is projected to reach functional zero in FY 2030 and calculates the cost of providing a PSH slot to everyone in need each year. DCFPI uses Homeward DC 2.0’s projected need for PSH vouchers in FY 2024 and FY 2025, at which point the plan ends.[76] Because individuals are entering DC’s homelessness system—and into chronic homelessness—faster than the District has been able to help them exit, additional investments are needed after FY 2025 to address new inflow until it is outpaced by natural turnover in the system to reach functional zero. For subsequent years, DCFPI projects the number of individuals expected to become homeless who will need PSH services, factoring in the strategic plan’s assumptions on inflow and turnover rates for PSH services, and then estimates the cost associated with new PSH slots through 2030.

Specifically, one scenario in Homeward DC 2.0 predicts that with extensive prevention efforts in “feeder” systems such as the criminal justice, behavioral health, and child welfare systems, the District can reduce the number of individuals becoming homeless by 10 percent annually beginning in FY 2023. However, COVID-19 and capacity challenges have delayed DC’s ability to make progress on upstream prevention. This analysis assumes that these efforts would take a few years to implement, thus keeps inflow projections flat at an annual average of 6,400 people for FY 2023 through FY 2025 and factors in reduced inflow starting in FY 2026. DCFPI also factors in Homeward DC 2.0’s estimate that only 27 percent of those entering the homelessness system need PSH and accounts for natural turnover in PSH slots that can meet part of the annual need. Approximately 9.2 percent of PSH units turn over each year, and as the District adds new PSH slots, the number turning over also increases. Most of this turnover is from client death, leaving vouchers that can be reassigned to others in need. Taken together, annual turnover would outpace the entire new need for PSH slots by FY 2030, meaning investments in additional PSH vouchers would not be necessary that fiscal year to maintain an end to chronic homelessness, assuming all else is held equal (Figure 2).

DCFPI calculates the inflation-adjusted cumulative cost for providing everyone in need a voucher until the system is projected to reach functional zero in FY 2030. DCFPI assumes that the new slots would be roughly evenly split between tenant-based and site-based units except in FY 2029 when we assumed that 100 percent of slots will be tenant-based given low projected need.[77] Site based units are combined into groups of 60 with the assumption that each building has 60 units. [78] [79] In FY 2023, the average cost of a voucher for both tenant- and site-based is approximately $29,300. Additionally, the District provides an onboarding stipend for case managers of $14,870 to both tenant- and site-based providers for every 17 new individuals added to caseload and an onboarding stipend for case manager supervisors of $5,130 for every 125 new individuals added to their caseload. Our analysis assumes the District will keep these stipends in place and allow them to grow with inflation.

Site-based vouchers carry additional construction costs. The DC Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) is allowing maximum costs for new construction to average $429 per square foot.[80] While site-based projects can be any size, the requirement for 24-hour security means that it is difficult for smaller buildings to keep operating costs within the $9,100 per unit per year limit set by DHCD. DCFPI’s analysis assumes buildings have at least 60 units to reach economic feasibility and that one-bedroom PSH units are 471 square feet each, the minimum size of the most recently constructed site-based project (The Ethel).[81] Lobby and program space can also vary greatly by project. DCFPI’s analysis assumes a minimum 2,000 square feet for lobby and program space for each new building.[82] Taken together, DCFPI estimates that a newly constructed 60-unit building will cost nearly $13 million in one-time construction funds in FY 2023.

With each passing year, the District will shrink new spending on vouchers and construction as it makes progress towards functional zero under DCFPI’s assumptions. Annual new costs will range from $153 million in FY 2024 to $626,000 in FY 2029. There will be a savings of $3.3 million in FY 2030 when turnover vouchers will more than meet the needs of individuals becoming homeless. And DCFPI estimates the cumulative cost for these recurring and non-recurring expense at $770.4 million through FY 2029 (Table 2).

It is beyond the scope of this analysis to estimate land costs for site-based projects, which can vary greatly depending on the location. Focus group participants with lived experience reported that location and public transportation access were top considerations when considering living in site-based PSH. As such, minimizing costs should not be the only consideration when choosing sites. The District can also reduce land costs by using land it already owns or leveraging land owned by nonprofit institutions. For example, the Mayor has recently launched an initiative to help faith communities build affordable housing on their land and should continue to pursue such efforts.[83]

Rising rents, inadequate eviction prevention assistance, inadequate or delayed investments in new vouchers, and continued implementation challenges related to the low supply of case workers (described below) are just a few of the factors that could keep DC from reaching functional zero by FY 2030.

