Support for this research comes from the Abell Foundation and The Partnership to End Homelessness, an impact initiative of the Greater Washington Community Foundation.

Permanent Supportive Housing Is the Key to Ending Chronic Homelessness

DC has one of the highest rates of homelessness in the country, with 65.8 out of every 10,000 residents experiencing homelessness. Eight in 10 individuals who experience homelessness are Black, and nearly experience “chronic homelessness.” While factors such as mental illness or involvement with the carceral system contribute to an individual’s likelihood of experiencing homelessness, a community’s rate of homelessness is driven by housing market conditions.

DC committed to ending chronic homelessness in Homeward DC 2.0, its Strategic Plan to End Homelessness. The single most important step the District laid out in that plan is to expand Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH). PSH—a nationally recognized best practice—combines rental assistance with supportive services for an unrestricted period of time.

Despite the release of Homeward DC 2.0 in fiscal year (FY) 2021, DC has fallen behind, and despite recent major investments in PSH, the District is failing to get people housed in a timely way. By following through on its commitments and investing enough in proven strategies such as improving services and speeding up the leasing process, DC can be the first major city to end chronic homelessness.

The Cost of Ending Chronic Homelessness

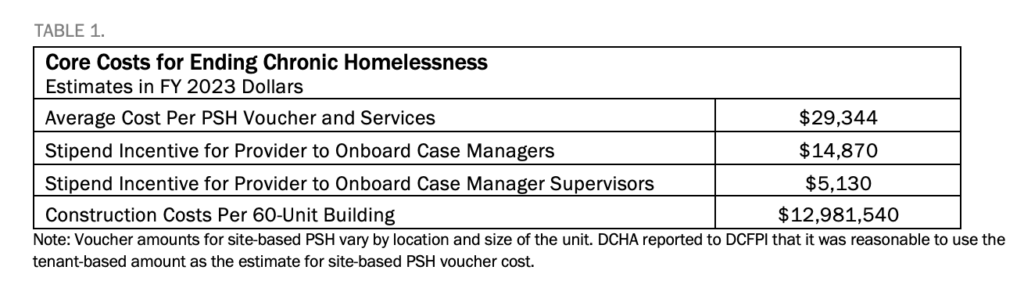

Cumulatively, it will cost the District about $770 million to end chronic homelessness by 2030. At that point, turnover from existing PSH is projected to meet the need of those newly experiencing homelessness, according to DCFPI’s projections informed largely by Homeward DC 2.0. The DC Fiscal Policy Institute’s (DCFPI) estimate reflects the cumulative costs associated with expanding site-based and tenant-based PSH to both end chronic homelessness and address the inflow of residents newly in need, including vouchers, construction costs, and incentive stipends for providers (Table 1).

With Medicaid newly covering many PSH services, the District stands to save approximately $11 million annually starting this year. Lawmakers should reallocate those dollars into the homeless services system to help end chronic homelessness and make improvements to services.

Lessons from Lived Experiences of Unhoused Residents and Case Managers

Rising rents, inadequate eviction prevention assistance, insufficient or delayed investments in new vouchers, and continued implementation challenges related to the low supply of case managers are just a few of the factors that could keep DC from ending chronic homelessness by FY 2030. DC policymakers must address systems challenges that threaten progress.

Between the summer and fall of 2022, DCFPI held eight focus groups of individuals who previously experienced or are currently experiencing homelessness, peer educators, PSH case managers, and other experts in DC to seek their insight on program and policy improvements. DCFPI used this input to develop recommendations for DC policymakers, which include:

- Speeding Up the Leasing Process: DC should launch a 100-day bootcamp to identify and solve problems, ensure the DC Housing Authority conducts inspections promptly, and provide transportation so clients can view units quickly.

- Strengthening Case Management and Supply of Case Managers: DC should increase the supply of case managers and strengthen case management by improving training and coordination between PSH case managers and day program, outreach, and shelter case managers. The Department of Human Services and providers should work together to create peer learning opportunities. Information sharing with clients also needs improvement.

- Improving and Clarifying Rules of Site-Based PSH: DC should solicit client feedback on the design of PSH sites to ensure the sites address their needs and concerns, as well as mandate training for property management staff who interact with clients and help develop and implement building rules.

- Addressing Behavioral Health Needs and Preventing Inflow into Homelessness: DC can expand and strengthen the Department of Behavioral Health’s housing programs to ensure clients don’t have to first become homeless to receive PSH housing, as well as increase the number of psychiatric beds and provide services to residents with traumatic brain injuries.

- Addressing the Needs of an Aging Population: The District should explore whether it can address the concerns that nursing homes and assisted living facilities raised about accepting individuals experiencing homelessness. If not, the District will need to create dedicated facilities for older individuals experiencing homelessness. The District should raise the personal need allowance (the amount of income Medicaid recipients in assisted living facilities are allowed to keep to cover the monthly costs of needs not covered by the facility, such as medication copays, toiletries, and clothing).