This report is part of a series of research and analysis on how DC can build a tax system that embodies racial justice in both its design and the public investments it provides. Find the full series here.

Nearly a century of racist policies and practices such as racially restrictive covenants and lending discrimination cemented racial disparities in homeownership and home values that are, in turn, drivers of DC’s extreme, persistent, and self-perpetuating racial wealth gap. District lawmakers have begun efforts to address these racial disparities but to succeed, they must address property tax policies that concentrate wealth among the already wealthy while raising revenue for programs that can stabilize housing and create wealth building opportunities for Black residents.

DC provides a substantial number of tax benefits for owner-occupied homes, regardless of the value of the property and, in one case, regardless of the property owners’ income. While well-intentioned, these property tax breaks are not all well-targeted and often benefit wealthy homeowners. By better targeting property tax benefits, the District could free up revenue to expand much-needed programs that help ensure longstanding DC residents, especially multi-generational households and seniors with low and moderate incomes, can stay in their homes in a rapidly gentrifying housing market and pass on those homes to future generations.

Summary:

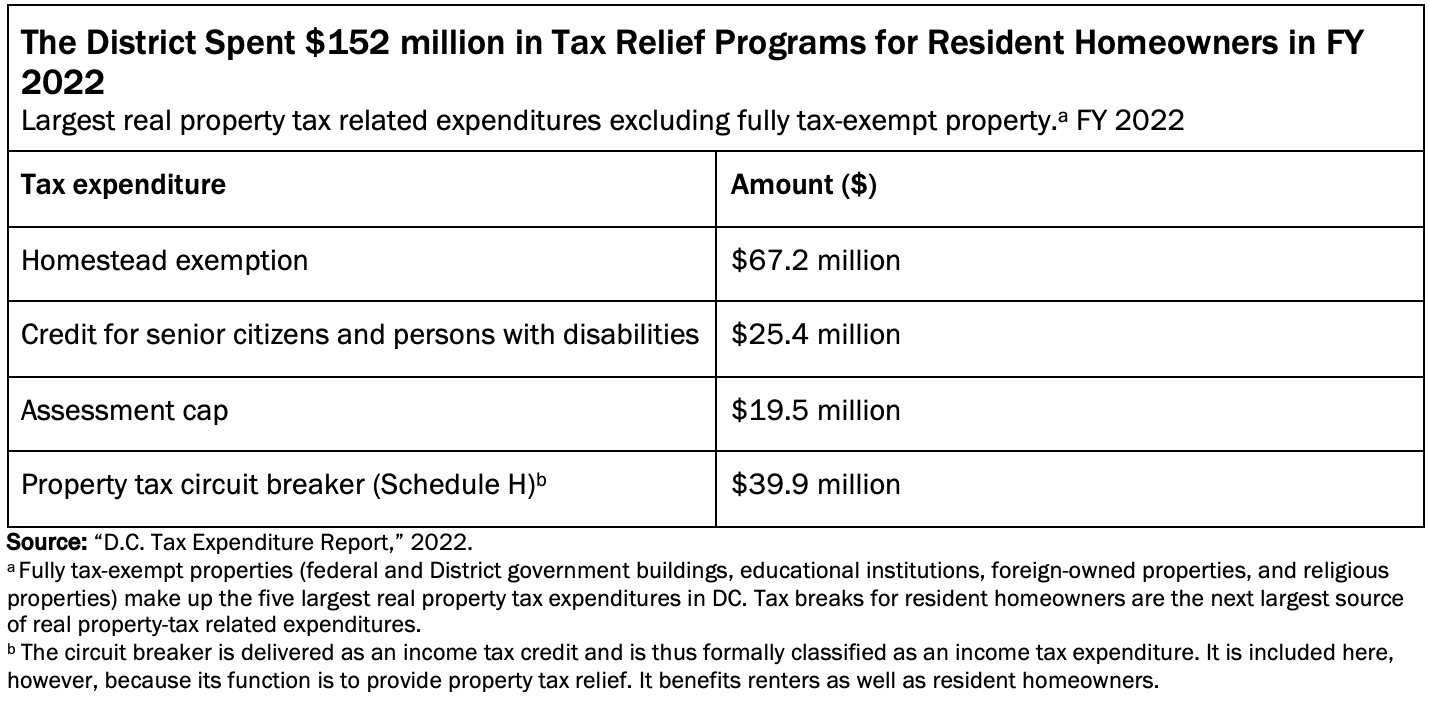

- The District spent $152 million in tax benefit programs for owner-occupied homes in fiscal year 2022.