Medicaid Savings

With Medicaid newly covering many PSH services, the District stands to save approximately $11 million annually starting this year. Previously, DC paid an annual average of $6,432 in local funding per person. With the shift to Medicaid coverage of PSH services, providers will receive about $9,063 per year for each person with whom they have the required visits with each month. The District will pay $4,563 of this, leaving the federal government to pay $4,500. This means $1,869 per person in annual savings to the District. For the soon-to-be realized $11 million in savings for the 5,871 PSH slots funded in or before FY 2021,[84] lawmakers should reallocate those dollars into the homeless services system to help us move towards functional zero. This did not happen in the FY 2023 budget.

One caution on net savings is that PSH Plus service costs will be higher because of the more intensive service model with medical and behavioral health care on site. There is not a current estimate of how much more PSH Plus will cost, leaving less than $11 million for services outside of PSH. Some of these costs could be reduced if a public-facing medical clinic is co-located at the PSH Plus site, which could then bill Medicaid for some of its services.

Ensuring Success: Lessons from Lived Experiences of Unhoused Residents and from Case Managers

Grounded in the framework that interventions that explicitly address racism will be most successful when informed by Black and brown residents with lived experience, this paper and its recommendations reflect direct input from, and the expertise of, individuals who are or who have experienced homelessness. DCFPI conducted eight focus groups in late summer through fall of 2022 that allowed DCFPI to gain firsthand accounts from individuals matched to PSH who have not yet moved in, PSH residents, peer educators, and case managers.

We spoke with:

- Thirteen tenant PSH voucher holders in housing in the first focus group,

- Twelve individuals matched to tenant PSH and not yet moved in in the second and third focus groups,

- Twelve men who live in a PSH building in the fourth focus group,

- Nine women who lived in another PSH building in the fifth focus group,

- Four peer educators in the sixth focus group, and

- Eleven PSH case managers in the seventh and eighth focus groups.

The People for Fairness Coalition, a local advocacy and outreach organization led by individuals who have experienced housing instability, as well as the Georgetown Ministry Center, a local organization providing day services, case management, and outreach to individuals experiencing chronic homelessness, recruited tenant voucher holders and individuals matched to PSH. The two nonprofit organizations that provide case management in the two buildings recruited building residents. DHS recruited peer educators and DCFPI recruited PSH case managers by reaching out to PSH providers. DCFPI also conducted interviews with government agency leaders, providers of homeless services, and homeless advocates. (Appendix I includes further detail on questions that DCFPI posed to participants.)

Focus group and interviewee input pointed to five core recommendations for District leaders: speed up the leasing process for those who are unhoused, strengthen case management, improve and clarify rules of site-based PSH, address behavioral health needs and prevent inflow into homelessness, and better meet the needs of an aging population.

-

Speeding Up the Leasing Process

In 2021, DC Council made a transformative investment in ending chronic homelessness by funding 1,924 PSH vouchers for individuals in the FY 2022 budget. With an additional 532 new PSH slots for individuals using federal Emergency Housing Vouchers (EHVs), the District had an unprecedented 2,456 new PSH tenant vouchers available for FY 2022. However, implementation delays have been much worse than anticipated, with only 427 of the 1,924 locally-funded PSH vouchers and 436 of the 532 EHVs leased up. At this pace, the agencies will need 30 more months to lease up all FY 2022 vouchers and an additional 9.5 months to lease up the 500 locally-funded PSH tenant vouchers available in FY 2023.[85]

These delays are due to a number of factors, including workforce shortages, an unwieldly application, and also likely the new Medicaid requirement that DHS must assess every current PSH resident and all those moving into PSH.[86],[87] Research shows that the longer people remain unhoused, the more their situations deteriorate.[88] As they wait on a PSH slot, residents are often forced to stay in places that are unsafe or in conditions that can make any existing illnesses worse. Focus group participants with lived experience affirmed that the slow pace is harmful to their physical and emotional well-being. They reported feeling discouraged and upset the longer they had to wait to move into housing, and that no one cares about them.

