Displacement is a multi-faceted problem that has come in many forms at different times throughout the District’s history, and Black and brown communities have borne the brunt. Generations of policy choices, both on the local and federal level, have led to racial segregation, wealth disparities, and the steady disappearance of affordable housing, creating the conditions that drive displacement today.[1],[2] Despite recent local investments in housing production and new investments to support homeownership, DC has underfunded or failed to fund more immediate- and medium-term strategies to support residents with the lowest incomes and stem the displacement of residents of color.

A singular or hyper-focus on the production of new housing will not prevent displacement of residents whose rents are steadily rising now, or who are currently living in “affordable” buildings in dangerous disrepair that threaten the safety of occupants. The District must adopt a holistic approach that not only employs multiple strategies, but that also brings the intention of repairing historic and structural harm that has left Black and brown residents more vulnerable to displacement pressures. This means acknowledging past and ongoing racist policies that have caused harm and actively creating policies to repair those harms and meaningfully involve residents to identify their needs.

To prevent displacement and work toward a more racially and economically equitable DC, District leaders should:

- Quickly stabilize housing for those at risk of immediate displacement.

- Invest in housing preservation, not just new production.

- Hold landlords accountable to tenants.

- Protect the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) and bolster programs that make TOPA successful.

- Put significant funding toward income and work support programs.

- Invest in Black homeownership and community wealth-building opportunities.

This agenda, while not exhaustive, offers a holistic framework that aims to take on multiple forms and causes of displacement. These recommendations are grounded in existing research and were developed in partnership with local stakeholders, including tenants, tenant organizers, and affordable housing experts.

The Causes, Impact, and Evidence of Displacement

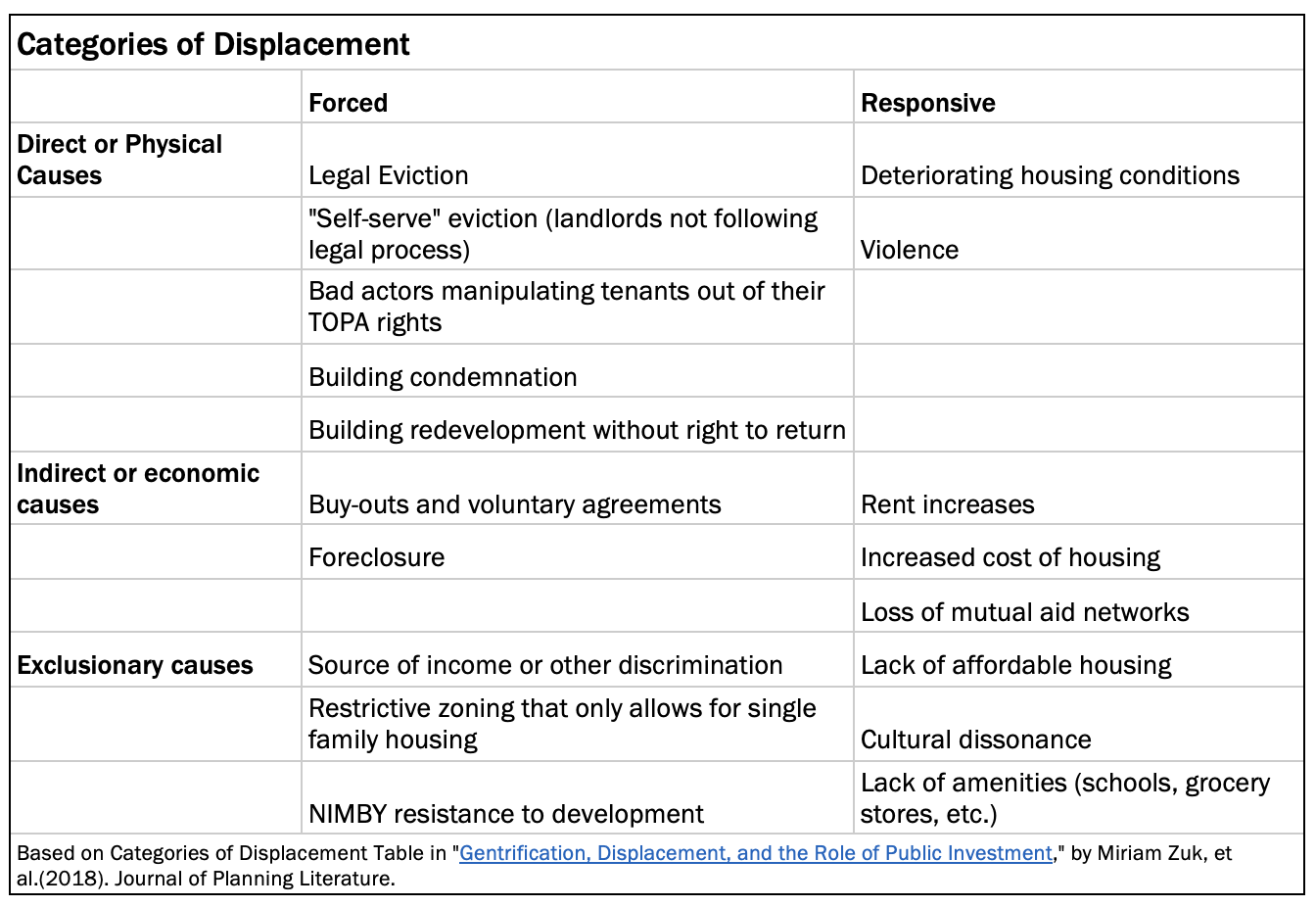

Displacement happens when residents are pushed out of their homes or neighborhoods due to pressures that are generally out of their control.[3],[4] It has many causes, including increased housing costs, eviction, landlord harassment, and deteriorating housing conditions (Table 1). It also can happen both at the household level, when a family can no longer afford their housing, and at the community level, when a population of a single identity group is pushed out of an area.[5] Displacement at the community level contributes to a communal feeling of “dispossession”—a term that comes from scholarship on colonial displacement of indigenous populations.[6] Remaining residents experience a loss of community as their neighbors are displaced, their cultural or religious institutions leave, and as commercial and retail centers no longer serve their needs.[7]