- DC’s standard homestead deduction, which allows all property owners who live in their home to subtract a certain amount from the full assessed value of their home, has no income requirement or property value cap.

- Eliminating the homestead deduction for properties valued over a certain threshold would better target the homestead tax reduction to Wards with lower home values.

- DC’s assessment caps prevent sharp property tax increases but can create inequities in taxable assessed value across neighborhoods. Eliminating the tighter cap and linking the broader cap to ability to pay would better target low and moderate income homeowners.

- Resident homeowners over age 65 enjoy a very low effective tax rate, even though age itself is not always a good measure of the ability to pay. By better targeting the property tax reduction for seniors, the District can free up revenue to provide more robust support for low-income senior homeowners.

- DC’s property tax circuit breaker is well-targeted to homeowners and renters with low and moderate incomes. By adjusting the circuit breaker’s property tax thresholds for each income band so they are applied incrementally and expanding income eligibility for non-seniors, the District can increase support to homeowners and renters with low and moderate incomes.

DC Has Several Large Property Tax Benefits for Owner-Occupied Properties

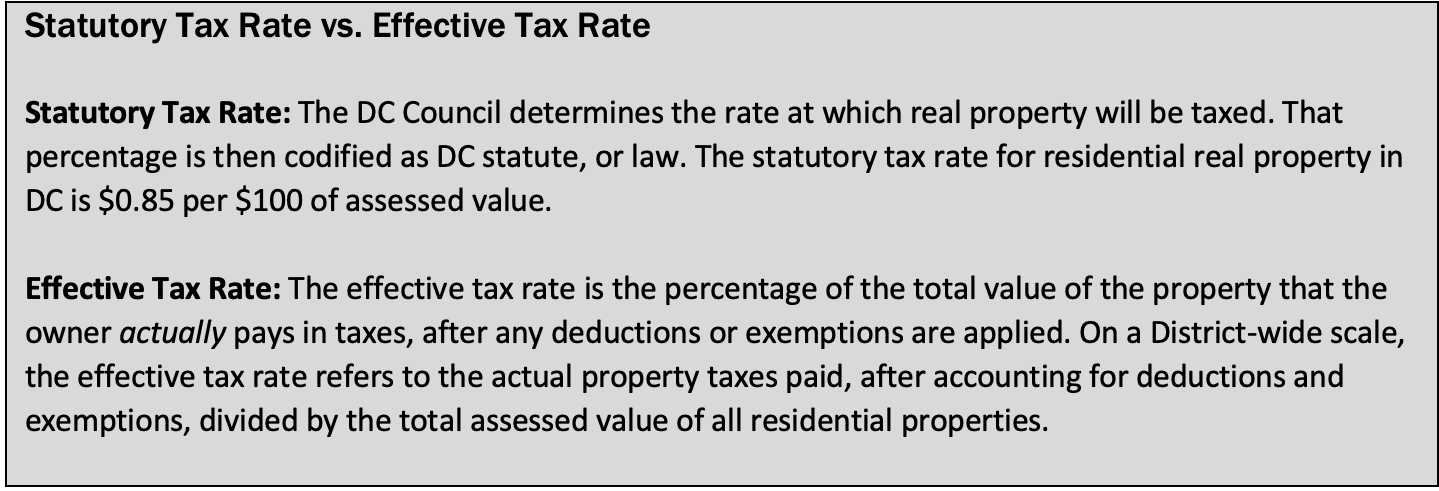

The District currently taxes all residential properties, regardless of value, at the same rate of $0.85 per $100 of taxable assessed value.[1] However, residential property owners do not always pay taxes on the full assessed value of their homes. Instead, they pay based on the taxable assessed value of a home, which may be reduced by one or more of DC’s property tax benefit programs.

DC reduces residential property taxes for property owners who live in their homes and, in one case, for renters through several programs: the homestead deduction, the property tax circuit breaker, a 50 percent property tax reduction for senior citizens and people with disabilities, and a 10 percent assessment cap (2 percent for seniors).

DC’s Homestead Deduction Provides Tax Break to All Resident Homeowners, Including the Wealthy

DC’s largest property tax break, called the homestead deduction, permits all property owners who live in their home, including wealthy homeowners, to subtract a certain amount from the full assessed value of their home and pay tax only on that reduced taxable assessment. In 2023, the homestead deduction is $84,000, translating to a $714 reduction in a property owner’s tax bill.[2] For example, if a homeowner’s home is worth $400,000, DC’s property tax rate of $0.85 per $100 would be applied to the taxable assessment of $316,000.

