Recent changes to school budgeting practices made by the District’s leaders are obscuring the level of funding needed to keep up with growing educational expenses from enrollment growth, inflation, and rising teacher expenses. This has resulted in inadequate funding increases for one of the most important roles of DC government—educating our children—and a budget that in two of the last three years has failed to keep up with rising teacher costs. The absence of estimates of rising educational costs is also a step backward in transparency, making it challenging for parents and other stakeholders to assess the school budget each year. Given these problems, the District should take steps to estimate and publicize information on how educational costs are changing.

The District has a tool to estimate how much it would cost in the coming year to fund current programs and services—the Current Services Funding Level (CSFL) prepared every fall by the Chief Financial Officer (CFO)—but in recent years the CSFL has included nearly every part of the District budget except for public schools and public charter schools. The CSFL, or “baseline,” is a neutral benchmark that measures the fiscal impact of a budget proposal or policy change relative to the status quo. Failing to develop a CSFL for DC Public Schools (DCPS) and DC Public Charter Schools (DCPCS) is a departure from historical practice and best practices.

The decision to stop developing a CSFL for schools appears to reflect a lack of support among elected officials. In 2009, DC’s leaders eliminated a requirement for inflation adjustments to the Uniform Per Pupil Funding Formula (UPSFF), the main tool for funding schools. While DC law requires the Mayor to submit an “algorithm” to the Council to explain the specific factors and methodology she uses to determine proposed changes in the UPSFF, the details in recent years have been thin and included considerations beyond growing costs and need, such as revenue availability and other budget priorities.[1]

The Mayor also recently removed the CSFL figures from her proposed budget documents across all policy areas, further reducing transparency.

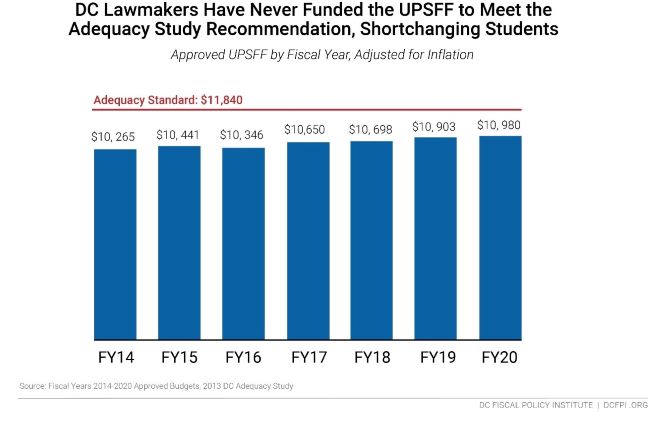

The consequences of failing to fund public schools based on real costs in a transparent manner are harmful: The fiscal year (FY) 2020 per-pupil spending level is $860, or seven percent, below the inflation-adjusted funding level recommended in the 2013 Adequacy Study (Figure 1).[2] Under the pressures of an inadequate budget, DCPS officials are diverting funds meant to provide additional support to students at risk of academic failure to close the gap. [3] This practice continues a cruel cycle where low-income Black and brown students do not get the resources they deserve, and many then leave school unprepared for success in college or career—upholding generations of racial and socioeconomic disparities in outcomes in the District.

The CSFL is essential for budget transparency and accountability because it allows the public to see exactly how the budget works and then hold elected officials accountable for those changes. DC lawmakers should improve current budgeting practices and increase transparency and accountability at the front end of the school budget process by strengthening the CSFL process and making sure current service budget estimates are included in budget documents. This is how it can be done:

The CSFL is essential for budget transparency and accountability because it allows the public to see exactly how the budget works and then hold elected officials accountable for those changes. DC lawmakers should improve current budgeting practices and increase transparency and accountability at the front end of the school budget process by strengthening the CSFL process and making sure current service budget estimates are included in budget documents. This is how it can be done:

- Requiring the CFO to develop an annual CSFL for the DCPS and DCPCS budgets. The CSFL should use the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation measure to project increased costs for non-personnel expenses and the Employment Cost Index (ECI) inflation measure to project increased costs for personnel expenses, plus account for any contractual increases to teacher compensation going into effect. The CFO should work with the Office of the State Superintendent (OSSE) to factor in UPSFF weight adjustments and enrollment projections, and they should publish a detailed accounting on the methods used to calculate the total CSFL.