Similarly, in her book “Root Shock,” Dr. Mindy Fullilove shows how forced disconnection from one’s community increases risks for “every kind of stress-related disease.” On a communal level, displacement disrupts systems of community care that are essential to neighborhood stability.[8] Displacement also means that residents lose access to resources or areas with more abundant resources, such as grocery stores or educational institutions. Displaced home-owning families may also lose assets and wealth if predatory real estate interests convince them to sell their homes below what they are worth.[9]

Black communities in the District have experienced the harm of “root shock” as a result of policies such as urban renewal and racially restrictive housing covenants that defined where Black residents were and were not permitted to live. Black communities continue to experience the longstanding effects of those explicitly racist policy choices as they are priced out of their neighborhoods.[10] Immigrants to DC, particularly those who left their home countries due to violence or poverty, are experiencing their own form of root shock as they seek stability in immigrant neighborhoods in the District. [11] Root shock and displacement are not inevitable. The District can use new and existing tools to support residents with low incomes and prevent displacement of residents of color.

The history of housing and displacement in the District summarized below is primarily focused on the ways that anti-Black racism has created wealth inequality and segregation, causing harm to Black communities in the District. This report acknowledges, but does not go into great depth into, the history of other communities of color, starting with colonization, the initial displacement of indigenous peoples, as well as Latinx, and Asian American and Pacific Islander communities. However, the policy recommendations are informed by those histories and the current lived experiences of residents with a diversity of racial identities.

A History of Racism Laid the Groundwork for Today’s Displacement in DC

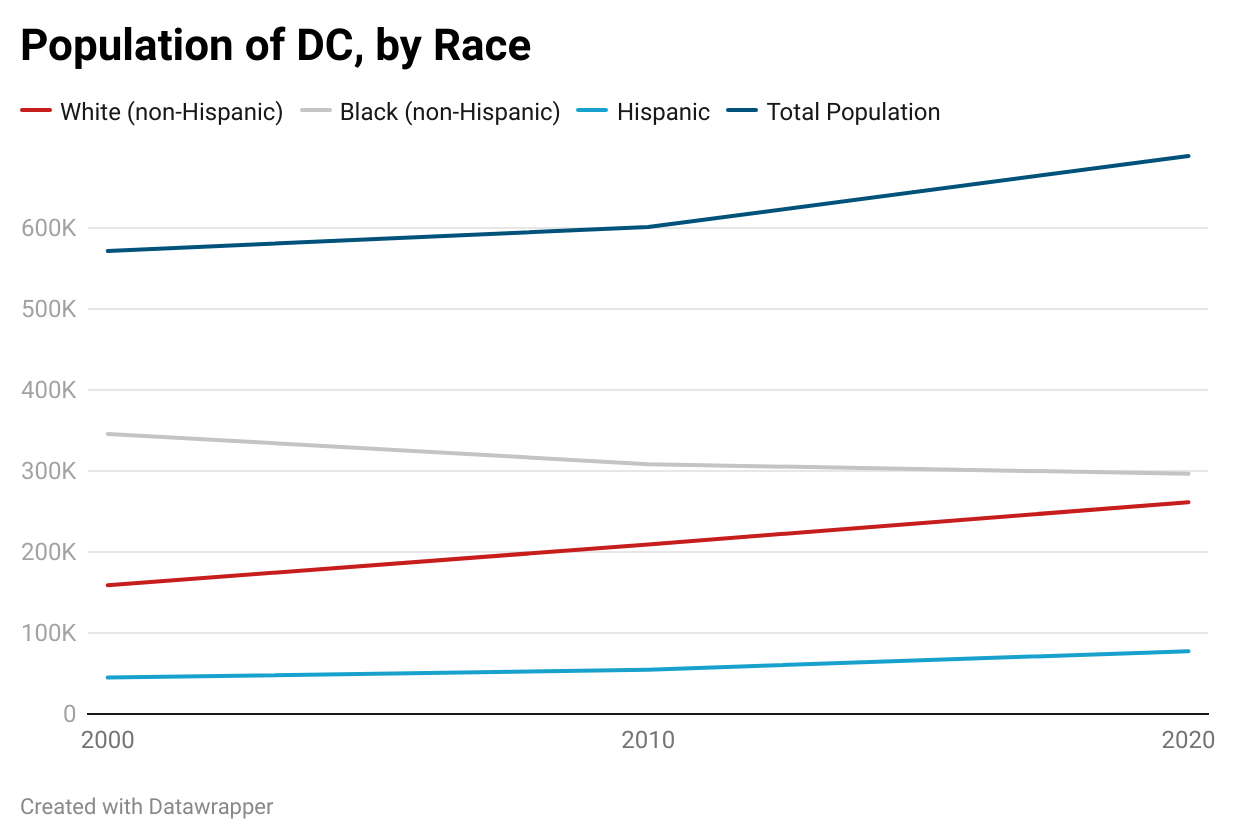

DC was the first majority Black major city in the US and had a reputation as a haven for Black opportunity even during slavery. It was referred to as “Chocolate City” for more than 50 years. But DC’s Black population began to decline following its peak in 1970.[12] Between 2000-2020, the Black population declined by nearly 58,000 while the white population grew by almost 86,000, an analysis of census data shows.[13] In 2000, 32 of DC’s 62 residential neighborhoods were majority Black, but by 2020, only 22 residential areas remained majority Black.