DC adopted its original homestead deduction in 1978 as a way to encourage home ownership and lessen the tax responsibility of homeowners who live in their homes.[3] The homestead deduction is DC’s largest real property tax expenditure, after accounting for fully tax-exempt properties (Table 1). Due to this deduction, owner-occupied properties in DC enjoyed an effective tax rate of $0.68 per $100 of value in 2022.[4],[5] This lower effective tax rate means that homestead properties contributed just 18.7 percent of real property taxes in 2022, despite accounting for 31.4 percent of real property value in the District.[6] In fiscal year (FY) 2022, the deduction cost DC $67.2 million in foregone revenue.

Homestead deductions provide a greater proportional tax benefit to owners of lower-value properties.[7] For example, exempting $84,000 from taxation represents a 50 percent reduction in taxable value for a home valued at $168,000 but only a 1 percent reduction in value for a $840,000 million home. However, if eligible homeowners with low incomes are less likely to file a homestead application, due to poor internet access or transportation barriers for example, then higher-income groups may disproportionately benefit from this deduction, reducing progressivity.[8],[9]

Additionally, the standard homestead deduction has no income requirement or property value cap. As a result, the District loses revenue each year by giving tax breaks to wealthy homeowners.

Property Tax Circuit Breaker Targets Homeowners and Renters with Low or Moderate Incomes

DC’s property tax circuit breaker, also known as Schedule H for the income tax form required to apply for the credit, operates much like an electrical circuit breaker that cuts off the flow of power when a circuit is overloaded. In this case, it cuts off or reduces property taxes when they’ve become too high relative to household income. [10],[11]