- Requiring the Mayor to notify the DC Council if the economic assumptions and/or factors that she uses to determine her proposed UPSFF base level differ from those the CFO used to construct the CSFL budget. The Mayor should include this notification in the “UPSFF Foundation Level Algorithm” letter that she is required to submit to the DC Council each year, and she should explain why the difference(s) occurred and detail the specific changes in assumptions and projected costs.

- Encouraging the Mayor to use the CSFL as her starting point when building a new budget proposal. The Mayor should use the CSFL as a guide when developing her budget to better ensure that the proposed changes are based on real costs.

- Requiring the Mayor and City Council to include the CSFL in agency chapters of their budget documents. Including current services estimates with a proposed budget would increase transparency by reducing the need to search through multiple documents needed to make year-to-year comparisons and hold policymakers accountable.

Efforts to estimate needed changes to school funding from year to year is a complement to DCFPI’s recommendation to require the Deputy Mayor of Education to fully reexamine the cost of providing an adequate education (i.e., to recalculate the UPSFF) every five years.[4]

Current Services Budgeting Raises the Bar, Shows What’s Needed to Keep Up

Current services budgeting is common across the nation – the federal government and nearly 50 percent of states practice it in some form.[5] A current services budget estimates how much spending is needed in the coming year to provide the same level of recurring government services and programs provided in the current year, excluding the impact of any new policy decisions.[6] Typically, current services budgets reflect factors such as inflation, employee costs, and population shifts, such as public student or Medicaid enrollment growth.

A current services budget is a valuable tool that can provide policymakers and the public a true assessment of a state’s fiscal health.[7] Policymakers can use a current services budget alongside revenue forecasts to gauge whether there will be enough funding to support programs and services at existing levels or if they will have to increase revenues or cut services. Current services budgeting also helps facilitate budget transparency and political accountability by allowing policymakers and the public to see what the budget is currently funding and whether a budget proposal for the upcoming year would reduce, keep flat, or expand services.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, one of the nation’s foremost thinktanks on fiscal policy, a current services budget is robust and meaningful when it:

- Reflects current, full-year costs of programs and services. Calculations must be adjusted by removing any one-time costs and accounting for the phasing out or ending of a program. Calculations should reflect changes required by previously adopted laws but not any potential new policy decisions. These steps help ensure the baseline is an honest reflection of current levels of expenditures.

- Factors in program-specific inflation and population changes. Prices of goods and services across different programs or services increase at varying rates. For example, health care costs typically increase at a rate much higher than general inflation. A good current services budget would account for this difference. It would also account for expected changes in the population being served by a specific program. For instance, a current services budget for public schools would account for projected changes in student enrollment.

- Is published with regular budget documents. Including current services estimates with a proposed budget increases transparency. Everyday people, budget advocates, and other stakeholders can spend less time searching through multiple documents for information they need to make year-to-year comparisons and hold policymakers accountable.

- Makes public and clearly states the assumptions underlying current services estimates. A current services budget is of little value if it does not provide detailed information on the economic, demographic, and other assumptions underlying its estimates.

- Estimates funding needs at the agency and program or service level. The more detailed a current services budget is, the more useful it is. Estimates at the program or service level can give greater context about the magnitude of changes in a proposed budget.

- Projects funding needs beyond a single fiscal year. A current services budget providing spending projections beyond a single year can be a useful tool for long-term financial planning.

The Current Role of the CSFL in DC’s Budget Process

The DC CFO, which is tasked with ensuring “the fiscal and financial stability, accountability and integrity of the Government of the District of Columbia,”[8] plays an important role in the DC budget process. Every fall, the CFO prepares the CSFL to provide an estimate of how much it will cost the District to continue existing levels of services in the next fiscal year. The CFO can choose whether to develop a CSFL for any department and decide which economic assumptions to use when calculating CSFL estimates.

The CSFL is intended to help the Mayor and other policymakers understand, at the start of the budget process, what’s needed to keep up with growing costs and needs.

