Summary:

- $3.8 billion in federal and local funds, a 4% reduction adjusting for inflation.

- $9 million to expand school-based mental health to 107 schools.

- $3 million to support community-based residential mental health facilities

- $22 million to support operations of United Medical Center, up from $10 million in FY 2019

- No funds to implement legislation to eliminate healthcare access barriers imposed in the Alliance program that largely serves immigrants

- $2.5 million to implement health provisions of “Birth-to-Three for All DC” legislation

- Funds to replace expiring federal aid for street outreach to people experiencing homelessness

The District programs aimed at improving health and health care access for District residents are run by the following agencies:

- The Department of Health (DOH) manages public health programs like school nursing, HIV/AIDS prevention and screening, maternal and child health home visiting programs, and some nutrition programs.

- The Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) manages the District’s public health insurance programs, primarily Medicaid and the Healthcare Alliance. These programs provide health insurance for low-income residents, serve more than one-third of DC residents, and contribute to our nearly universal health coverage.

- The Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) funds and manages behavioral health and substance use disorder, mental health programs in schools, and the District’s psychiatric hospital, St. Elizabeth’s.

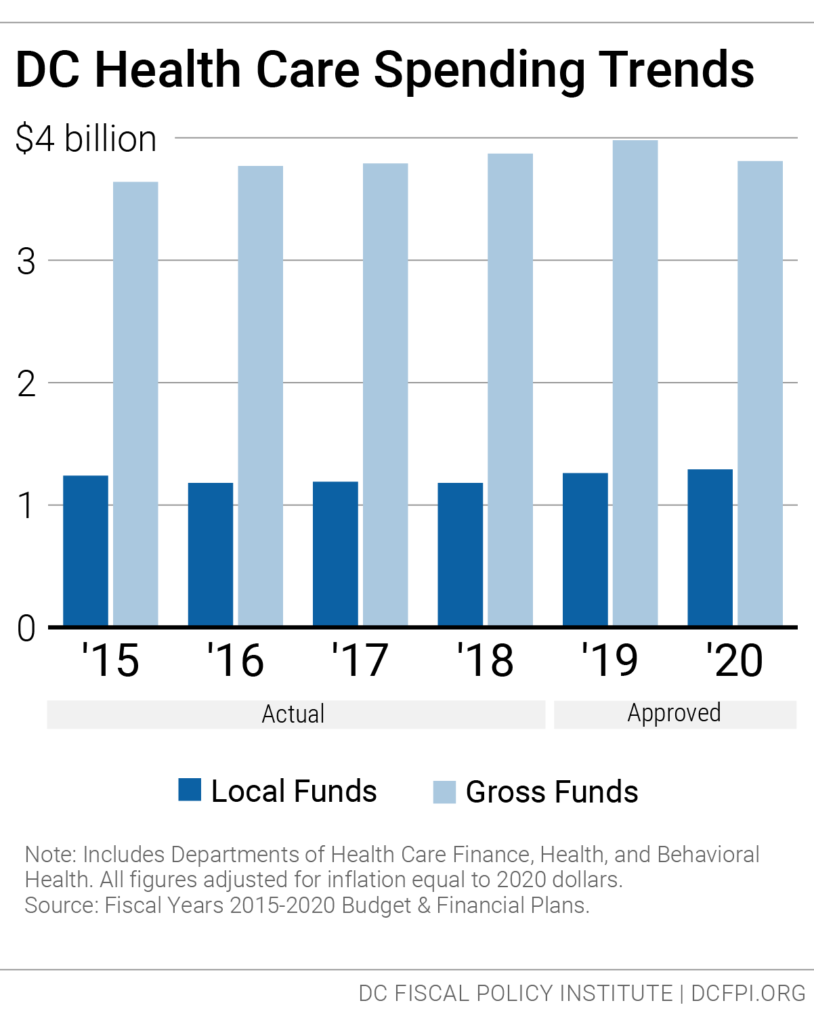

The approved fiscal year (FY) 2020 budget for these agencies totals $3.8 billion, including both federal and local sources. This represents a 4 percent decrease from the FY 2019 budget after adjusting for inflation (Figure 1). General funding from local funds will increase by 2.5 percent when adjusted for inflation.[1]

Figure 1.

The District also budgets for the DC Health Benefit Exchange Authority, an independent agency that operates DC Health Link, the District’s online portal for health insurance plans and financial assistance for those plans.

The Exchange’s funding for FY 2020 is $32 million, the same as last year, adjusted for inflation.

