Unfortunately, a zip code can still be a determining factor in the quality of a student’s public education in DC. While DC Public Schools (DCPS) operates under rules intended to guarantee that all schools receive adequate staffing and added funds to serve students who face barriers and challenges, the reality of DCPS school allocations is far different—and worse. This is evident in the current school year, with 15 of the 19 DCPS schools that faced significant budget cuts located in Wards 7 and 8, where poverty is concentrated and the population is primarily Black.[1]

The methods DCPS uses to allocate funds across its schools is a matter of racial equity that requires immediate reform. This is especially important because strong DCPS neighborhood schools should be at the heart of an equitable education system.

While every parent or guardian can choose to send their child to their in-boundary neighborhood school or to enter the public school lottery—it really is a system of chance.[2] This is because students aren’t guaranteed a seat at their preferred school. In the 2019-20 school year, a total of 9,437 individual students were waitlisted for one or more out-of-boundary DCPS schools, and 11,861 were waitlisted to attend one or more public charter schools.[3], [4] In this context, the District needs to ensure that every student has a strong in-boundary neighborhood school.

Still, underfunding of education in DC, combined with choices that DCPS has made over allocation of scarce funds, has left many neighborhood schools behind, particularly in predominantly Black neighborhoods. For years, District policymakers have underfunded the education budget, with this year’s school budget lagging behind the city’s estimate of adequacy by about $80 million.[5]

Under these budget constraints, DCPS made a choice to fulfill its Comprehensive Staffing Model (CSM)—which sets minimum staffing requirements for each school. To fund the CSM, DCPS pays for some core staffing positions using its “at-risk funds”—resources intended as a supplement in schools with students who are at risk of falling behind academically because they face poverty, homelessness, or are in foster care.[6] Policymakers again and again have chosen to break the law, shortchanging students who need extra funds the most.

These choices reflect a priority for equality—giving all schools the same, rather than on equity—putting a priority on communities facing the greatest barriers. Future school funding decisions should be rooted first in equity, with a focus on need, not simply on enrollment. These decisions should not lead to deep cuts in schools that are predominantly Black and low-income.

While the choices DCPS makes in the future of schools are an important part of the issue, the role of policymakers is equally as important. Policymakers should fund an adequate school budget so DCPS can provide all schools with sufficient staffing. Until then, true equity in budgeting requires a prioritization of those who have been systematically harmed by poverty and systemic racism rather than equality of resources for all.

Under an inadequate budget, DCPS should prioritize equity by:

- Ensuring at risk, special education (SPED), and English Learner (EL) supplemental funds follow the student to their school, meaning school budgets are built using Uniform Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF) supplements first.

- Distributing remaining base funds to all DCPS schools using the CSM. If funding is insufficient to fulfill the CSM at each school, the CSM should be scaled back to minimize the impact of staffing cuts, but CSM reductions should be spread across all schools.

Under an adequate budget, DCPS should reform its school allocation method by:

- Following the CSM with fidelity and ensuring any new staffing model does not shift to student-based budgeting.

- Stabilizing schools with declining enrollment by ensuring no school loses more than five percent of its previous year’s budget.

- Using at-risk funds to supplement, not supplant, any funding otherwise guaranteed to a school by the CSM.

- Calculating the per-pupil minimum allotment using base funds only.

DCPS cannot make these reforms in full without an adequate budget. The mayor and Council should prioritize reaching an adequate school budget as quickly as possible, over the next two years.[7]