To get residents housed as quickly as possible, DC policymakers, particularly within DHS and DCHA, should consider the following:

Monitor Inspection Process. Case managers report very long wait times—up to three months—for the required DCHA housing inspection, which can lead to PSH clients losing apartments to other tenants. DCHA recently reported that inspections should be scheduled within one week of the voucher holder identifies an apartment. DCHA and DHS should monitor whether DCHA is meeting this goal and provide quarterly data on its track record to the ICH. If the new process does not reliably achieve wait times of one week or less, DHS and DCHA should consider these suggestions from case managers:

- Assign inspectors to specific providers so that providers have better communication with their inspectors and can troubleshoot problems; and,

- Allow PSH providers to inspect units as they are allowed to do as part of their HUD contracts.

Implement a Boot Camp to Identify and Address Other Issues. DHS and DCHA should implement a new 100-day boot camp—a practice that DC used to speed up the housing placement process for veterans experiencing homelessness—that would bring together decisionmakers in government agencies, service providers, and individuals with lived experience to systematically investigate issues and quickly develop solutions. The 100-day time span provides a sense of urgency and a shared target for making changes. A coordinated effort is key as only by acting together can the lease up process be improved. Additionally, these partners should troubleshoot individual situations where lease ups are taking a long time during the bootcamp period, ensuring everyone has a common understanding of what is causing the delays and a plan to speed up the process.

Remove Social Work Exam Requirement for PSH Case Managers. A social work degree is not a requirement to be a PSH case manager, but case managers with social work degrees must receive licensure, which in DC requires passing an Association of Social Work Boards exam. Those without a social work degree do not have to be licensed. Experts have criticized the test for racial bias, and recent exam data in fact shows significant racial disparities in the pass rates for the exam.[89] Providers can and often do hire case managers without licensure but then must terminate that employment when case managers fail to pass the exam. At least one local provider has terminated strong case managers of color who did not pass the exam.[90] The DC Board of Social Work or the DC Council should remove the exam requirement as Illinois just did—a change that led to almost 3,000 new, licensed social workers in the first six months of 2022, or about seven times as many as recruited in the first six months of 2021.[91]

Provide a One-Time Boost to PSH Providers. The switch to Medicaid billing should lead to higher funding for providers, because they no longer have to negotiate their own rates with DHS. This higher funding could be enough to increase staff salaries to improve retention but there is uncertainty about how much it will cost to implement new billing procedures, including new software and additional staff time. A one-time financial boost to providers could help them offer bonuses or higher salaries to improve retention in the immediate term. After providers have fully transitioned to Medicaid billing, DHS and providers can examine whether the Medicaid reimbursement is sufficient or should be increased to sustain higher staff salaries. DHS should survey providers about how much funding they would need in FY 2023 until the transition to Medicaid is complete.

Borrow or Use Volunteer Case Managers on an Interim Basis. At least one national organization has offered to lend staff with case worker or social worker experience to the District to help address caseload backlogs, and they have also offered to recruit other organizations for the effort.[92] If this doesn’t yield enough social workers, the District and providers could recruit volunteers, as some providers have already done.

Explore Affordable and Efficient Transportation Options for Clients During the Lease-Up Process. Participants matched to PSH expressed that easy, affordable transportation to day services, case manager meetings, and apartment viewings would speed up their ability to submit their application and locate a unit. Scheduled van transportation serves shelter sites and has recently been brought back to PEP-V sites, but is lacking at bridge housing sites, apartment-style shelter for individuals who have been matched to housing. This makes it difficult for clients to visit potential apartments. DHS should survey clients in bridge housing about what kinds of transportation assistance would be most helpful such as free Metro passes or shuttles to nearby Metro stations.

Pay Security Deposits Promptly. Many buildings require a security deposit from tenants at lease signing but case managers report that DCHA often takes 30 to 60 days after move-in to provide it. As a result, some buildings illegally do not rent to voucher holders in anticipation of this delay.

Create Working Group to Study Moving Procedures and Make Recommendations. Currently there is no official policy at the DCHA on paying for and helping individuals move to new units once they have already lived in PSH.[93] DHS does have a policy, but case managers and providers report that it is neither widely enforced nor understood. The ICH should create a Working Group, including individuals with lived experience with homelessness, to study moving procedures and make recommendations. Current client input should inform this work and the process should include recommendations for helping clients find new units, paying for new security deposit and application fees, and help with packing and physical moving. Before moving into PSH sites, providers should also be clear to clients under what circumstances and how they can transition out of a site.