The enduring legacies of racist policies and practice – such as residential segregation, redlining, restrictive covenants, barring Black people from federal employment, and access to Homestead and New Deal programs, among others – denied Black households in DC equitable access to housing and employment and continue to harm all communities of color today.[14]

During the first half of 20th century, racist policies and practices defined where Black Washingtonians could live in the District. Both developers and organized white residents systematically barred Black and other residents of color from entire blocks and neighborhoods. Racially restrictive covenants legally prevented Black residents from buying certain houses.[15] The federal government further institutionalized racial segregation by, for example, making race a criterion for insuring mortgages and barring Black households from qualifying for mortgages from mainstream banks.[16]

By artificially enhancing the value of areas where only white people lived, covenants incentivized displacement of Black residents and the redevelopment of Black land into white-only neighborhoods while disincentivizing investment in areas where most Black DC residents lived. For example, white community members in 1920s Chevy Chase worked with the National Capital Park and Planning Commission to use eminent domain to seize land from a neighboring community of Black families for a new whites-only school and recreation center.[17],[18]

Economic conditions and the beginning of suburbanization in the early 1930s and 1940s further entrenched segregation. The economic downturn of the Great Depression and World War II’s impacts on production led to a significant decrease in housing construction. Limited production of new housing meant that existing urban housing stock declined steadily in quality while an increasingly affluent white middle class drove an increase in demand for housing. When the federal government passed the Housing Act of 1949, mortgage financing became available mostly for white Americans, prompting a sudden increase in construction, primarily in the suburbs.[19]

These large new suburban developments, coupled with racist practices in the real estate industry contributed to “white flight” as white residents left urban areas for the suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s.[20] In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that racial covenants were unenforceable, suddenly opening up opportunities for prospective Black buyers in areas where they had previously been barred.[21] In a practice known as “blockbusting,” realtors convinced white homeowners to sell their homes out of the fear that Black residents moving into their neighborhoods would lead to a reduction in their property values, accelerating white flight to the suburbs.[22] The rapid suburbanization led to a shift in private and public investment from urban to suburban areas.

Without investment, urban areas were left to deteriorate until the federal government targeted them for “slum clearance” and redevelopment in a project known as “urban renewal.” These efforts began with Southwest DC and completely demolished majority-Black neighborhoods in order to make room for highways leading to newly developed white suburbs.[23] Urban renewal in DC in the mid-20th century forced between 15,000 and 17,000 Black residents over the Anacostia river as the District intentionally constructed all of its new public housing east of the Anacostia.[24] Very few, if any, families displaced by urban renewal received compensation or assistance in relocating.[25]

This history sets the stage for the forces of gentrifying revitalization: as new public and private investment increases in areas that had long experienced disinvestment, more affluent residents move to those neighborhoods and alter the economic and social landscape.[26] With limited housing stock, the increased demand for housing in these areas increase rents and home and property values, putting financial pressure on residents with lower incomes.

How Displacement Happens in Current Day DC

One primary factor driving displacement in the District today is the high cost of housing, which is the result of an increase in demand for housing and a slow expansion of the supply of available homes. The supply of affordable housing stock is expanding even more slowly. DC has an estimated shortage of almost 33,000 rental homes that are broadly affordable and also available for extremely low-income renters, according to a study from the National Low Income Housing Coalition.[27],[28] In contrast, the District’s goal of creating or establishing affordability covenants between 2019 and 2025 falls far short of that, set at just 12,000 new affordable housing units. This target number includes units affordable to households up to 80 percent of the area median income (AMI), not just units affordable to extremely low-income renters, or those between 0 and 30 percent of the AMI. Between 2015 and 2023, the District has produced only 1,514 deeply affordable units, a far cry from the estimated need.[29]

For residents who do not have access to significant wealth, homeownership is increasingly out of reach. The median sales price for a single-family home in DC reached $1.1 million in 2020, a 24.2 percent increase from the year before.[30] In 2021, the homeownership rate for white, non-Hispanic households in DC was 50 percent, compared to 34 percent for Black households.[31] An analysis by the Urban Institute found that only 8.4 percent of homes purchased between 2016 and 2020 were affordable to the average first-time Black homebuyer, while 71.4 percent of homes were within reach of the average white first-time homebuyer.[32]

Meanwhile, a second factor driving displacement is the declining livability and availability of existing affordable rental housing. Public housing units, owned and managed by the DC Housing Authority (DCHA), are deteriorating rapidly as the agency makes slow progress toward rehabilitation.[33] Across the District, the supply of unsubsidized affordable housing – also known as “naturally occurring affordable housing” – is disappearing as buildings age and get redeveloped with higher rents.[34]

Additionally, there are increased threats to tenants’ rights, including their right to organize and their right to live in safe housing in good repair. Some developers, seeking to maximize profit, engage in efforts to weaken and undermine the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) without repercussion.[35] The DC government’s weak enforcement of building codes has left residents across the District living in dangerous and unhealthy living conditions.[36],[37] As both the cost and demand for housing rise, residents with low and moderate incomes have limited options for housing and few avenues to defend against these threats.

Systemic racism contributes to income and wealth gaps that mean that residents of color make up a disproportionate share of residents with low incomes in the District. A 2019 report from the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development showed that Black residents are three times more likely than white residents to move due to an inability to pay their housing costs.[38] Shifts in the demographics of the District reflect this economic reality. Since 2000, the population of white residents has increased, while the number of Black residents has steadily declined (Figure 1).[39]

A Holistic Agenda to End Displacement in the District

The District needs a holistic approach to ending displacement that not only employs multiple short-, medium-, and long-term strategies, but that also brings the intention of repairing historic and structural harm that has made Black and brown residents more vulnerable to displacement pressures.

The following agenda, while not exhaustive, offers a holistic framework that aims to take on multiple forms and causes of displacement. The recommendations are grounded in existing research and were developed in partnership with local stakeholders, including tenants, tenant organizers, and affordable housing experts.

Quickly Stabilize Housing for Those At-Risk of Immediate Displacement

Too many residents at risk of displacement face an immediate crisis and can’t wait for solutions such as the production of new affordable units, which will take years to catch up to the need. A successful affordable housing strategy must take steps in the immediate term to prevent crises, including sudden spikes in rent or loss of income, that lead to displacement. The District should strengthen, and adequately fund, programs and policy tools that can do more to quickly stabilize housing and prevent displacement.