As discussed below, the budget keeps in place barriers that prevent participants in the Healthcare Alliance program—most of whom are immigrants—from accessing continuing coverage. The budget includes new funding for school-based mental health, adding staff to 100 schools, and new federal funds for opioid addiction.

The budget includes $2.5 million to implement some of the public health elements of the 2018 “Birth-to-Three for All DC” Act intended to support families with infants and toddlers, such as home visiting.

Health Coverage in the FY 2020 Budget

The FY 2020 budget for the Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) is $3.2 billion, a 5.6 percent decrease from FY 2019 when adjusted for inflation. DHCF is DC’s single largest agency in terms of gross funding, accounting for 23 percent of the District’s $14.6 billion total budget. The reduction largely reflects a downward revision in expected federal Medicaid funds.

More than one-third of DC residents receive health coverage through DHCF programs, about 250,000 residents through Medicaid program and 19,000 through the District’s DC Healthcare Alliance program and Immigrant Children’s Program (ICP).[2]

The local budget changes for DHCF are largely the result of several drivers.

- Change in federal matching rate for some Medicaid recipients: The federal Affordable Care Act allowed DC and states to expand Medicaid coverage, and this initially was covered entirely by the federal government. The ACA called for a reduction in the federal matching rate to 90 percent by 2020 (which is still far higher than the standard rate of 70 percent for DC). This means that the District will be expected to contribute more local funds for Medicaid. Overall, the local funds budget for DHCF will grow $34 million due to this and other factors.

- Elimination of Physician Supplemental Payment: DHCF’s budget does not renew a $1.35 appropriation made in the FY 2019 budget to provide supplemental payments to physicians in Wards 7 and 8 who agree to provide certain health care services. The supplement is needed for certain services where basic payments under Medicaid often results in a loss.

- Boost to Alliance Program: DHCF’s budget includes an increase of $11 million due to continued increases in per-person costs for the DC Healthcare Alliance program. The increase does not reflect any change in total enrollment. As discussed below, rising per-participant costs appear to be due in part to a high rate of turnover, or “churn,” in the Alliance, which stems from a burdensome requirement to renew eligibility every six months in person.

- Hospital Taxes: The proposed budget didn’t include a special tax on District hospitals that has been included in the budget on a one-time basis in recent years. These taxes, when paired with federal matching funds for Medicaid, help maintain reimbursement rates to hospitals for in-patient services for the District’s “fee-for-service” beneficiaries.[3] The DC Council added this tax back when it adopted the approved budget, which will generate $12 million in local funds and $29 million in added federal Medicaid funds.

Budget Keeps in Place Immigrant Barriers to Health Care Access

The FY 2020 budget keeps in place barriers to accessing health care through the DC Healthcare Alliance—a local program that provides health insurance coverage to low-income residents who are not eligible for Medicaid.

Because the federal Affordable Care Act allowed DC to move many Alliance participants to Medicaid, Alliance participants today are largely immigrants who are ineligible for Medicaid, including undocumented immigrants and documented immigrants who have not yet met the five-year waiting period for federal benefits.