-

Strengthening Case Management

The experiences of focus group participants underscore what other case studies and analyses also show—a healthy, supportive relationship between a case manager and client is crucial to the success of housing individuals who have been unhoused over long periods of time. [94] In DCFPI’s focus groups, participants with lived experience of homelessness had high praise for some case managers and significant criticisms of others, but they shared a belief that case management has a major impact on their ability to connect with benefits and services, troubleshoot problems, and complete paperwork on time. One noted “you can feel the compassion” of one provider. Others reported they feel as if staff do not care or judge them, leaving them feeling “demoralized.” Likewise, some providers and case managers in the focus groups reported feeling unable to meet their clients’ needs and asked for more and better training.

The following recommendations would help to strengthen the relationship-building between provider and client.

Ensure Case Managers Regularly Contact Clients. PSH clients reported varying levels of consistent contact with their PSH caseworkers. For example, a few PSH residents reported that case managers seemed to forget about them once they moved into housing. Many long-time residents reported that they felt stable but would appreciate regular check-ins from their case manager. With the shift to Medicaid billing, providers must meet with clients and log visits in order to get reimbursed. DHS should monitor Medicaid implementation to see if it resolves the issue and if not, should consider contacting a random sample of clients at various providers to see if visits are indeed happening.

Evaluate Case Management Quality. Participants with lived experience recognized that many of these jobs, which require dealing with people in crisis and with a diverse set of needs, are tough. One suggested a probationary period during which staff work in the field and are then evaluated. One peer educator suggested using peer educators as “secret shoppers” to observe and report back on the quality of services. Another mentioned that for jobs in retail, applicants have to respond to questions on how they would handle certain situations and suggested such questions as a way to screen candidates for homeless services jobs. DHS does survey clients, at least annually, on their experiences in the program. DHS is also in the process of implementing a secret shopper program across the agency. DHS and homeless service providers should monitor this program once implemented to ensure new case managers provide quality services.

Hone Case Management Training. Case managers reported in focus groups that they felt their training was inadequate, specifically on supporting individuals with substance abuse problems and providing services in a trauma-informed way. New case managers receive a two-day training from DHS that includes many topics including conflict management, trauma-informed care, and understanding special needs. DHS also surveys case managers about the effectiveness of individual trainings. DHS and homeless service providers could also supplement current trainings with opportunities for peer learning and workshopping challenges and should survey case managers to get their feedback on training needs. For example, at least one case manager thought it be helpful to have some training after getting to know clients as it could be an opportunity to troubleshoot specific cases.

Improve Case Manager Retention. Most focus group participants with lived experience reported that case management turnover, both in the PSH program and other homelessness programs, is a huge issue. One participant reported having six PSH case managers in two years while another reported having four in two months. One participant described it as a case manager “get[s] my information and they disappear.” Participants find it difficult to repeat their story and needs to each new case manager. Some had experienced a gap in coverage when they did not know who to contact for help. One person reported having no contact from the provider for six months after her case manager left.

The National Health Care for the Homeless Council finds that turnover among case managers undermines the counseling supports and the health and housing stability of clients.[95] DHS is now offering hiring and retention bonuses for PSH case managers and the switch to Medicaid billing comes with higher reimbursement for service providers. Providers should increase case manager salaries, possibly with funds available under the new Medicaid reimbursement system, and work with DHS to identify other strategies that can improve retention.

Improve Coordination between PSH Case Manager and Other Case Managers/Outreach Workers. Participants matched to PSH as well as day program and outreach staff expressed frustration around case manager coordination. PSH clients often rely on and have more frequent contact with their day program, shelter, and outreach workers, but these workers often do not know the status of clients’ PSH applications. These workers also reported that clients are sometimes dropped from the PSH program before they can move into housing because case managers fail to contact staff members for help locating clients. DHS should consider ways to facilitate communication between PSH providers and other case managers and outreach workers, exploring whether the steps of the housing process can be added to the Homelessness Management Information System (HMIS) or whether another tool can be used.

Ensure Better Information Sharing to Clients. Many focus group participants lacked information on all the supports available to them. For example, one did not know that the PEP-V program offered toiletries. Another did not realize they had only six months to locate an apartment after they received their PSH voucher. One mentioned turning down site-based PSH without knowing about the advantages, such as security and onsite case management. A number of participants reported learning things from others during the focus group that they did not know. Even peer educators who have received training on the homeless services system lacked basic information.