Prevent eviction by improving access to legal representation and rent support. Research demonstrates that evictions are harmful to those who experience them, often leading them to a downward spiral and setting them back for years. People who are evicted often experience education and employment disruptions, increased mental hardship, high stress levels, and an overall decrease in financial security.[40],[41] Preventing evictions is an essential part of maintaining stable communities.

As recently detailed in a report from the DC Eviction Prevention Co-Leaders Group, preventing eviction requires a cross-sector collaboration between service providers, the District government, the DC courts, tenants, and landlords.[42] To avoid eviction, tenants need access to financial resources when they are unable to pay rent and information and counseling about their rights once they are facing an eviction filing. The District can help tenants avoid eviction by facilitating further collaboration and data sharing between service providers, District agencies, and the DC Superior Court.

Each year, District lawmakers should ensure that eviction prevention programs are fully funded. For fiscal year (FY) 2024, advocates asked that the Emergency Rental Assistance Program receive at least $117 million to fully meet the need. The approved FY 2024 budget had only $43 million; less than one month into the fiscal year, the budget is proving too small to meet demand.[43]

Fund additional vouchers and improve voucher program implementation. Rental vouchers – which help cover the difference between the rent a household can afford to pay and the full rent – could be a key tool to prevent displacement but are falling short on impact, primarily because of program underfunding and significant implementation issues.

Tenant-based vouchers allow households to rent any qualifying unit: the tenant pays 30 percent of their income towards the rent and the voucher covers the rest. The District has its own locally funded voucher program, the Local Rent Supplement Program (LRSP), which lawmakers have never sufficiently funded. In 2006, the District’s Comprehensive Strategy Task Force called for approximately 1,000 LRSP vouchers per year over 15 years to meet need.[44] In the 17 years since the taskforce made this recommendation, the District has funded only 6,400 vouchers.[45] The need for vouchers so outstrips supply that the DCHA closed the waiting list in 2013, leaving many households waiting a decade or longer for a voucher.[46] As of February 2023, there are still about 13,000 households on the waiting list.[47]

There have also been serious implementation challenges with tenant vouchers. DCHA takes 52 days on average to determine whether a household is even eligible for a voucher and, once a household with a voucher has identified a place to live, it takes another 61 days to inspect the potential housing unit to ensure it meets rent reasonableness requirements.[48] This lengthy process can result in residents becoming homeless or leave them living in overcrowded or unsafe conditions for months.

DCHA has plans to address one major implementation challenge by remaking forms to be more accessible, and thereby reduce application errors and speed up the housing process.[49] DCHA has also set a goal that inspections should be scheduled within one week of a person or family identifying an apartment. Given the current timeline, DCHA should release a plan of how they plan to achieve this goal and work to ensure that applications and other paperwork are processed in a timely manner.

Invest in Housing Preservation, Not Just New Production

The District has invested an unprecedented amount of money in housing production, including $440 million in FY 2023 for the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) and another $100 million for FY 2024. The Department of Housing and Community Development (DHCD) disperses HPTF funds through a regular Consolidated Request for Proposals (RFP) Process. DHCD reviews applications from developers and makes funding decisions based on a scoring rubric and the discretion of the DHCD director.[50] Most of the HPTF funding will go to the construction of new housing units. Creating new affordable homes, including income-restricted housing that is affordable to residents with the lowest incomes, is essential to preventing displacement. However, without increased attention to and resources for housing preservation, DC will continue to lose vast numbers of naturally occurring affordable housing units as these units age and require significant rehabilitation, the costs of which would be passed on to tenants without substantial subsidy. To ensure that these units stay affordable to the tenants who currently live in them, non-profit and mission-minded affordable housing developers need low-cost financing in the short- and long-term.

Designate 25 percent of funding from the Housing Production Trust Fund for preservation. The District has a fund dedicated to preservation, the Affordable Housing Preservation Fund (AHPF), but it is intended as a “bridge loan,” meaning that it provides short-term financing for initial acquisition costs and emergency repairs. Lawmakers have not designated new dollars for this fund since FY 2022, claiming that the fund is now paying for itself through ongoing loan repayments. However, volatile market conditions, a continued spike in inflation, and the lack of permanent financing options from the District are all factors that slow repayments into the AHPF. This makes it difficult for the fund to be self-sustaining.

There is no designated source of District financing for preservation projects outside of AHPF loan repayments and this leaves on hold millions of public and private dollars committed to repair projects as affordable housing developers wait years for financing. Stable, designated financing is essential because it allows affordable housing developers to leverage additional financing tools and more quickly make badly needed repairs and updates to aging affordable housing stock. This would also allow for quicker repayment of short-term AHPF loans, which can then go to preserving additional housing units.

The District should set aside at least a quarter of HPTF allocations for preservation projects. While preservation projects technically can apply for HPTF, the criteria DHCD uses to select projects make it difficult for preservation projects to compete with new production. In the Consolidated RFP issued in December 2021, only two of the 22 projects selected for underwriting were preservation projects.[51] By setting aside a portion of the HTPF for preservation, the District can ensure more preservation projects move forward, and that those projects are financially viable, while increasing housing stability for residents in buildings in need of repair.

Improve administration of programs that support affordable housing rehabilitation. Lawmakers and agency staff should ensure sufficient funding for the District’s Small Building Program, as well as its proper implementation. This program provides funds to landlords who struggle with the costs of maintaining small rental properties while keeping rents affordable.[52] In FY 2022, DHCD set the goal of serving 75 properties with this program. Despite the widespread need for rehabilitation assistance, DHCD received just six applications and zero properties received funding through the program, indicating that too few landlords are aware of the program and that the program’s requirements may be overly restrictive.[53] DHCD has stated that the team administering this program is working on improvements to the application process. The District should ensure that these improvements are implemented in FY 2024.