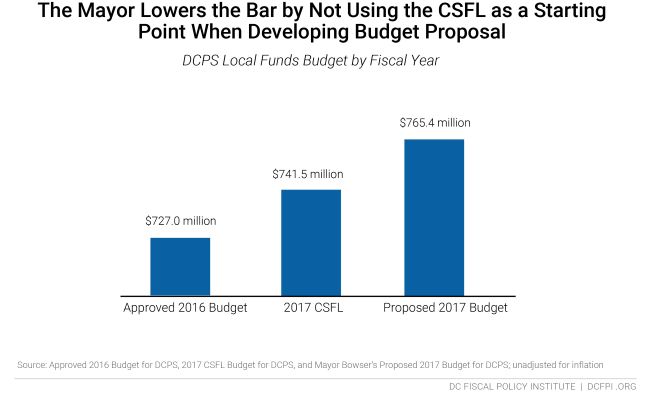

The Mayor’s current process doesn’t utilize the CSFL and instead takes into consideration the prior year’s approved budget, projected revenue availability for the upcoming year, and her overall budget priorities. Not using the CSFL as a starting point can lead to several pitfalls. An approved budget from the current year does not reflect how much it will cost the District to provide current programs and services in the upcoming year, therefore underestimating what’s needed to keep up with the status quo. This process lowers the bar, making it seem as though year-to-year investments are increasing, when in fact they may not even be keeping up with rising costs or may not be growing much beyond rising costs. The fiscal year 2017 budget process—back when the CFO produced a CSFL for the public school systems—illustrates these pitfalls. The Mayor’s proposed budget for DCPS that year was $756.4 million, which was four percent higher than the FY 2016 approved budget but only two percent higher than the CSFL. (Figure 2, pg. 5).

Another change that is out of line with best practices is the Mayor’s recent decision to remove the CSFL from her budget proposals for all agencies. This decision reduces budget transparency, making it more challenging for policymakers and the public to easily assess whether the proposal is adequate to keep up with growing expenses.

Another change that is out of line with best practices is the Mayor’s recent decision to remove the CSFL from her budget proposals for all agencies. This decision reduces budget transparency, making it more challenging for policymakers and the public to easily assess whether the proposal is adequate to keep up with growing expenses.

The Education Budget Process & Harm of Failing to Budget Based on Projected Costs

The District allocates local revenues to DCPS and DCPCS through the UPSFF, which starts with a foundational level dollar amount that is meant to reflect the per-student amount needed to provide general education services, with adjustments for students in different grade levels. The formula also provides additional funding to schools for serving students in special education, English Learners, and students who are considered at-risk of academic failure.

DC law formerly required the Mayor to adjust the foundation amount by at least the average rate of inflation when developing a budget proposal. Policymakers repealed this requirement in 2009; now, the Mayor can use any economic assumption to determine their proposed yearly adjustments to the UPSFF base level. The Mayor’s proposal sets the tone of the budget debate, but the Council has full independence to put forward a UPSFF base level of their own choosing as well. Since 2009, the education budget appears to be built largely around budget constraints—how much revenues are rising and other priorities—rather than on what is really needed.

The Departure from the CSFL in the DC Education Budget Process is a Recent Practice

The CFO’s choice to not create a CSFL for DCPS or DCPCS is a departure from previous practices.[9] In past years, the CFO adjusted each sector’s budget using a “Student Funding Formula Inflation Factor,” described as a factor reflective of “the inflationary costs that are generally associated with educating students” in both sectors.[10] For several years, this inflation factor was two percent, which the CFO applied to the UPSFF base level but did not adjust for student enrollment growth, meaning the CSFL provided some clarity but was an underestimate of what was needed to keep up with growing costs.