Town hall meetings on available housing programs, new programs coming online, and accessing other resources and benefits could be held at shelters and at locations that would be convenient for people living outside. Peer educators or the ICH Consumer Engagement Work Group could test out new informational materials explaining where to get basic needs for food and clothing met, making sure they are accessible to clients.

Offer Classes on Healthy Living Habits. Focus group participants reported that many clients struggle with grocery shopping, cooking, and housekeeping when they move into their own housing and case managers do not have the bandwidth to help clients develop these skills. The stress of these responsibilities can lead to people abandoning their housing, and residents with very poor housekeeping can be evicted. DHS and PSH providers should explore offering and expanding cooking lessons to more PSH residents as well as offering classes on cleaning. These classes could be held in person or via video.

-

Improving and Clarifying Rules of Site-Based PSH

Homeward DC 2.0 calls for a large expansion to site-based PSH because the District has primarily invested in tenant-based vouchers.[96] While tenant vouchers meet the needs of many residents, the new strategic plan notes that some people need more. For example, individuals who have intersected with the carceral system reported discrimination from landlords who are unwilling to rent to them. Additionally, some clients, particularly women, expressed a preference for communal living.[97] And as DC’s homeless population is aging, many need intensive, onsite supports that are only feasible in site-based PSH. To meet this need, the ICH recommends that DC launch a new site-based PSH Plus program, that would offer onsite medical care and at least one meal per day. Before implementing these expansions, the District should gather feedback from clients to ensure that the model serves their needs and concerns.

The focus groups revealed that many individuals with lived experience have major hesitations about living in site-based PSH. They voiced concerns about “draconian” and ever-changing building rules, reported dealing with awful conditions such as mold, pests, and a lack of heat and hot water. They shared their confusion about the moving process for residents already in PSH and fear they would not receive a tenant voucher if they wanted to move. Also, service providers reported that employees who work for the property management company, rather than the service provider, often do a poor job working with clients with behavioral health or other needs.

The District can take steps to both assuage fears and address the issues that were common among focus group participants. Policymakers can:

Encourage PSH-Matched Clients to Tour Existing Buildings. Focus group participants who had experienced homelessness worried that site-based PSH would be “chaotic” like their experience with large shelters. Some participants were also hesitant to consider site-based PSH because they worried about a lack of privacy, limitations on hosting guests, strict and changing rules, substandard conditions, and inability to move. Tours allow potential clients to get a feel for the site-based environment and ascertain from property management staff what the rules are to better determine what suits their individual needs.

Standardize Property Management Approach and Training. DHS should create a standard approach to property management and training for property managers based on best practices, including ensuring commitment to the PSH mission and model as well as clearly outlined roles.[98] One DC PSH provider implemented such a training and found it led to improvement in services.

-

Addressing Behavioral Health Needs and Preventing Inflow into Homelessness

Housing is crucial for people dealing with mental illness. DBH staff report that without stable housing, people with mental illness are more likely to deviate from their treatment plans.[99] Additionally, homelessness can be a traumatic event that exacerbates a person’s mental illness.[100] And homelessness among people with mental illness leads to more contact with the carceral system as well as higher rates of criminal victimization.50[101] In the focus groups, case managers and participants with lived experience reported that moving into tenant-based PSH can be lonely and can feed into depression. Most people are moving from shelter or encampments, where they have lived with other people. A peer educator reported that most people he knows would like to make connections in their new community.

The following recommendations would help to address behavioral health needs and prevent inflow into homelessness:

Expand and Strengthen DBH’s Housing Programs. One of DBH’s strategic objectives is to prevent and minimize homelessness by maximizing housing resources for the most vulnerable District residents with serious behavioral health challenges, including people who are homeless, returning from institutions, or transitioning to more independent living.[102] DBH administers its own housing programs to meet this objective, but the need far outweighs the available slots, meaning individuals with behavioral health needs often end up in the homelessness system rather than receiving DBH housing before they become homeless.[103] Expanding DBH’s housing programs would allow clients to access housing without having to become homeless first and then wait for PSH. DBH should convene a working group with its clients, providers, and advocates to assess gaps and current options, and to make recommendations on which programs to expand. DBH should also increase the maximum rent allowed in its Home First subsidy program. The program currently only pays up to 80 percent of the 2011 Fair Market Rent, which is just $905 for an efficiency apartment, making it very difficult for clients to find units. [104] [105]

Increase the Number of Psychiatric Beds. There are not enough psychiatric beds in hospitals or standalone facilities for DC residents who need them.[106] As a result, facilities often involuntarily commit these individuals for short periods of time and then release them because there are not enough beds to meet needs. Increasing the number of available beds can help clients stabilize while they wait to move into PSH or DBH housing.