Strengthen and expand rent control to keep cost of housing in check. Residents living in rent controlled buildings in DC are less likely to experience displacement than those in non-rent controlled housing.[54] To ensure that DC’s rent laws continue to protect tenants from unaffordable rent hikes, DC Council should pass comprehensive rent control reform to strengthen and expand the District’s rent stabilization laws.[55] DC can expand rent control by eliminating the exemption for buildings built since 1976, which has the effect of shrinking the reach of rent control every year. The District should update the law, exempting buildings from rent control only for their first 15 years following construction, after which they would be covered. Council should also cap rent increases at inflation, because allowing prices to grow beyond that—as is currently allowed—puts affordable housing increasingly out of reach for District residents living on low or fixed incomes.

Hold Landlords Accountable to Tenants

Owners of rental housing have the responsibility to provide safe housing that is in good repair and complies with District housing code. Unfortunately, across the District, many affordable buildings are falling into disrepair because landlords are either unwilling to pay or unable to afford to bring buildings up to code. People who rent in these buildings, particularly tenants with lower incomes, must either choose to live with poor housing conditions or face a form of displacement called “eviction by neglect,” in which they relocate for their own safety. [56],[57]

Increase enforcement to ensure landlords comply with building code and respect tenants’ rights. The District has taken steps to hold some landlords accountable for extreme neglect. For example, the Attorney General has brought lawsuits against some of the most egregious slumlords, with some tenants even receiving financial restitution. [58] However, the issue of deteriorating building conditions is becoming more widespread as building stock ages and the cost of maintaining property rises. District lawmakers and agency staff must ensure that housing providers abide by District laws regarding tenant safety and well-being.

The District should impose meaningful consequences for landlords who consistently fail to keep their properties up to code, which violates tenants’ right to safe, decent, and sanitary housing. One way to improve enforcement is to impose consequences on landlords who exceed a certain number of citations or whose housing code violations go so far as to threaten the life and safety of the tenants. For example, landlords who have been found to be frequent or egregious violators could be required to sufficiently demonstrate that housing code violations have been remedied in order to maintain their license to operate their rental properties.

Protect the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act and Bolster Programs that Make It Successful

The Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) was adopted more than 40 years ago as a strategy to preserve affordable housing and prevent displacement. It gives District renters the first right to purchase a property when an owner decides to sell. And, even when purchase isn’t possible, it improves tenants’ bargaining position during the sale or conversion of a building, including on any changes in rent under new ownership. TOPA helps to combat instability and dispossession by giving tenant associations a legal right to negotiate with potential buyers about the future of their homes and communities. This ability is important to preserving community stability and combating dispossession.[59]

A recent study commissioned by the DC Council finds that TOPA is fundamentally successful at preventing displacement and preserving affordability.[60] The study also finds that the success of TOPA is currently at risk because tenants lack sufficient information about their rights. This leaves renters vulnerable to bad actors who take advantage of them and convince them to sign away their rights. In these scenarios, tenants lose the ability to negotiate for housing and rent stability and often end up relocating without knowing that they had the right to organize with fellow renters to stay.

Reinstate, Expand, and Fund the First Right to Purchase Program. Even when tenant associations are able to act on their TOPA rights, they and the developers they choose to work with struggle to find financing to purchase and preserve the buildings as either affordable rental units or as limited equity co-operatives. The District should expand and fund the First Right to Purchase Program (FRPP), a program that offered many tenants with low and moderate incomes, the majority of whom are Black or brown, their first opportunity for homeownership by providing low-interest loans to tenant groups.

DHCD, the agency that administers FRPP, has not accepted applications for this program in more than five years and it is no longer funded. FRPP should be funded and expanded, as recommended in the aforementioned study, to offer financing to multi-family properties with characteristics that make it hard for them to find other financing options due to deferred maintenance or high costs of acquisition and renovation that would require a purchaser to significantly raise rents, displacing tenants with low incomes.[61]

Enable community-based organizations to support tenant organizing and preempt predatory real estate practices. DHCD publishes a weekly notice of all properties that have registered an intent to sell. Previously, DHCD gave advance notice of these filings to community-based organizations (CBOs) that offered TOPA technical assistance. DHCD no longer follows this practice, which means that technical assistants are often unable to reach tenants before brokers with a financial interest approach tenants to sign away their rights.[62] The District should require that DHCD give these CBOs, many of which receive District funds to offer technical assistance, advance notice of filings to ensure that tenants understand their rights under TOPA and are able to make informed decisions.

Dedicate Substantial Funding Toward Income and Work Support Programs

A household’s ability to maintain stable housing depends on their ability to pay for it. Increased housing costs put residents with low incomes, and those who have experienced chronic unemployment, at risk of displacement. The District needs to invest deeply in income and work support programs to ensure that its residents can earn sufficient income not only to pay for their housing, but to invest in their futures.

Provide robust income supports so residents can better afford to stay in their homes. The District should expand basic income support programs, including Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, its guaranteed income pilot Strong Families, Strong Futures, and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). These supports promote financial stability and help prevent “responsive” forms of displacement.

The District can also adopt a local Child Tax Credit (CTC) to further reduce poverty and hardship and help families meet basic needs like paying the rent.[63] This would complement the EITC, which boosts the incomes of low- and moderate-income families but does little for those who face steep, persistent barriers to employment and have little to no income.[64] A DC CTC would help address the inability of work-focused cash transfers to reduce hardship and inequality for the most disadvantaged Black residents, in particular, who because of structural racism experience enormous barriers to stable employment and are much less likely to have savings or other financial supports to leverage in tough times.