The Harm of Not Keeping Up

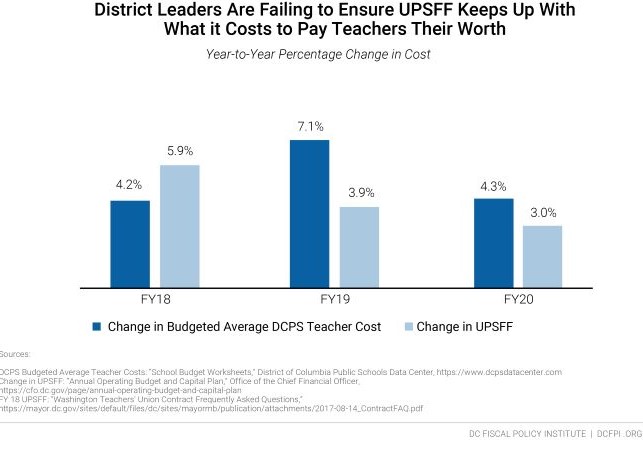

For years, District lawmakers have approved education budgets that failed to provide adequate resources to meet the needs of the students showing up to school eager to learn every day. For much of the last decade (i.e., after lawmakers eliminated the inflation adjustment requirement in 2009), there has been an inconsistent relationship between increases to the UPSFF and the average rate of inflation,[11] and FY 2020 was second time in three years that lawmakers failed to approve a UPSFF that kept up with rising teacher expenses. (Figure 3). When the UPSFF grows slower than inflation and personnel costs, schools effectively face budget cuts. In recent years, these cuts disproportionally affected schools in low-income, Black neighborhoods. In the current school year, 19 schools faced cuts of five percent or more, and 15 of them are in Ward 7 or Ward 8.

This reality, which has been well-documented by the DC Council Budget Office and the DC Council Committee on Education, [12],[13] may have prompted councilmembers to introduce legislation to improve school finance transparency in 2019. It may have also prompted the DC Council to update an existing law to require the Mayor to submit an “algorithm that will be used to determine the next fiscal year’s Formula’s foundation level, which shall include variables for the cost of teachers and other classroom-based personnel and for both school-based and non-school-based administrative personnel.”[14] As noted above, however, Mayor Bowser has not shared detailed information on how her proposed school funding levels have been set.

This reality, which has been well-documented by the DC Council Budget Office and the DC Council Committee on Education, [12],[13] may have prompted councilmembers to introduce legislation to improve school finance transparency in 2019. It may have also prompted the DC Council to update an existing law to require the Mayor to submit an “algorithm that will be used to determine the next fiscal year’s Formula’s foundation level, which shall include variables for the cost of teachers and other classroom-based personnel and for both school-based and non-school-based administrative personnel.”[14] As noted above, however, Mayor Bowser has not shared detailed information on how her proposed school funding levels have been set.

A Better Way Forward: Steps DC Should Take to Budget for the Future

Every child in DC deserves to attend a public school that is adequately funded to keep up with growing costs and needs. The Chief Financial Officer, Mayor, and DC Council can improve the steps they take to move the District toward an education budget that is informed by the real costs of providing an adequate education to every student.

To strengthen budgeting practices that can help policymakers make better choices for the District’s education budget, the following steps should be taken:

- The DC Council and Mayor should require the CFO to develop a CSFL for the DCPS and DCPCS budgets. The CFO should follow historical and best practices by creating a CSFL for both sectors.Going forward, rather than using an across-the-board two percent adjustment, the CSFL and annual adjustments to the UPSFF should take into account that personnel costs grow with the Employment Cost Index (as well as salary increases), while non-personnel costs grow with the Consumer Price Index.The Employment Cost Index (ECI), is a specific measure of changes in costs for compensating workers through wages and fringe benefits, such as health premiums and pensions.[15] ECI tends to grow faster than CPI in part because personnel expenses include health care costs, which are rising far faster than the average prices of consumer goods such as food and transportation. To project increased costs for education-related goods and services, such as classroom supplies and technology, the CFO should use the CPI. The CPI measures changes in prices for a “market basket” of goods and services that reflects average consumption by the U.S. urban population as a whole.If policymakers approved a contractual increase in teacher compensation that will go into effect in the upcoming fiscal year, the added cost should be reflected in the CSFL.Policymakers should require the CFO to work with OSSE to factor in UPSFF weight adjustments and enrollment projections, and they should publish a detailed accounting on the methods and costs used to calculate the total CSFL.The CFO should also update the CSFL to include estimates beyond a single year to strengthen the District’s long-term financial planning process.

