Alternative bills offer fewer safeguards for workers and create more burdens for businesses

The Universal Paid Leave Act (UPLA) passed last year by the DC Council guarantees that people who work in DC can take time off from work, with pay, when they need to be with a new baby, care for an ill relative, or address their own health need.[1] The program, designed in conjunction with national experts, uses a proven “social insurance” model like Social Security, which results in low administrative costs, very limited administrative burden on employers, and a transparent system for both workers and their employers.

Despite UPLA’s many advantages, several bills have been introduced to “repeal and replace” it. Most of the alternatives focus on an “employer mandate,” where employers provide the benefit directly rather than through a public fund. A review of the alternatives shows that an employer mandate undermines each of the advantages of UPLA: easy access to benefits for workers, predictable costs for businesses, and low administrative costs.

UPLA Uses a Proven Social Insurance Model

UPLA uses a social insurance model, like Social Security and Unemployment Insurance, which has been tested and proven to work. Under UPLA, all private-sector employers in the District will pay a fixed payroll tax into a government-run fund to cover the cost of benefits for their workers. When workers experience a qualifying event—welcoming a new child into their families or addressing their own or a family member’s serious health condition—the employee comes off the company’s payroll, and receives wage replacement from the public fund. The agency administering the fund is responsible for processing claims and paying benefits.

This structure is beneficial in several ways:

- It offers a predictable tax to employers.

- It has low administrative costs and places virtually no administrative burden on employers.

- It uses a neutral third-party arbiter to decide whether a claim for benefits should be approved.

In addition, DC’s Council Budget Office found that the District can implement UPLA without affecting the ability of businesses and the DC economy to thrive. Their thorough analysis concluded that the economy will be 99.9 percent as large as it would be without UPLA, and that the adopted program is “unlikely to alter the current upward trajectory of the District’s economy.” A universal program also minimizes cost, increases employee morale, and reduces turnover.[2]

For these reasons, all of the states that currently offer paid family and medical leave use this structure.

Proposed Alternatives Would Undermine UPLA’s Strengths

Several alternative legislative proposals were introduced in the DC Council this year, with the intent to “repeal and replace” UPLA. All alternatives offer the same benefits as UPLA, but would provide them in very different ways.

- Two bills use an “employer mandate” model[3], in which all employers provide employees with paid leave directly, without a public fund to administer the benefit. Instead, employers would either “self-insure”—which means the employer pays the cost of an employee’s wage replacement directly out of pocket—or purchase insurance through a private company if that is available. All employers would have to self-insure for at least part of the program, since there are no insurance products anywhere in the country that cover all of UPLA’s benefits, particularly leave to care for an ill relative. These alternatives would also require larger businesses to pay a small payroll tax to support tax credits to some small businesses.

- Two other proposals are “hybrid” models,[4] in which small employers would pay a payroll tax to participate in an UPLA-type government-run fund, and larger employers would be subject to an employer mandate (as described above). Employers under the mandate would be required to provide benefits to their workers and also pay a payroll tax into the government-run fund to help offset the cost to small businesses.

A close review of the alternatives raises a number of concerns: an employer mandate would likely be bad for workers, bad for many businesses, and have much higher administrative costs. As shown below, an employer mandate undermines each of the advantages of UPLA: easy access to benefits for workers, predictable costs for businesses, and low administrative costs.

Below is a summary of the most significant concerns with an employer mandate or hybrid approach. (It should be noted that there are other details of the individual bills that are also problematic. A full chart including the full details of each proposal, and how they compare to UPLA, is available here.)

An Employer Mandate Is Bad for Workers

Under an employer mandate, employees request paid leave from their own employer, rather than filing a claim for benefits with a neutral government agency under UPLA. This is problematic because the employer will have incentives to deny claims. Think of the way for profit private health insurance coverage works—in which it can be quite common for workers’ benefits to be denied—versus the way that Social Security benefits are administered, in which retirees rarely have a problem receiving their payments. In addition:

- An employer mandate can increase the likelihood of discrimination for certain workers. There is evidence that employers in countries that have an employer mandate discriminate against workers they think would be most likely to take leave, especially women of child-bearing age.

- Employers who self-insure have a profit incentive to discourage employees from taking leave—or from taking the full amount of leave to which they are entitled—since they must pay the full cost of the benefit out of pocket any time an employee takes leave. This incentive will be larger in workplaces with a higher proportion of women and workers with caregiving responsibilities.

- Employees in low-wage occupations where hourly pay and shift work is common are especially vulnerable to intimidation and pressure to not to take leave. These workers often experience retaliation in the form of reduced hours, worse schedules, or even termination, and often do not even ask for benefits to which they are currently entitled, such as paid sick days.[5]

- Models dependent on employer-provided benefits prevent people from accessing benefits when they are unemployed or between jobs—even if contributions were made on their behalf while they were working. This discriminates against people recently separated from the workforce or with irregular work patterns, and acts as a deterrent for workers to switch jobs or start their own business.