Provide Services for Residents with Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBIs). TBIs are injuries to the head that disrupt the function of the brain.[107] Research suggests that TBIs may be a risk factor for becoming homeless, and individuals experiencing homelessness are also at a higher risk of suffering from a TBI because they are more likely to be victimized by assault, experience trauma, and have substance use disorders that can cause falls.[108] There are very few TBI services in the District because it is not an official billable diagnosis in DC’s behavioral health system. Research has found that people with TBIs may get terminated from housing or services because of disruptive behavior or inability to follow instructions.[109] The Department of Health Care Finance should allow providers to bill for TBI services.

Investigate Day Program Options. Given the isolation and depression reported by individuals with lived experience with homelessness, DHS and providers should explore possible day program options in the community and supplement these activities if needed. Participants with lived experience expressed a desire for wellness activities, like exercise classes or gym access.

Improve DBH Services. Many residents who experience chronic homelessness receive outpatient services from DBH. Unfortunately, the quality of many services is poor, and in the case of Assertive Community Treatment (ACT), it does not follow best practices like housing assistance and 24-hour crisis response.[110] DBH should use the Tool for Measurement of ACT (TMACT) to measure fidelity to the ACT model and improve services.[111] DBH and DHS should work together to outline how DBH service providers should work with PSH providers.

-

Addressing the Needs of an Aging Population

In the District and across the country, more seniors are experiencing homelessness.[112] At the annual PIT count in 2022, 40 percent of single adults counted (1,336 unhoused individuals) were ages 55 or older.[113] For some of these individuals, neither PSH or PSH Plus offer enough support, and they will need the type of support offered by assisted living facilities or nursing homes. Many of these facilities do not accept clients experiencing homelessness, particularly those with behavioral health needs. To address this need, the District funded its first assisted living facility for people experiencing chronic homelessness, but the building is currently undersubscribed. This is in part because the District requires that Medicaid recipients in assisted living facilities contribute all of their monthly income to the facility except for a small personal needs allowance (PNA) of $100.[114] According to one provider for this facility, many individuals who considered the building reported they preferred PSH where they would contribute just 30 percent of their income towards rent, even though PSH does not offer the intensity and types of services they need.

Increase the PNA. The District sets the amount for the PNA, which is supposed to cover the monthly costs of a resident’s needs not covered by the facility, such as medication copays, toiletries, and clothing. It has not been adjusted for inflation for years and leaves residents with barely any disposable income. The District should study the actual costs that assisted living recipients face and speak with potential assisted living clients about what they believe is reasonable and then increase the PNA accordingly.

Explore Whether the Concerns of Assisted Living and Nursing Home Providers Can Be Addressed. Rather than relying solely on building new facilities, which takes time, the District should explore what concerns assisted living and nursing home providers have and whether these concerns can be addressed so that they can accept homeless individuals.

Appendix I: Focus Group Questions

For this report, DCFPI conducted eight focus groups in between summer and fall 2022. Focus groups, as a method, provide insights into what people think and provide a deeper understanding of the phenomena being studied. Our focus groups were intended to gain firsthand accounts from individuals matched to PSH, PSH residents, peer educators, and case managers. We spoke with:

- Thirteen tenant PSH voucher holders in housing in the first focus group,

- Twelve individuals matched to tenant PSH and not yet moved in in the second and third focus groups,

- Twelve men who live in a PSH building in the fourth focus group,

- Nine women who lived in another PSH building in the fifth focus group,

- Four peer educators in the sixth focus group, and

- Eleven PSH case managers in the seventh and eighth focus groups.

Each focus group lasted approximately two hours. Individuals matched to PSH, PSH residents, and peer educators received a gift card for their participation. Individuals who had to travel received a Metro card as well. The conversations from these focus groups greatly helped to inform this report.

While the conversation flowed to several different topics, the following are the general questions that DCFPI posed to the groups:

For PSH clients:

Let’s first go around the room. Please introduce yourself by giving your name, age, race, pronouns, how long you experienced/have been experiencing homelessness, and how long you’ve be in PSH.