Background: Policymakers Allocate Public Funding to DCPS through a Formula

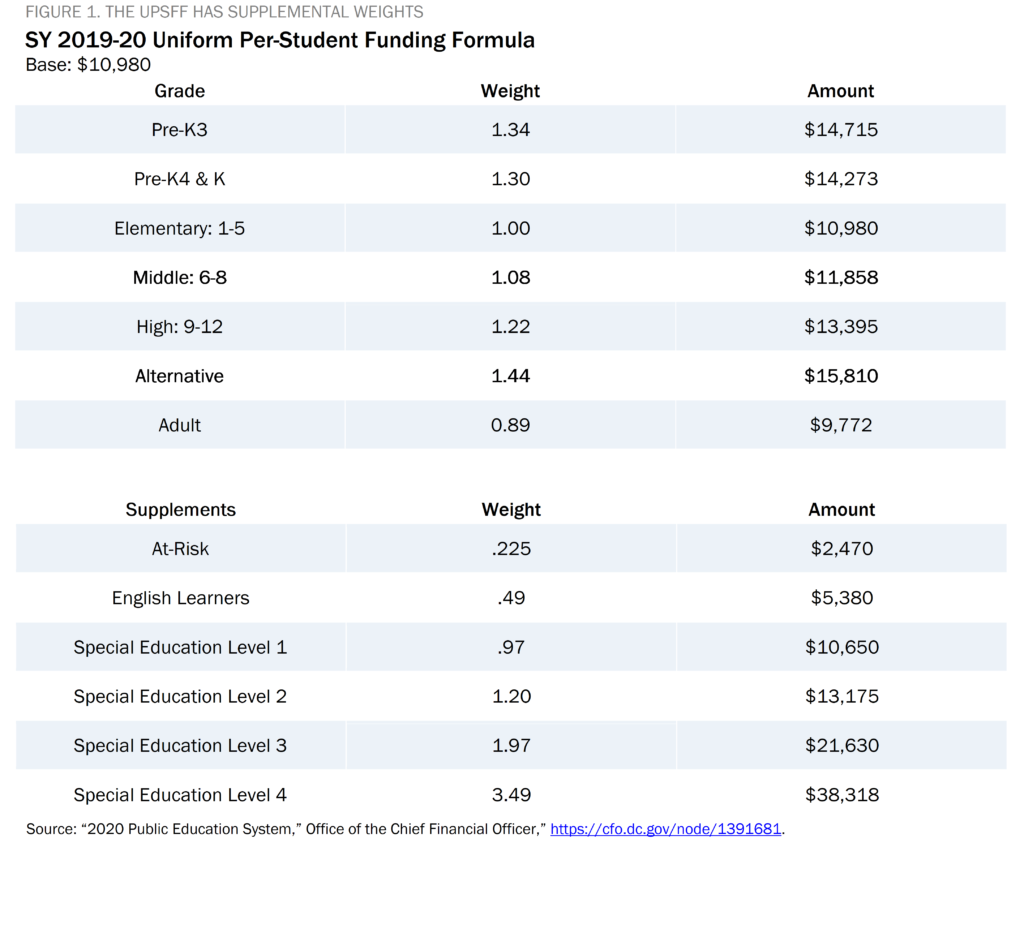

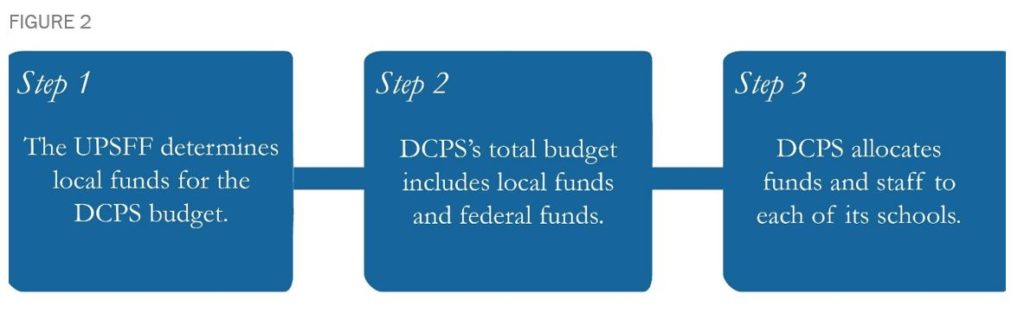

DCPS is a Local Education Agency (LEA), commonly known as a “school district,” managing 115 public schools in DC. The city allocates local funds to DCPS through the Uniform Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF). In the 2019-20 school year, the base funding amount is $10,980 for each student, a 3.0% increase from the previous year.[8] The UPSFF includes supplemental weighted funding for students in certain grades, students with disabilities, students considered “at-risk” of academic failure, and ELs (Figure 1).

DCPS Funds Schools through the Comprehensive Staffing Model

Although each student is funded uniformly, the per-pupil allocation doesn’t necessarily follow the student to the school they attend. Rather, the UPSFF determines the combined local funding for all students projected to enroll in the LEA.[9] Then, DCPS uses CSM to allocate resources to each of its 115 schools (Figure 2).

Resources in the CSM come in the form of positions, referred to as full-time equivalencies (FTE), or funding for services. DCPS uses a different CSM for each school type – elementary, middle, high, and education campus—and the staffing allowed also varies by school size (see Appendix A). By ensuring all schools have staffing to support a well-rounded education, small schools generally see higher per-pupil funding than larger schools, because salaries for required positions are spread across fewer students.

DCPS implemented the CSM in the 2008-09 school year to ensure that every school, regardless of its size, has sufficient baseline funding to cover essential positions. For example, all DCPS schools receive funding through the CSM for an instructional coach and a librarian. However, even under the CSM, schools may lose FTEs as enrollment declines. For instance, the CSM allocates one guidance counselor for every 250 students in high schools. If enrollment at a high school drops below 500 students, the school would lose its guaranteed second guidance counselor unless the school petitions DCPS central office or uses flexible funds to keep the position.