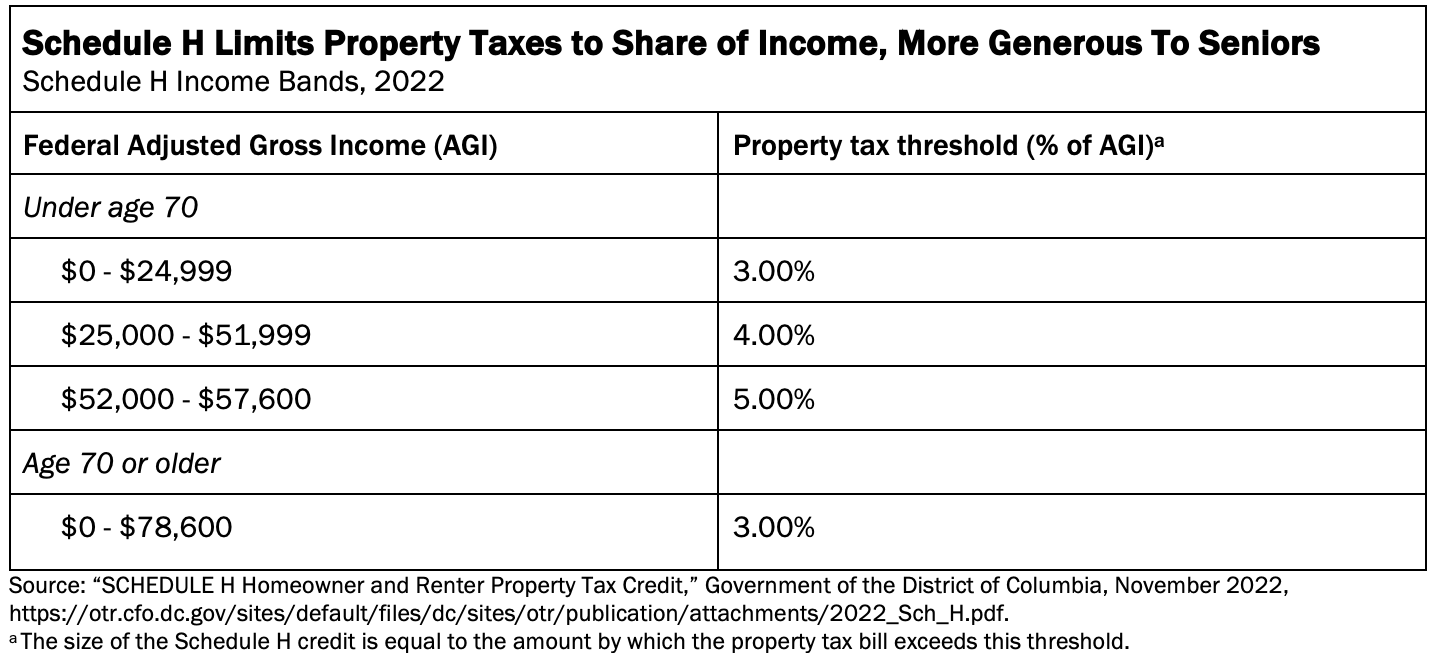

Adopted in 1977, Schedule H is a refundable credit, which means that residents with low or no tax liability still receive a cash refund for any amount by which the credit exceeds their total income tax bill. In tax year 2019, 35,053 taxpayers claimed the credit. Unlike the homestead deduction and other major property tax benefit programs, Schedule H is available both to resident homeowners and renters, who are assumed to pay a portion of DC property taxes in the form of higher rent.[12] Only residents with lower incomes are eligible for the credit: The income limit in 2022 was $57,600 for tax filers under age 70 and $78,600 for tax filers age 70 or older.[13]

For homeowners, the size of the credit is scaled to the amount by which a taxpayer’s property tax bill exceeds a certain percentage of their income with lower-income groups benefiting from lower thresholds (Table 2). For example, a taxpayer whose income is $30,000 per year and whose property tax bill equals 6 percent of their income ($1,800) would receive a credit equal to 2 percent of their income, because the property tax threshold for their income is set at 4 percent. In other words, this taxpayer would receive a property tax credit of $600. The maximum credit in tax year 2022 was $1,250.[14]

DC Seniors Benefit from Effective Tax Rate That Is Less Than Half of Homesteads Where Owner is Not Elderly or Disabled

Resident homeowners, or “homesteaders,” who are either over age 65 or have a disability and whose households have a combined adjusted gross household income of less than $149,400 qualify for a 50 percent reduction in their real property tax liability through the Senior Citizen or Disabled Property Owner Tax Relief program.[15] Because of this program and other age-restricted property tax benefits, homesteads owned by seniors in DC enjoy a very low effective tax rate of $0.33 per $100 of assessed value – less than half that of homesteads where the owner is not elderly or disabled.[16]

DC’s Assessment Caps Prevent Sharp Property Tax Increases For Homeowners in Rapidly Appreciating Neighborhoods

Property owners who meet homestead eligibility criteria also benefit from an annual 10 percent cap on growth in the taxable value of their property, and since 2022, a cap on growth of 2 percent for seniors.[17] The benefit is offered as a credit on a homeowner’s property tax bill rather than a reduction in the actual assessment—in other words, a property cannot be taxed on more than a 10 percent increase in its assessed value (or 2 percent increase for qualifying seniors).

However, there is a limit to how much the cap can constrain a property’s taxable assessment. Taxable value of the property must be at least 40 percent of the property’s full assessed value in the current year. DC adopted the 10 percent assessment limit in 2001 as a way to protect DC residents from quick growth in property tax liability due to rapidly appreciating home values.[18] As of 2018, lower-income seniors and people with disabilities who were eligible for the homestead deduction and the 50 percent property tax reduction benefited from an even more generous growth cap of 5 percent, which the District then further reduced to 2 percent in 2022.[19],[20] To qualify for the more generous assessment cap, seniors and people with disabilities must have an adjusted gross household income of less than $149,400.[21] In tax year 2021, 33,148 owner-occupied households benefited from either the 10 percent or 2 percent assessment cap.[22]

DC Should Better Target its Property Tax Benefits to Address Racial Inequity

DC can better achieve its goals of reducing property taxes for homeowners with financial need and also advance racial equity by scaling back some of its less well-targeted property tax benefits and diverting those funds to expand Schedule H in ways that improve its impact.