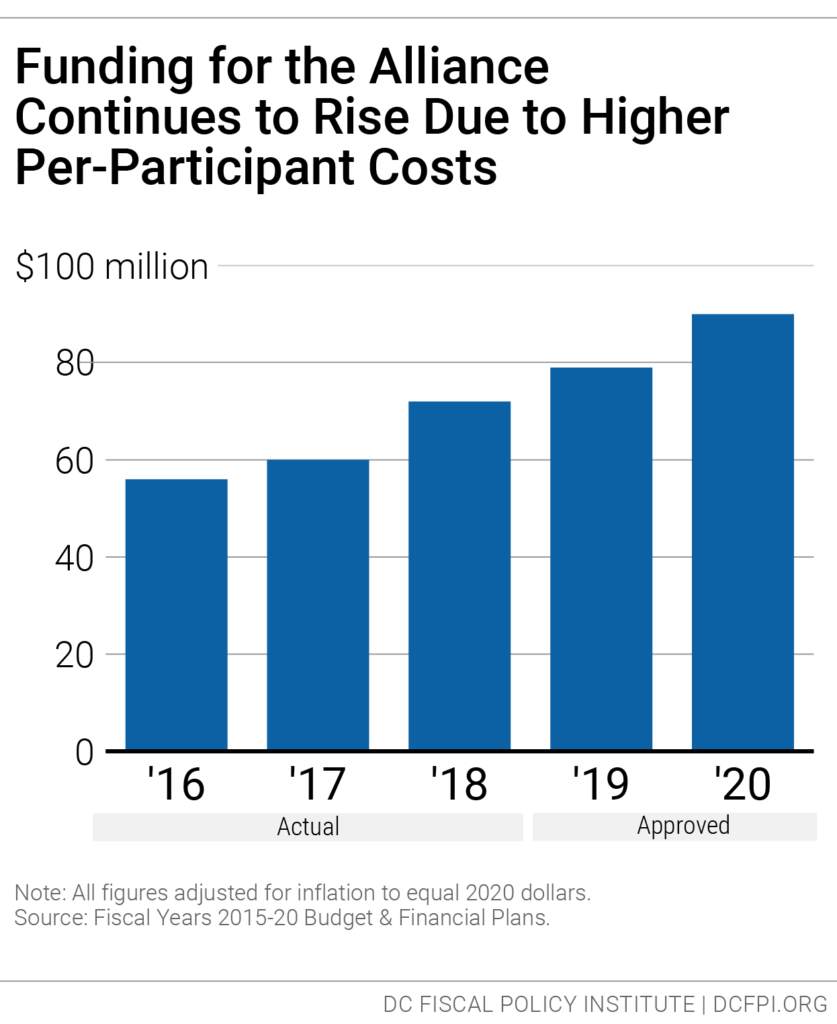

Funding for the DC Healthcare Alliance in FY 2020 is about $90 million, a 14 percent increase from last year adjusted for inflation (Figure 2). The increase does not reflect an anticipated increase in enrollment or changes in how the program is delivered. Instead it reflects an increase in per-participant costs. Alliance costs have grown sharply in recent years, even though enrollment has been flat.

Figure 2.

The cost increases likely reflect a number of factors, including a growing number of older participants. But the rising costs also stem from barriers to accessing the Alliance that the District has imposed since 2011. These barriers are likely to be contributing to poor health outcomes and, in turn, rising average participant costs.[4]

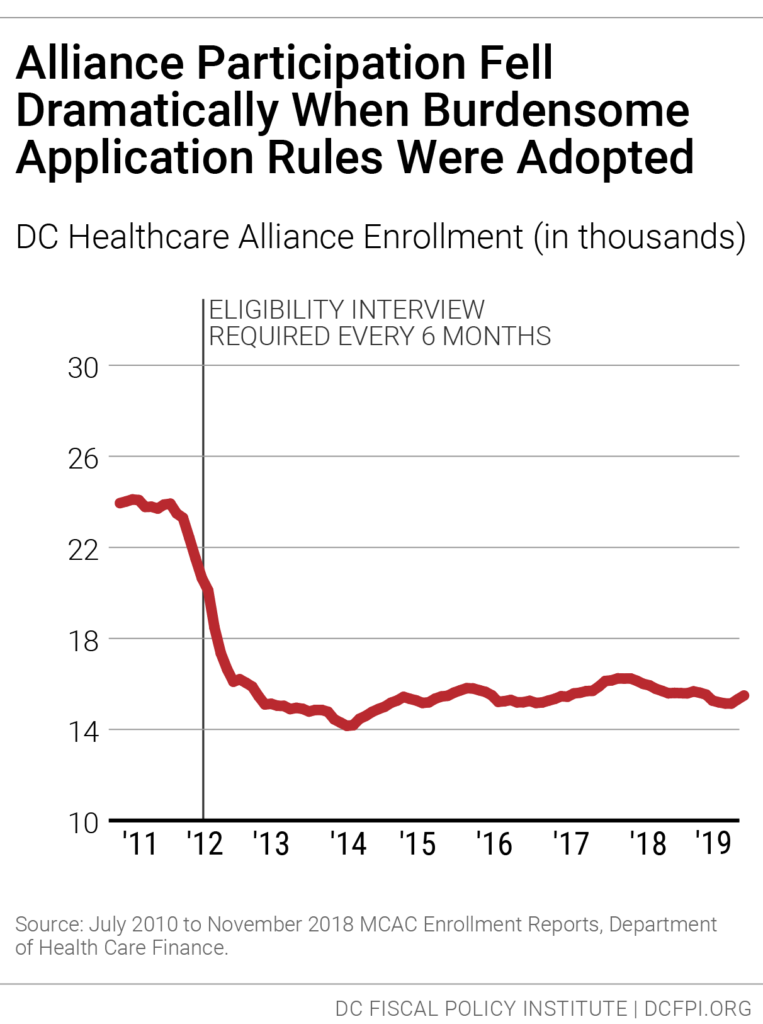

In 2011, DC implemented a new rule requiring participants to visit a DC social service center every six months to maintain their eligibility, instead of the annual recertification most DC benefit programs have. This created a barrier for maintaining Alliance coverage, leading to a sharp drop in Alliance enrollment. (Figure 3).[5]

Figure 3.