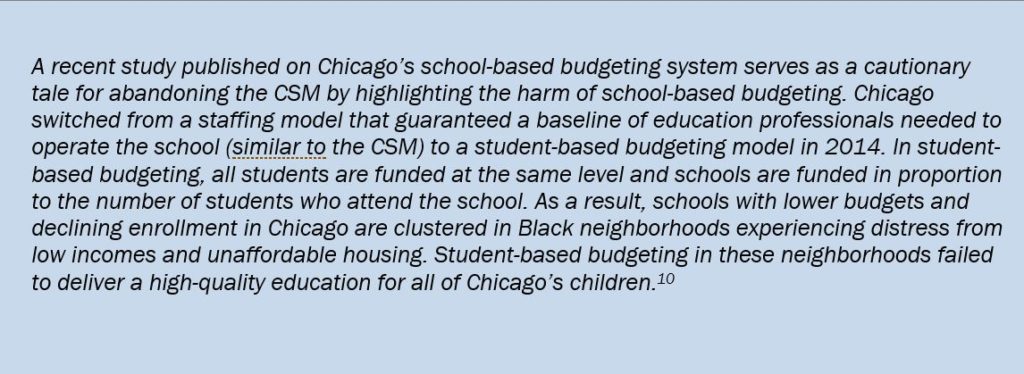

Prior to the creation of the CSM in the 2008-09 school year, DCPS funded it schools based the number of students projected to enroll at each individual school, known as “school-based budgeting.” This meant that small schools with fewer students received less funding and could offer limited programming. It also meant that schools facing even a modest decline in enrollment faced cuts in their budget. Since DCPS is the District’s “school system of right,” meaning every student has a guaranteed spot in their neighborhood school, students who happened to live in neighborhoods with smaller or declining enrollment schools had inequitable educational opportunities. Policymakers crafted the CSM in an attempt to alleviate these inequities. [See the breakout box.]

Current Flaws in DCPS’s School Funding Process

DCPS’s current school funding process is noncompliant with two school funding laws meant to provide a safeguard to protect schools with declining enrollment and students considered “at-risk” of academic failure. In addition, DCPS also sets a minimum per-pupil funding for each school, but this safeguard is flawed and doesn’t really work to ensure adequate minimal funding. As a result, DCPS is further stacking the deck against students experiencing economic injustice, especially those in Wards 7 and 8.

- Noncompliance with DCPS Stabilization Law. By law, DCPS must “provide each school with [no] less than 95 percent of its prior year allocation” unless there is a programmatic change.[11] In FY 2020, nineteen schools are facing budget cuts of at least five percent. If DCPS would have followed the law and stabilized all school budgets using UPSFF funds, it would have cost about $7 million dollars, or the equivalent of over sixty full-time teachers.[12] Given DCPS’s unique status as the by-right traditional public school system, DC Council should appropriate stabilization funds to DCPS, and it should do so outside of the UPSFF.

- Noncompliance with At-Risk Funding Law. By law, DCPS must use at risk funds “for the purpose of improving student achievement among at-risk students…the funds must be supplemental to each school’s gross budget and not supplant any UPSFF, federal, or other funds to which the school is otherwise entitled.”[13] This means that additional at-risk funds allocated to DCPS through the UPSFF must be allocated to schools on top of what the school is already entitled to under the CSM.However, a report by the DC Auditor revealed that DCPS uses about half of its at-risk funds to pay for core staff that should otherwise be guaranteed by the CSM.[14] Further, schools with higher percentages of at-risk students are more likely to receive lower base funding than schools with lower percentages of at-risk students. In other words, instead of first allocating base funding to all schools equitably and then providing additional at-risk funds for students who are at-risk, DCPS largely supplants at-risk funds, using the money as if it were additional base funding to be distributed among all schools. DCPS should allocate at-risk funds in proportion to each school’s at-risk enrollment, as the law requires.

- DCPS’s Internal Per-Pupil Funding Minimum Safeguard is Flawed. After DCPS models the CSM for all 115 schools, agency staff ensures that each school has met the per-pupil funding minimum, which is $10,000 for fiscal year 2020 (FY 2020).[15] However, the per-pupil funding minimum is a flawed safeguard for school budget equity because it includes both base funding and supplemental funding for students with disabilities, English language learners, and students considered “at-risk” for academic failure at higher levels.These funds should be excluded from any per-pupil minimum funding guarantee. Since school populations vary considerably, a school with a large percentage of students with disabilities or English Learners, for example, could appear to have a high per-pupil funding minimum when in reality their base funds per student are lower than a school with fewer students with disabilities or English Learners. In order to implement the per-pupil funding minimum safeguard meaningfully, DCPS should calculate the per-pupil funding minimum with base UPSFF funds only.