Invest at scale in low-barrier employment and training programs that rapidly connect jobseekers to earned income. Unemployment in the District is extremely inequitable. Black workers experience chronically higher levels of unemployment and underemployment than white workers, and nearly half of all unemployed Black workers in 2022 were out of work for six months or more.[65] To redress structural barriers to work for Black residents and help ensure that anyone who wants to work can find a job, the District should bolster its investments in employment and training strategies that quickly connect residents to paid work, provide supportive services, and offer education and training that meets workers where they are and prepares them for career advancement opportunities. [66] Examples of these types of earn-and-learn approaches include subsidized employment and transitional jobs opportunities, including through employment social enterprises, on-the-job training, and paid pre-apprenticeship programs that lead to apprenticeship positions. It is critical that these programs are designed to screen in, rather than screen out, potential participants. A “zero exclusion” approach to employment program service delivery can strengthen programs’ commitment to equitable outcomes, ensure resources are directed to workers who would most benefit, and get more people working quickly.[67]

Increased funding for subsidized employment strategies in particular, including the Department of Employment Services’ existing transitional jobs program, can yield myriad positive outcomes for the District and its residents. Half a century of evidence demonstrates that subsidized employment can help advance racial equity and results in wide-ranging benefits for structurally excluded workers, their families, employers, and communities.[68] Among other positive outcomes, these programs put money into the pockets of people who would not otherwise be working, increase family economic stability, improve educational outcomes for the children of subsidized workers, lower rates of longer-term poverty, reduce recidivism, allow employers to grow their businesses, and boost local economies.[69]

A guaranteed jobs program is the most expansive and inclusive approach to subsidized employment. To truly ensure that no worker is left behind, DC should create a guaranteed jobs program that can quickly facilitate meaningful connections to good jobs, circumvent racial bias and discrimination in hiring, and lift the job quality floor for all workers.

Invest in Black Homeownership and Community Wealth Building

Generations of racist policies and practices excluded Black people in the District and across the country from the benefits and wealth-building that come with homeownership.[70] Disparity in mortgage lending, rising property values, and the financial burden of maintaining aging homes also contribute to declining Black homeownership in the District. [71],[72] The legacies of discriminatory policies and practices and of economic exclusion are reflected in homeownership rates and disparities in generational wealth. Since 2005, Black homeownership rates have declined from 46 to 34 percent.[73]

Double the Size of DC’s Down Payment Assistance Program. Racial disparities in both income and intergenerational wealth leave Black DC residents less likely to afford a home in the District. An analysis by the Urban Institute found that only 8.4 percent of homes purchased between 2016 and 2020 were affordable to the average first-time Black homebuyer, while 71.4 percent of homes were within reach of the average white first-time homebuyer.[74] Having a robust down payment program is important for lowering this barrier for Black prospective homebuyers.

DC’s Black Homeownership Strikeforce (the Strikeforce), an appointed group of government and public experts on housing and racial equity, identified the Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP) as the District’s main tool for tackling the racial homeownership gap.[75] In FY 2022, 74 percent of HPAP borrowers were Black and 61 percent identified as female. In FY 2023, the District more than doubled the maximum loan amount to $202,000 in an effort to expand homeownership opportunities for HPAP program participants amidst high housing prices.[76] However, the budget did not expand funds for the program, leaving it with insufficient funding to meet demand. HPAP recipients continue to face challenges such as high interest rates and high competition for very few homes available for purchase. The District should at least double funding for the program to better meet demand. It also should evaluate whether the variations in loan amount by income and family size are adequate relative to the high costs of homes in the District.

Implement Other Recommendations from Black Homeownership Strikeforce. The Strikeforce released a set of recommendations for additional policies and programs that could increase the number of Black homeowners in the District. Lawmakers have modestly moved forward with two of those recommendations: expanding the level of assistance available to applicants through HPAP and creating and funding legal assistance to low-income households facing barriers to passing on a family home through the Heirs Property Assistance program. These programs must receive sufficient and consistent recurring funding. While these programs both serve important purposes, they are not enough on their own to preserve and expand Black homeownership in the District.

To improve access to new and existing homeownership programs, the District should follow the Strikeforce recommendation to create a comprehensive online platform so that residents can easily access information about the District’s homeownership programs. The DC Council should also consider legislation to protect homeowners from unwanted, predatory solicitations from investors seeking to purchase their homes.

Address policies that perpetuate the racial wealth gap. DC’s property tax circuit breaker, also known as Schedule H, cuts off or reduces property taxes when they’ve become too high relative to household income.[77],[78] Schedule H is available both to resident homeowners and renters, who are assumed to pay a portion of DC property taxes in the form of higher rent.[79] Only residents with lower incomes are eligible for the credit and the size of the credit is scaled to the amount by which a taxpayer’s property bill exceeds a certain percentage of their income.

The District should improve and expand the property tax circuit breaker. Currently, the maximum credit limits how much property owners with low incomes can benefit, particularly when they are in rapidly appreciating properties. The District should eliminate the cap on Schedule H, ensuring that lower-income homeowners actually pay just 3-5 percent of their income in property taxes. Additionally, the District should ensure that the property tax thresholds for each income band are applied incrementally to prevent abrupt jumps in property tax bills with modestly increased incomes. A final improvement to the credit would be to expand the income eligibility for non-seniors to equal that for seniors ($78,600). All of these changes would prevent displacement of lower income homeowners in the District.

Massively increase support for community ownership initiatives. The District should invest in homeownership models, such as community land trusts (CLTs) and limited equity cooperatives (LECs), that benefit both the community and the individual homeowner. The Douglass Community Land Trust, based in Ward 8 and serving all of DC, is a community-controlled organization that owns a plot of land and rents or sells the building on top of that land at permanently affordable rates to residents with low incomes. Because Douglass CLT owns the land and keeps the housing affordable, it operates as a tool for keeping people and families living on lower incomes in their neighborhood, even as surrounding real estate prices rise.[80]

The District should commit to providing consistent funding for community land trusts. In FY 2022, the Mayor proposed, and the Council approved, a one-time investment of $2 million for the Douglass Community Land Trust.[81] Once those funds are dispersed, they will fund the creation and preservation of 75 new, permanently affordable units. Moving forward, DC lawmakers should prioritize recurring funding for land trusts, which will translate into the creation of more badly-needed low-cost homeownership options.