The six-month recertification requirement contributes to a very high rate of turnover, or “churn.” Currently, only about half of Alliance participants renew their eligibility at the re-certification period. This means that many Alliance participants have only intermittent health coverage.

Churn from frequent recertification results in higher costs in health program because it limits access to preventive care, which means participants often are sicker when they re-enroll, and because sicker residents are most willing to go through the process of maintaining coverage.

The six-month recertification requirement also creates problems for other residents seeking public benefits. Data collected in 2015 suggest that Alliance recipients make up one-fourth of service center traffic in a given month, even though they represent a very small portion of service center clients.[6]

Legislation adopted in 2017 would replace the six-month re-enrollment requirement with an annual requirement and allow participants to renew at community health centers. However, the legislation has a cost because it would lead to increased program enrollment. The FY 2020 budget does not include the funding needed to implement these changes, which means Alliance participants will continue to face barriers to accessing health coverage.[7]

Public Health in the FY 2020 Budget

The FY 2020 budget for the Department of Health (DOH) is $257 million, a 0.6 percent decrease from FY 2019 adjusting for inflation.

The approved budget includes some notable cuts:

- Reduction of Produce Rx food program: The budget provides $330,000 for this program, which received $500,000 in FY 2019. Under the Produce Rx program, food-insecure patients who are at risk for diet-related chronic illness are issued a monthly “prescription” for fresh fruits and vegetables by their health care provider and are given referrals for nutrition education.

- Cuts to Pregnancy Prevention: The budget removes $735,000 in one-time funds provided in FY 2019 to support a pilot at Florence Crittenton Services for pregnancy prevention activities for teen and young adult women in Wards 5, 7, and 8.

New Funds for Home Visiting Programs to Support Families with Young Children

The budget provides new resources to implement key public health provisions of the “Birth-to-Three for All” DC Act, adopted last year, which laid out a multi-year plan to provide comprehensive supports from pregnancy to age three.[8]

In particular, the budget provides $4 million to expand DC’s local investment in home visiting programs, which also are supported with federal grant funds through the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting program (MIECHV). The District funds home visiting through the Department of Health and other agencies. The FY 2020 increases are in home visiting services through the Early Head Start program operated by the DC Office of the State Superintendent.

Home visiting programs support families of young children as they transition from pregnancy to parenting. Many pregnant women and young families need help understanding and supporting their child’s development and may not know how to find the resources they need to care for themselves and their children—home visiting programs can serve as a bridge to these critical resources. Currently, Department of Health home visiting programs primarily target families of children from birth to age three in Wards 5, 7, and 8 and families experiencing homelessness.

Existing home visiting services do not reach all of the families who could most benefit from them, and the District’s local investment in home visiting is too low to adequately support the programs and their workforce.[9]

The Birth-to-Three Act calls for a $2 million increase for general home visiting programs—$710,000 toward this goal was funded in FY 2019—and an $11 million increase for home visiting for immigrant families and families experiencing homelessness through the Early Start program. The FY 2020 budget adds $4 million to implement the specialized programs.

Budget Funds Health Supports and Other Elements of Birth-to-Three Act

The Birth-to-Three Act includes several other provisions to advance healthy child development that were included in the approved budget.

Healthy Futures

Under this program, licensed professionals provide on-site mental health consultation to early childhood educators to build teachers’ capacity to reduce challenging behaviors, promote positive social emotional development, and support families. The FY 2020 budget includes $1.5 million for this program, matching the Birth-to-Three Act FY 2020 goal for this program.

HealthySteps

This evidence-based pediatric primary care program ensures the healthy development of babies and toddlers by addressing common concerns that physicians often lack time to address. This includes feeding, behavior, sleep, attachment, parental depression, and care coordination. The FY 2020 budget provides an increase of $600,000, which will allow HealthySteps to expand to two additional clinics.

Help Me Grow

The Birth-to-Three Act calls for expanding this phone-based care coordination system to help families navigate the District’s support services and maintain centralized records of developmental screenings and data. The FY 2020 budget provides $80,000 for this, just a small fraction of the $4 million needed to implement this change.

Lactation Certification Preparatory Program

The Birth-to-Three Act calls for new services to provide instruction, assistance, and mentorship to individuals pursuing a career in lactation consulting. The FY 2020 budget

provides $323,000 for this.