DCPS Should Improve its School Funding Model to Boost Equity

DCPS should be able to fully staff, provide wrap-around services, and hire enough teachers and other staff for all schools to ensure all students are well positioned to thrive in school. However, until policymakers adequately fund the education budget to keep up with rising costs and meet need, the CSM isn’t working well to meet the needs of all students.

DCPS plans to revise the CSM by FY 2022, which provides an opportunity for the school system to fix the current flaws in its school allocation method. It’s imperative that the new funding model prioritize equity first, by taking into consideration that low-income students have greater needs than their more affluent counterparts.

To center equity over equality, under the currently inadequate budget, DCPS should prioritize fairly distributing at-risk and other supplementary UPSFF funds before adhering to the CSM. This means:

- Ensuring supplemental funds for students identified as at-risk, special education (SPED), and English Learner (EL) follow the student to their school, meaning school budgets are built using Uniform Per Student Funding Formula (UPSFF) supplements first;[16] and

- Distributing remaining base funds to all schools using the CSM. If funding is insufficient to fulfill the CSM at each school, the CSM should be scaled back to minimize the impact of staffing cuts, but CSM reductions should be spread across all schools.

Over the long-term, as DCPS moves towards a more adequate overall budget, it should strengthen safeguards to ensure an equitable allocation system by:

- Following the Comprehensive Staffing Model (CSM) with fidelity and ensuring any new staffing model does not revert from the CSM to student-based budgeting;

- Stabilizing schools with declining enrollment by ensuring no school loses more than five percent of its previous year’s budget. Given DCPS’s unique status as the by-right traditional public school system, DC Council should appropriate stabilization funds to DCPS outside of the UPSFF;

- Using at-risk funds only to supplement, not supplant, any funding otherwise guaranteed to a school by the CSM; and

- Calculating the per-pupil minimum allotment using base funds only.

[1] Ed Lazere, “Reversing School Budget Cuts in Wards 7 and 8 Should Be a Top Priority,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, April 29, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/reversing-school-budget-cuts-in-wards-7-and-8-should-be-a-top-priority/.

[2] “Should My Child Apply?” My School DC, https://www.myschooldc.org/how-apply/should-my-child-apply.

[3] “About 2019-2020 Lottery Results,” District of Columbia Public Schools,” https://enrolldcps.dc.gov/node/61.

[4] “Waitlist Data,” DC Public Charter School Board, April 16, 2019, https://dcpcsb.org/waitlist-data.

[5] Alyssa Noth, “Educational Equity Requires an Adequate School Budget,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, December 2, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/educational-equity-requires-an-adequate-school-budget/.

[6] Erin Roth and Will Perkins, “D.C. Schools Shortchange At-Risk Students,” June 26, 2019, Office of the District of Columbia Auditor, http://dcauditor.org/report/d-c-schools-shortchange-at-risk-students/.

[7] Alyssa Noth. December 2, 2019.

[8] “2020 GAO District of Columbia Public Schools,” Office of the Chief Financial Officer, July 25, 2019, https://cfo.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/ocfo/publication/attachments/ga_dcps_chapter_2020j.pdf

[9] “Learn the Process & Analyze the Data,” District of Columbia Public Schools, https://www.dcpsdatacenter.com/budget_process.html.

[10] Stephanie Farmer and Ashley Baber, “Student Based Budgeting Concentrates Low Budget Schools in Chicago’s Black Neighborhoods,” Project for Middle Class Renewal, September 23, 2019, http://publish.illinois.edu/projectformiddleclassrenewal/files/2019/09/Student-Based-Budgeting-report.pdf.

[11] DCPS Budget, DC Code 38-2907.01(a)(2), https://code.dccouncil.us/dc/council/code/sections/38-2907.01.html.

[12] Author’s calculations based on FY19 submitted budgets compared to FY20 submitted budgets, “Updated 4.23 School Budget Worksheets,” District of Columbia Public Schools Data Center, https://www.dcpsdatacenter.com/.

[13] DCPS Budget, DC Code 38-2905.01(a)(3), https://code.dccouncil.us/dc/council/code/sections/38-2907.01.html.

[14] Erin Roth and Will Perkins.

[15] “School Budget Development Guide Fiscal Year 2020 FY20, District of Columbia Public Schools, February 2019, http://www.dcpsschoolbudgetguide.com/fy20_budget_guide.pdf.

[16] An English Learner (EL) student is defined as a linguistically and culturally diverse (LCD) student who has an overall English Language Proficiency (ELP) level of 1-4 on the ACCESS for ELLs 2.0™ test administered each year.