- Please raise your hand if your answer is yes:

Did you know that Permanent Supportive Housing can help with:

- Paying for:

- Apartment applications & security deposits

- Furniture

- Other household items (like dishes and sheets)

- Adaptive aids (like shower grab bars)

- Moving

- Understanding your rent amount, lease, and program rules

Of these items, what has been most helpful for you or would have been most helpful? This could be what was most helpful for getting and staying in housing or helped you get more stable overall.

- Ask participants to raise hands if their answer to the following question is yes:

Did you know that PSH can also help with:

- Applying for benefits and accessing food banks

- Connecting to friends, family, or community like clubs or activities

- Learning cooking, housekeeping, shopping

- Scheduling appointments and transportation

- Getting a home health aide

Of these items, what has been most helpful for you or would have been most helpful?

- What other help would you like to have?

- Has PSH helped you reach your personal goals?

- What other things were most helpful in ending your homelessness? Were the following services helpful:

- Day center

- Outreach worker

- Shelter/shelter staff

- Prevention services

- What, if anything, could have prevented your homelessness?

- Do you ever have problems with:

- Your landlord. What were those problems?

- Your property manager. What were those problems?

- Your building’s security guards. What were those problems?

Does your case manager help you address these issues?

- Were you offered other kinds of PSH [site, project or tenant, explain differences]? If so, why did you choose the PSH type you are in?

- What are your perceptions and/or experiences with site-based PSH?

- What are your perceptions and/or experiences with tenant PSH?

- Have you experienced discrimination in the homeless services system?

- Have your PSH services been culturally sensitive, meaning that your case managers have understood your background, traditions, and language needs?

- Have you moved while in the PSH program? If so, what help was provided? Did you receive help with:

- Finding a new unit

- Packing

- Moving

- Paying for move

- Paying security deposit and first month’s rent

Why did you move?

- Have you wanted to move while using PSH and have not been able to? Why did you want to move? Why were you not able to move?

- Have you had or wanted to have custody of minor children while in PSH that requires a larger unit? Were you provided help with moving to a larger unit?

- Would you like to share anything else about your experiences with PSH and homeless services?

For clients matched to PSH

Let’s first go around the room. Please introduce yourself by giving your name, age, race, pronouns, how long you experienced/have experiencing homelessness, and how long since you were matched to PSH.

- Did you know that Permanent Supportive housing can help with:

- Paying for:

- Apartment applications & security deposits

- Furniture

- Other household items (like dishes and sheets)

- Adaptive aids (like shower grab bars)

- Moving

- Understanding your rent amount, lease and program rules

Of these items, what has been most helpful for you or would be most helpful? What was most helpful for getting into housing or helped you get more stable overall?

- Ask participants to raise hands if their answer to the following question is yes:

Did you know that PSH can also help with:

- Applying for benefits and accessing food banks

- Connecting to friends, family or community like clubs or activities

- Learning cooking, housekeeping, shopping

- Scheduling appointments and transportation

- Getting a home health aide

Of these items, what has been most helpful for you or would have been most helpful?

- What other help would you like to have?

- What other things would have been helpful in ending your homelessness (ask open ended and then give prompts):

- Day center

- Outreach worker

- Shelter/shelter staff

- Prevention services

- Have you experienced discrimination in the homeless services system?

- Have your PSH services been culturally sensitive, meaning that your case managers have understood your background, traditions, and language needs. How?

- What if anything could have prevented your homelessness?

- Were you also offered other kinds of PSH [site, project or tenant, explain differences]? If so why did you choose the PSH type you are in?

- Ask about perceptions/experiences of site-based PSH

- Ask about perceptions/experiences of tenant PSH

- Do you want to have custody of minor children while in PSH that requires a larger unit? Were you provided help with moving to a larger unit?

- How long have you been in the lease up process? What, if anything, would help speed up this process?

For case managers:

- Does your agency’s PSH help your client with:

- Paying for

- Apartment applications & security deposits

- Furniture

- Other household items (like dishes and sheets)

- Adaptive aids (like shower grab bars)

- Moving

- Understanding your lease and program rules

Of these items, what do you think is most helpful to your clients?

- Does your PSH help clients with:

- Applying for benefits and accessing food banks

- Connecting to friends, family or community like clubs or activities

- Learning cooking, housekeeping, shopping

- Scheduling appointments and transportation

- Getting a home health aide

Of these items, what do you think is most helpful to your clients?

- What other things are most helpful in ending a client’s homelessness?