The LEC model is another form of community ownership that keeps homeownership within reach for people and families with low- and moderate-incomes. While LECs do not own entire plots of land, they operate a property ownership model for members that shares with CLTs the goal of maintaining affordability of a neighborhood over the long run by limiting the re-sale value of the housing units.[82] Through this model, membership shares are typically very affordable and allow members to buy in, often without needing to take out a loan. LECs offer sustainably affordable homeownership opportunities in areas where low- and moderate-income households would otherwise be unable to afford to live. An expanded and fully-funded FRPP would enable tenant associations across the District to collectively purchase their buildings to create LECs.

[1] Peter Marcuse, ”Interpreting Public Housing History,” Journal of Architectural Planning and Research, Autumn 1995.

[2] Lance Freeman, ”America’s Affordable Housing Crisis: A Contract Unfulfilled,” American Journal of Public Health, May 2002.

[3] George Grier and Eunice Grier, “Urban Displacement: A Reconnaissance.” Bethesda, MD: Grier Partnership, 1978.

[4] Miriam Zuk, Ariel H. Bierbaum, Karen Chapple, Karolina Gorska, and Anastasia Loukatou-Sideris, “Gentrification, Displacement, and the Role of Public Investment,” Journal of Planning Literature, Vol 33(I) 31-44, 2018.

[5]Rohit Acharya and Rhett Morris, “Reducing Poverty Without Community Displacement: Indicators of Inclusive Prosperity in US Neighborhoods.” Brookings Metro, 2022.

[6] Asa Roast, Deirdre Conlon, Glenda Garelli, and Louise Waite, ”The Need for Inter-Subdisciplinary Thinking in Critical Conceptualizations of Displacement,” Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 2022.

[7] Peter Marcuse, “Gentrification, Abandonment, and Displacement: Connections, Causes, and Policy Responses in New York City.” Journal of Urban and Contemporary Law, 1985.

[8] Dr. Mindy Thompson Fullilove, “Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America and What We Can Do About It.” One World Ballantine Books: New York, 2005.

[9] Lisa Bates, ”Gentrification and Displacement Study: Implementing an Equitable Inclusive Development Strategy in the Context of Gentrification.” Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations, 2013.

[10] ”Mapping Displacement: From Alley Clearance to Redevelopment,” Mapping Segregation in Washington DC, 2019.

[11] Jefferson Morley, ”The Mount Pleasant Miracle: How One D.C. Neighborhood Quietly Became a National Model for Resisting Gentrification,” The Washington Post, January 25, 2021.

[12] Campbell Gibson, Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States,” US Census Bureau, September 2002.

[13] Steven Overly, Delece Smith-Barrow, Katy O’Donnell and Ming Li, “Washington Was an Icon of Black Political Power. Then Came Gentrification,” Politico Magazine, April 15, 2022.

[14] Richard Rothstein, “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Out Government Segregated America,” Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, 2017.

[15] “Legal Challenges to Racially Restrictive Covenants,” Prologue DC.

[16] “How the Federal Housing Administration Shaped DC,” Prologue DC.

[17] Black Families Once Owned Part of Lafayette Park,” Historic Chevy Chase DC, Accessed on October 6, 2022.

[18] Neil Flanagan, “You Should Know About George Pointer,” Washington City Paper, July 19, 2018.

[19] Jason Richardson, Bruce Mithcell, Juan Franco, “Shifting Neighborhoods: Gentrification and Cultural Displacement in American Cities,” National Community Reinvestment Coalition, March 19, 2019.

[20] Richard Rothstein, “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Out Government Segregated America,” Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, 2017.

[21] “The End of Legal Segregation in DC,” Mapping Segregation DC.

[22] ”Race and Real Estate in Mid-Century DC,” Mapping Segregation DC.

[23] Peace Gwam and Mychal Cohen, “Combating the Legacy of Segregation in the Nation’s Capital.” Urban Institute, Accessed November 13, 2023.

[24] Asch, Myers Chris, and George Derek Musgrove, “Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital.” Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

[25] Richard Rothstein, “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Out Government Segregated America,” Liveright Publishing Corporation: New York, 2017.

[26] Peace Gwan and Mychal Cohen, “Combating the Legacy of Segregation in the Nation’s Capital,” Urban Institute, Accessed November 14, 2023.

[27] Extremely Low Income Households defined as households earning less than 30 percent of the Area Median Income, or $42,700 for a family of four.

[28] “Housing Needs By State: District of Columbia,” National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2021.

[29] “DMPED 36,000 by 2025 Dashboard,” Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, accessed October 31, 2023.

[30] Michele Lerner, ”Report: Median sales price of houses in D.C. now exceeds $1 million,” The Washington Post, December 2, 2020.

[31] See “Black Homeownership Strikeforce, Final Report.” Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, October 2022.

[32] “Black Homeownership Strikeforce, Final Report.” Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, October 2022.

[33] “District of Columbia Housing Authority Assessment,” Department of Housing and Urban Development, September 2022.

[34] “Housing Equity Report: Creating Goals for Areas of Our City,” Department of Housing and Community Development, October 2015.

[35] Martin Austermuhle, “Bowser Offers Bigger Tax Breaks For Office-To-Housing Conversions In Downtown, But Critics Question Value,” DCist, April 5, 2023.

[36] Abigail Williams, “Columbia Heights Renters Begin Forming A Co-Op To Keep Their Building Affordable,” DCist, February 17, 2022.

[37] Morgan Baskin, “Amid Worsening Conditions, D.C. Seeks To Appoint Guardian Of Ward 8 Apartment Complex Marbury Plaza,” DCist, August 24, 2023.

[38] DMPED, ”DC Housing Survey Report,” June 2019.

[39] Based on DCFPI analysis of Decennial Census data from 2000,2010, and 2020.

[40] Matthew Desmond. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, 2017

[41] Eviction Lab, “How does an eviction affect someone’s life?”