Limit the Homestead Deduction

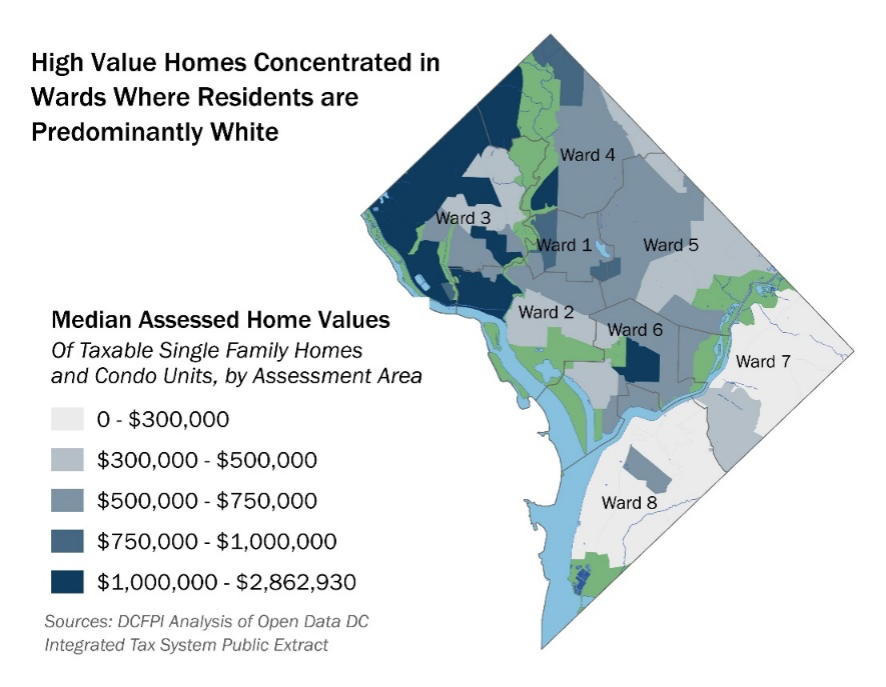

DC can make the homestead deduction program more racially equitable by capping the property value eligible for the deduction to better target the support. This would eliminate the homestead deduction for properties valued over a certain threshold. Racial disparities in both income and intergenerational wealth mean that Black DC residents are less likely to be able to afford to purchase a home in the District and are more likely to live and own homes in wards with fewer high value homes.

If the District imposed a property value cap for the homestead deduction at $1.5 million, it would better target the homestead tax reduction to Wards with lower home values. This way, the program could focus support to residents who, because of the compounding effects of years of racist policy and practice, are unable to build as much wealth through homeownership as residents in whiter, wealthier Wards.