Behavioral Health in the FY 2020 Budget

The FY 2020 budget includes several notable targeted enhancements for behavioral health, especially with federal funds, but notable gaps in the budget for the Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) remain. The FY 2020 budget for DBH is $323 million, an 11 percent increase from FY 2019 after adjusting for inflation.

Major Behavioral Health Funding Initiatives

- School-based mental health: The FY 2020 budget includes $9 million to improve and expand services for the DBH School Mental Health Program, following recommendations of the Task Force on School Mental Health.[10] Much of the new funding will be awarded to community-based behavioral health providers, which will support clinicians and clinical supervisors in an estimated 100 additional schools. They will engage in parent and teacher consultation, school team meetings, care coordination, and crisis management.

- Federal funds to treat opioid addiction: The budget includes a $20 million federal grant to treat opioid addiction and reduce the rate of overdose fatalities.

- Residential-based services: The budget includes $3 million in new funds to support community residential mental health facilities.

- Local funds to replace expiring federal street outreach funds: Over the past three years, DC nearly doubled its street outreach to individuals experiencing homelessness and living outside, primarily funded through a federal grant. Outreach services primarily target hard-to-reach individuals who do not seek shelter or other homeless services. Outreach workers help these individuals to apply for housing and gain necessary documentation. They also help them connect with vital services like mental and physical healthcare. This federal grant expires before the end of FY 2019. The FY 2020 budget provides $3.7 million in new local funds to support a comprehensive, coordinated, and sustainably funded Street Outreach Network.

- No increase in rates for community-based providers: The budget includes no funds to increase provider rates in Mental Health Rehabilitative Services (MHRS) and Adult Substance Abuse Rehabilitative Services (ASARS). MHRS and ASARS providers offer critical behavioral health and substance abuse services that are not covered by Medicaid, such as vocational supportive employment. The rates were last increased in FY 2018, based on 2016 costs.

Budget Provides Limited Support to United Medical Center

The FY 2020 capital budget maintains funding for the construction of a new medical center to replace United Medical Center (UMC) and create an integrated health system east of the Anacostia River. Key elements of the new hospital, which is expected to be completed in 2023, are still being negotiated.

In the meantime, the District continues to support UMC operations on an ad hoc basis. The hospital is operated under contract with a private provider, which is expected to manage the hospital without further assistance. Yet UMC’s finances have been unstable, reflecting a variety of factors, including a small patient base that largely is covered by lower-paying public insurance programs and a dilapidated facility.

The budget includes $22 million beyond the contract to support UMC operations. While this is higher than the $10 million provided in FY 2019 and $30 million in FY 2018, it is well below the $40 million estimate of funds needed to maintain services at the hospital, which was the amount provided in the budget proposed by the mayor. It is not clear how the reduced funding will affect the hospital, yet it is likely to require significant staffing and service reductions. The DC Council is expected to hold hearings on the status of UMC’s operations under the reduced subsidy.

[1] In the Approved FY 2020 Budget Toolkit, DCFPI uses the most up-to-date inflation data, which is more current than the data that we used for the Proposed FY 2020 Budget Toolkit. As such, some figures may have slightly changed.

[2] District of Columbia Department of Health Care Finance, Monthly Enrollment Report, March 2019.

[3] These are hospital services for Medicaid beneficiaries not in the city’s managed care program—largely elderly residents or residents with disabilities or chronic conditions.

[4] DCFPI, “No Way to Run a Healthcare Program: DC’s Access Barriers for Immigrants Contribute to Poor Outcomes and Higher Costs,” March 18, 2019.

[5] Medicaid expansion through the ACA in 2010 shifted approximately 33,000 residents from the Alliance program to Medicaid. However, after a period of stable enrollment, caseloads began to decrease after a six-month, in-person recertification requirement began for all enrollees in FY 2012.

[6] Wes Rivers, DC Fiscal Policy Institute; Chelsea Sharon, Legal Aid Society of the District of Columbia, “Testimony for Public Oversight Hearing on the Performance of the Economic Security Administration of the Department of Human Services,” District of Columbia Council Committee on Health and Human Services, March 12, 2015.

[7] The FY 2019 budget did include three initiatives that will provide modest support to Alliance beneficiaries.

[8] For a summary, see “DCFPI Celebrates the Adoption of Birth-to-Three for All DC,” July 18, 2018.

[9] See 2018 Annual Report of the District of Columbia Home Visiting Council.

[10] See “Report of the Task Force on School Mental Health,” March 26, 2018.