- The DC Council should require the Mayor to notify members if the economic assumptions and/or factors that she uses to determine her proposed UPSFF base level differ from those the CFO used to construct the CSFL budget. To date, the Mayor’s methodology for determining proposed increases to the UPSFF base level has been opaque and has included considerations beyond growing cost and need, such as revenue availability and other budget priorities beyond education. To improve transparency, the Council should require the Mayor to explain clearly and in detail any differences between the factors she uses to determine her proposed increases and the factors the CFO uses to develop CSFLs for DCPS and DCPCS. The Mayor should provide this explanation in the “UPSFF Foundation Level Algorithm” letter she is required to submit to the Council each year.

- The Mayor should use the CSFL as a starting point when building a new budget proposal, and the DC Council should jointly use the CSFL and Mayor’s budget as a starting point for its budget. The Mayor should use the CSFL as a guide when developing the budget to better ensure that the proposed changes are based on real costs. Using the approved budget from a current fiscal year to build a new budget for a subsequent fiscal year fails to account for the actual costs of maintaining programs and services at existing levels, which could lead to inadequate funding and budget shortfalls.

- The Mayor and DC Council should include the CSFL in agency chapters of proposed and approved budget documents. Including current services estimates in budget documents increases transparency by reducing the public’s need to search through multiple documents needed to make year-to-year comparisons. It also empowers the public to hold policymakers accountable for their policy and budget decisions.

[1] Letter from Deputy Mayor for Education Paul Kihn to DC Council Chairman Mendelson on Behalf of Mayor Muriel Bowser, “FY 2020 UPSFF Foundation Level Algorithm,” Office of the State Superintendent of Education, January 9, 2019, https://osse.dc.gov/publication/fy-2020-upsff-foundation-level-algorithm.

[2] To learn more about how the District’s funding for the Public School and Public Charter School sectors are inadequate, see: Alyssa Noth, “Educational Equity Requires an Adequate School Budget,” December 2, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/educational-equity-requires-an-adequate-school-budget/.

[3] Alyssa Noth, “The Funding Roadmap for Educational Justice in DC: A Call for Equity Over Equality in DC Public Schools,” December 10, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/the-funding-roadmap-for-educational-justice-in-dc/.

[4] For more details on DCFPI’s recommendation to update the Adequacy Study every five years, see: Alyssa Noth, “Educational Equity Requires an Adequate School Budget,” December 2, 2019, https://www.dcfpi.org/all/educational-equity-requires-an-adequate-school-budget/.

[5] Elizabeth McNichol and Dylan Grundman, “The Current Services Baseline: A Tool for Understanding Budget Choices,” October 21, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/the-current-services-baseline-a-tool-for-understanding-budget-choices.

[6] A current services budget removes one-time funding additions from and restores one-time reductions to the approved budget from a prior fiscal year.

[7] McNichol and Grundman, “The Current Services Baseline: A Tool for Understanding Budget Choices.”

[8] Office of the Chief Financial Officer. “About OCFO,” https://cfo.dc.gov/page/about-ocfo.

[9] Even though the CFO does not prepare a CSFL for DCPS and DCPCS, he does remove one-time costs and restores one-time reductions to each sector’s budget.

[10] Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “FY 2018 Current Services Funding Level Budget.” Oct. 6, 2016.

[11] DC Council, “Committee of the Whole Report on the Bill 22-242, p. 4,” https://ggwash.org/files/B22-242_FY18_Local_Budget_Act_draft_report.pdf.

[12] DC Council, “Committee of the Whole Report on the Bill 22-242”.

[13] The Committee on Education, “Fiscal Year 2020 Committee Budget Report,” May 9, 2019, http://www.davidgrosso.org/grosso-analysis/2019/5/1/draft-report-and-recommendations-of-the-committee-on-education-on-the-fiscal-year-2020-budget-for-agencies-under-its-purview.

[14] D.C. Code § 38–2903(b), https://code.dccouncil.us/dc/council/code/sections/38-2903.html.

[15] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Employment Cost Trends,” United States Department of Labor, https://www.bls.gov/ncs/ect/escalator.htm.