[42] Noah Abraham, Elizabeth Burton, Leah Hendey, Lori Leibowitz, Rebecca Lindhurst, Beth Mellen, Marian Siegel, Peter A. Tatian, “A Collaborative Framework for Eviction Prevention in DC,” Urban Institute, February 1, 2023.

[43] Annemarie Cuccia, ”Overwhelmed By People Seeking Help, D.C. Cuts Off Rental Assistance After 10 Days.” DCist, October 18, 2023.

[44] “Homes for an Inclusive City: A Comprehensive Housing Strategy for Washington, D.C.” Comprehensive Housing Strategy Task Force.

[45] United Planning Organization, “DC is not Making Progress on Affordable Housing for Those Who Need it the Most,” September 2023. It should be noted that the District has funded at least 5,000 vouchers dedicated to residents experiencing homelessness.

[46] United Planning Organization, “DC is not Making Progress on Affordable Housing for Those Who Need it the Most,” September 2023.

[47] DC Housing Authority Pre-Hearing Oversight Responses, DCHA, February 2023.

[48] Vouchers dedicated to households currently experiencing homeless take additional time to process as the client’s case management needs must be assessed and the Department of Human Services reviews all applications before sending them to the Housing Authority.

[49] The Lab @ DC, “Can residents transform government paperwork?” Accessed December 7, 2022.

[50] “Housing Production Trust Fund,” Department of Housing and Community Development. Accessed November 14, 2023.

[51] DHCD, “DHCD Responses to Questions for the Performance Oversight Public Hearings on Fiscal Years 2022/2023,” February 2023, page 25.

[52] Small building is defined as a property with five to twenty units. For more, see “Small Building Program,” Department of Housing and Community Development.

[53] “Pre-Hearing Performance Oversight Responses,” Department of Housing and Community Development, March 2023.

[54] Yesim Taylor, “Rent controlled apartments may slow displacement for people of color, a report finds,” Greater Greater Washington, April 2020.

[55] Reclaim Rent Control Platform

[56] Jasper Smith, “Marbury Plaza Tenants Say They Still Live In Terrible Conditions Amid Lawsuit,” DCist, September 6, 2022.

[57] Morgan Baskin, “These Langdon Renters Say Their Apartment Building Is Dangerous. Their Landlord Is Suing To Evict Them Anyway.” DCist, June 20, 2023.

[58] “AG Racine Announces Sanford Capital Will Return $1.1 Million to 155 Tenants Forced to Live in Squalor,” Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia, November 13, 2019.

[59] Dispossession is stage of displacement when residents experience loss of community, contributing pressure to move as friends, family, resources, community or cultural institutions etc. are also displaced. Originally described by Marcuse 1985.

[60] ”Sustaining Affordability: The Role of the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) in Washington, DC.” Coalition for Non-Profit Housing and Economic Development, October 2023.

[61] ”Sustaining Affordability: The Role of the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) in Washington, DC.” Coalition for Non-Profit Housing and Economic Development, October 2023.

[62] Emily Near, ”Testimony at the Performance Oversight Hearing for the Department of Housing and Community Development,” February 13, 2023.

[63] Erica Williams, “A Child Tax Credit Would Reduce Child Poverty, Strengthen Basic Income, and Advance Racial Justice in DC,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 6, 2023.

[64] Bradley Hardy, Charles Hokayem, and James P. Ziliak. 2022. Income Inequality, Race, and the EITC. National Tax Journal, vol. 75, no. 1, March 2022.

[65] Caitlin Schnur and Erica Williams, “DC’s Extreme Black-White Unemployment Gap is Worst in the Nation.” DCFPI, July 26, 2023.

[66] Doni Crawford and Kamolika Das, “Black Workers Matter,” DCFPI, January 28, 2020.

[67] Chris Warland and Melissa Young, “Toward a Comprehensive, Inclusive, and Equitable Subsidized Employment Initiative in Detroit.” Heartland Alliance and University of Michigan Policy Solutions, November 2019.

[68] Kali Grant and Natalia Cooper, “More Lessons Learned from 50 Years of Subsidized Unemployment Programs,” Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, August 2023.

[69] https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/More-Lessons-Learned-From-50-Years-of-Subsidized-Employment-Programs-August2023.pdf

[70] Kilolo Kijakazi, Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins, Mark Paul, Anne Price, Darrick Hamilton, William A. Darity Jr., “The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital,” Urban Institute, November 1, 2016.

[71] Amelie Zinn, Liam Reynolds, “How Local Differences in Race and Place Affect Mortgage Lending,” Urban Institute, November 15, 2022.

[72] Ashley Clarke and Amy DiPierro, “This D.C. housing program is a ‘top priority.’ Why do repairs take years?” The Center for Public Integrity, March 3, 2022.

[73] “Black Homeownership Strike Force Final Report,” Black Homeownership Strike Force, Government of the District of Columbia, October 2022.

[74] See “Black Homeownership Strikeforce, Final Report.” Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, October 2022.

[75] See “Black Homeownership Strikeforce, Final Report.”

[76] Melissa Lang, “DC to Provide Up to $200K to First-Time Home Buyers in Hot Market,” Washington Post, August 22, 2022.

[77] Details on Schedule H are available in “Tax on residents and nonresidents — Credits — Property taxes,” Code of the District of Columbia § 47–1806.06, accessed August 1, 2023, (hereafter Code of the District of Columbia § 47–1806.06) ; as well as “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[78] For more discussion, see “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022

[79] For the purposes of issuing the credit, DC assumes that property taxes make up 20% of a resident’s rent.

[80] Miriam Axel-Lute and Dana Hawkins-Simons, “Community Land Trusts Grown from Grassroots,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, July 2015.

[81] ”Fiscal Year 2022 Department of Housing and Community Development Budget Chapter,” Office of the Chief Financial Officer. Accessed November 14, 2023.

[82] Meagan M. Ehlenz, “Community Land Trusts and Limited Equity Cooperatives,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, December 2014.