Were the following supports helpful?

- Day center

- Outreach worker

- Shelter/shelter staff

- Prevention services

- Do you face challenge that the government could help resolve with:

- Landlords

- Property managers

- Security guards

- When your clients are offered other kinds of PSH [site, project or tenant, explain differences) why do they accept your kind? Why do they reject the other kinds?

- How easy is it to help clients move? What do you think should be offered to help clients with moves?

- Have you had client who wanted to have custody of minor children while in PSH that requires a larger unit? Were you able to provide them with help moving?

- What could be done to speed up lease up process?

- What could be done to help people retain their housing?

- As DC houses more people, many of the folks we will be trying to serve have either refused housing several times or struggled in PSH and became homeless again. What should providers and the government do to help these folks get into and stay in housing?

- Do you believe the Coordinated Assessment and Housing Placement (CAHP) system is working well? Do you have any recommendations for improvements?

- Many jurisdictions are stopping the use of Vulnerability Index-Service Prioritization Decision Analysis Tool (VI-SPDAT). What do you think about the District’s use of the VI-SPDAT? If the District does not use the VI-SPDAT, what should it use?

- What do you think about the use of case conferencing in the CAHP process?

- Any other feedback on how providers or government could improve?

Appendix 2: Recent Positive Developments Put DC in Striking Distance of Ending Chronic Homelessness

Historic Investments in tenant PSH Vouchers. With funding resulting from the “Homes and Hearts Amendment Act of 2021,” which imposes a modest increase in the income tax rate for the District’s wealthiest residents, the Council added 1,924 new PSH vouchers for individuals to the FY 2022 budget. The District also created 532 new PSH slots for individuals with federally-funded EHVs in FY 2022. The Mayor then added 500 new PSH vouchers in the FY 2023 budget.[115] This represents a historic investment in tenant-based PSH. From FYs 2016 to 2021, the District funded an average of 418 new vouchers annually.[116]

Transparency and Limits on Fees plus Expansion of Fees Paid for By PSH Vouchers. Many PSH providers and clients report that landlords often charge fees explicitly to exclude voucher holders because vouchers have traditionally not covered fees. They have also reported that landlords are not transparent about amounts and types of fees until after a rental application fee has been submitted. The “Eviction Record Sealing Authority and Fairness in Renting Amendment Act of 2022” requires landlords to provide a list in writing of all fees before a potential tenant submits an application fee. And in a separate effort, PSH vouchers now will cover up to $1,000 in fees for the first year of tenancy and $500 in subsequent years for each participant.

Credit History Prior to Voucher Receipt No Longer a Consideration. The “Eviction Record Sealing Authority and Fairness in Renting Amendment Act of 2022” forbids landlords from considering a voucher holder’s credit prior to their receipt of the voucher. This will help many clients who struggled to pay bills before the receipt of their voucher and as a result have poor credit or have no credit history.

Allowing Tenant Voucher Recipients to Self-Certify Eligibility Factors. Since July 2022, tenant voucher recipients are allowed to self-certify eligibility factors, such as identity, when an applicant cannot easily obtain verification documentation.[117] Photo IDs are difficult and time consuming to obtain, particularly because an applicant must have a birth certificate. Early evidence from the implementation of the federally-funded EHVs that allowed self-certification indicates that it could lead to much quicker lease ups. The average number of days from an EHV client being assigned to a provider and an application being completed was 19 days compared to 126 days for locally-funded PSH clients who were not allowed to self-certify at that time.[118]

Reevaluation of Assessment Tool. DC uses the Vulnerability Index- Service Prioritization Decision Analysis Tool (VI-SPDAT) as the common, standardized tool to assess vulnerability and service needs. It is one of several criteria for prioritizing individuals for available housing.[119] The creator of the VI-SPDAT and other communities are discontinuing its use, in part because it lacks a racial and gender equity lens.[120] Three studies found unintended racial disparities in survey results.[121] The ICH is exploring alternatives to the VI-SPDAT that would incorporate racial, gender, and sexuality equity adjustments.

Streamlining PSH Application Form. DCHA and DHS are working with The Lab @ DC to simplify the PSH application form. The Lab @ DC is a DC government agency that “uses scientific insights and methods to test and improve policies and provide timely, relevant and high-quality analysis to inform the District’s most important decisions” and has worked with numerous government agencies, residents, and experts in user-centered design to remake forms to be more accessible.[123]