An Employer Mandate Is Bad for Many Businesses

It is unclear whether an employer mandate would be any less expensive for employers than UPLA, especially since both plans require larger employers to pay a tax and pay the full costs of benefits themselves. And there is a substantial risk that an employer mandate could be costly and unpredictable for many businesses. The risks are especially great for small and mid-sized businesses.

- Under each of the alternative proposals, employers would still pay a payroll tax. This would be on top of funding benefits for their own workers, either through self-insurance or private insurance.

- Currently, no insurance product exists in the private market to provide paid family leave. It is completely unknown how long it would take to develop such a product, if ever, and what this product would cost on the open market.

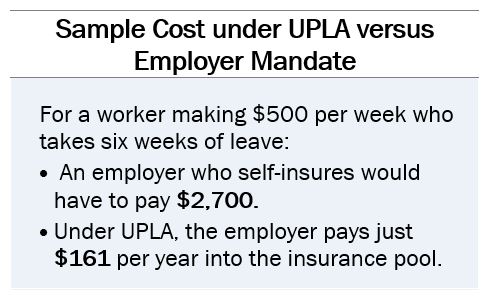

- Because no private insurance product exists, employers would have to self-insure for paid family leave, which is financially risky and administratively challenging. Self-insurance could lead to volatile costs that vary greatly from employer to employer and from year to year, since the number of workers needing leave could vary greatly from year to year. Self-insurance therefore is likely to have higher costs for many businesses, at least in some years. For example, if a worker making $500 a week takes six weeks of leave, an employer who self-insures would have to pay $2,700. Under UPLA, the employer would pay just $161 a year into the insurance pool to provide the same benefit.

- The hybrid approach may discourage business growth. Requiring employers to go from the publicly funded program to an employer mandate when their number of employees rises above a set threshold creates a cliff effect for businesses, which could be a disincentive to grow.

- Because costs will vary from employer to employer, companies that have higher usage of leave—or perhaps even perceived higher usage, based on the demographics of their workforce—will pay more, and therefore they will be at a competitive disadvantage. Again, this creates a market incentive to not hire workers likely to need leave, and to attempt to deny leave when workers seek it.

The uncertainty around costs of an employer mandate runs counter to the predictability that employers often say they are looking for. The unpredictably of an employer mandate is in sharp contrast to the fully predictable and modest cost of the 0.62 percent payroll tax that funds UPLA.

An Employer Mandate Is Bad for Program Administration and Costs

Administration of a paid leave program has three general cost categories: processing benefit claims, the cost of education and enforcement of the law, and infrastructure/IT costs. Under UPLA, all costs have been calculated and fully accounted for— and the administrative and education/enforcement costs are embedded as part of the 0.62 percent payroll tax. Under the alternative proposals, the total costs have not been calculated, and these total costs are likely to be the same or much higher than those under UPLA:

- Processing Benefit Claims: Rather than utilizing the economy of scale of a single, centralized agency, the alternate models will turn each employer into an individual program administrator. Under self-insurance, every employer would need to have staff, software, and procedures for administering this benefit. This could be burdensome to businesses and result in higher overall cost.

- Education and Enforcement: Any employer mandate would require very strong education and enforcement mechanisms to ensure that workers know about their rights, so they can access their leave benefits and can seek redress when they are wrongfully denied such benefits. The enforcement agency would need to be much larger than needed under UPLA and would therefore be more costly.

- IT/Infrastructure: A hybrid approach still requires DC to create an IT system and a division to run a public program. Start-up costs are likely to be the same as UPLA, as the IT costs of a social insurance program are relatively fixed. This means that a hybrid approach would have almost all the IT and administrative costs of UPLA plus the added administrative costs placed on all employers.

Conclusion

For the reasons expressed above, the universal social insurance model created under UPLA is the structure that makes the most sense for workers, businesses, and the broader DC economy.

[1] http://lims.dccouncil.us/Legislation/B21-0415?FromSearchResults=true

[2] http://dccouncil.us/news/entry/economic-and-policy-impact-statement-universal-paid-leave

[3] B22-0133, The Universal Paid Leave Compensation for Workers Amendment Act of 2017, and B22-0302, The Large Employer Paid-Leave Compensation Act of 2017.

[4] B22-0130, The Paid Leave Compensation Act of 2017, and B22-0334, The Universal Paid Leave Pay Structure Amendment Act of 2017.

[5] DCFPI, DC Jobs with Justice, and the Kalmanovitz Initiative at Georgetown University. 2015. Unpredictable, Unsustainable: The Impact of Employers’ Scheduling Practices in DC.