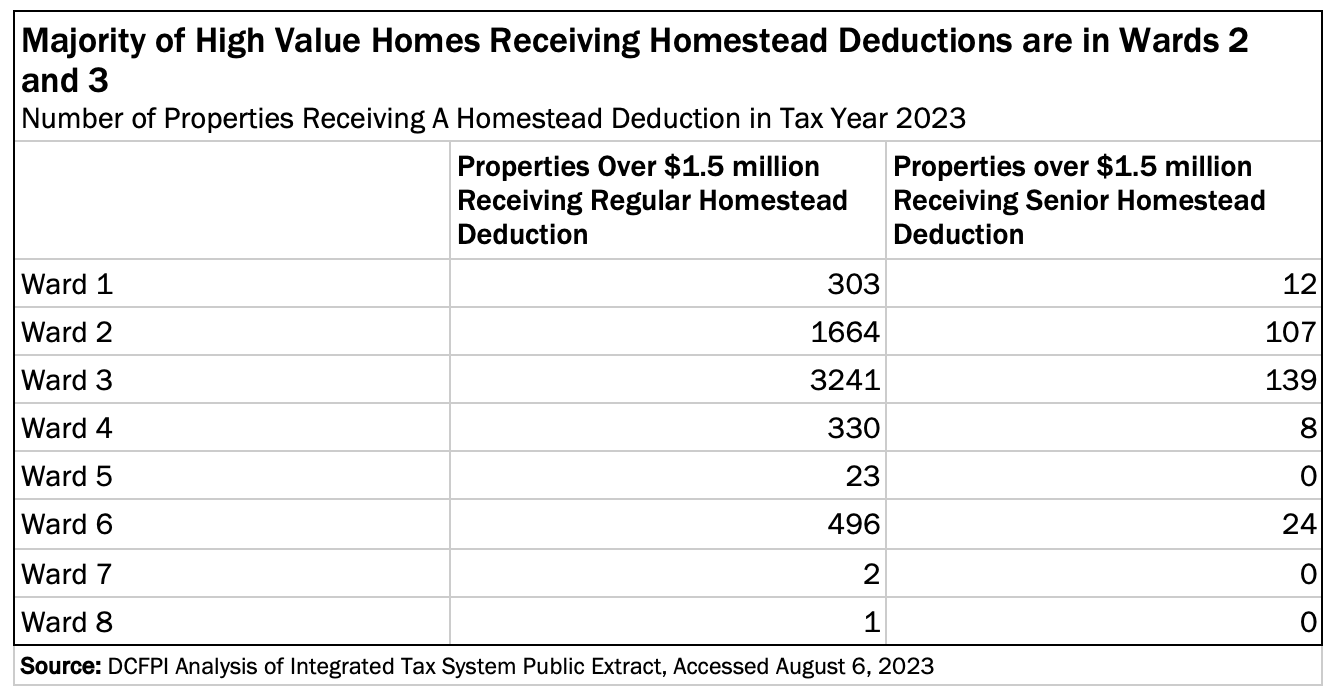

In majority Black Wards 7 and 8, there are a combined total of three homes valued over $1.5 million receiving the homestead deduction. In contrast, in Ward 3, where 82 percent of residents are white, 3,241 homeowners claim the homestead deduction for homes that are valued over $1.5 million. In Ward 2, where the population is 75 percent white, 1,664 high value properties receive the homestead deduction. (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Eliminating the homestead deduction for properties with a taxable assessed value over $1.5 million would have little impact on owners of high value homes and save the District $4.3 million in annual revenue.[23] This savings could then be dedicated to programs that strengthen homeownership among Black and brown households or improve housing stability for residents with low incomes.

Better Target the Property Tax Reduction for Seniors

DC can better target its 50 percent property tax reduction for seniors to need. Age itself is not always a good measure of the ability to pay and the District has better measures of actual need like income and home value.[24] A benefit program based on age or other non-income related criteria will deliver benefits only to a slice of homeowners, capturing some with need but leaving out many others who may struggle with their property taxes given their level of income.[25] Although DC’s senior credit is income-restricted, the program’s income threshold is relatively high and, like the homestead deduction, could be strengthened by capping the value of homes eligible for the reduction. Targeting this program could free up additional funds to provide more robust support for low-income senior homeowners through an expanded Schedule H.

There are 18,496 properties that receive a 50 percent reduction in their property taxes through this program, and 85 percent of them are located in either Ward 2 or 3 where DC’s wealthiest residents live.[26] Of those properties, 290 have a taxable value of over $1.5 million. Moreover, 16 homes valued above $3 million (all in Wards 2 and 3, and with some valued as high as $8.8 million) received this tax reduction in 2023, totaling $281,000 or an average of $17,563 in reduced taxes. Eliminating this deduction for homes valued over $1.5 million would yield $2.4 million in revenue to dedicate to expanding Schedule H for DC’s seniors most in need. [27]

Link 10 Percent Assessment Cap To Owner’s Ability to Pay and End Two Percent Cap

Assessment caps treat similar properties differently, introducing potential for inequities.[28] While they prevent sharp increases in property taxes for homeowners in rapidly appreciating neighborhoods, owners of similar homes in slower-growing neighborhoods pay property tax on the full assessed value of their property. This means that homeowners of properties in areas that are considered “desirable” benefit from this tax discount and also the potential high profit of a sale of their home. Meanwhile, owners of homes in areas with slower value appreciation due to disinvestment and systemic racism may not see the benefit of the cap or similarly high benefits of selling their property.[29] DC’s 2 percent assessment cap for seniors creates even further distortion—greatly suppressing the taxable value and therefore property taxes of some properties because of the age or ability of the resident, while other similar properties potentially in greater need of reduced property taxes shoulder a greater share of property taxes.

While the 2 percent assessment cap for seniors does consider the homeowner’s ability to pay, it is overly restrictive and is estimated to rise in cost rapidly over the next several years.[30] It is most likely not providing additional benefit to low- or moderate-income senior homeowners whose property taxes are already greatly reduced through the homestead deduction, 50 percent property tax reduction, and Schedule H. A more equitable and better targeted approach would be to eliminate the 2 percent cap and target the 10 percent cap to households with .

Expand Schedule H to Better Limit Tax Responsibility of Homeowners with Low and Moderate Incomes

DC’s property tax circuit breaker is the most targeted of its property tax benefits. It should be improved in two ways to better fulfill its primary goal of preventing an “overload” of property taxes as a share of a homeowner’s income. As currently designed, the maximum credit limits how much property owners with low incomes can benefit, particularly when they are in rapidly appreciating properties.

For example, a property owner earning $30,000 whose home in a gentrifying neighborhood is newly assessed at $600,000 in value would owe more than 10 percent (or about $3,100) of their income in property taxes after accounting for the homestead deduction and a maximum circuit breaker credit of $1,250. This is despite the fact that the circuit breaker intends to limit property taxes for a homeowner of this income level to 4 percent of their income. By eliminating the cap on Schedule H, DC could ensure that homeowner actually paid just 4 percent of their income (or $1,200) in property taxes.

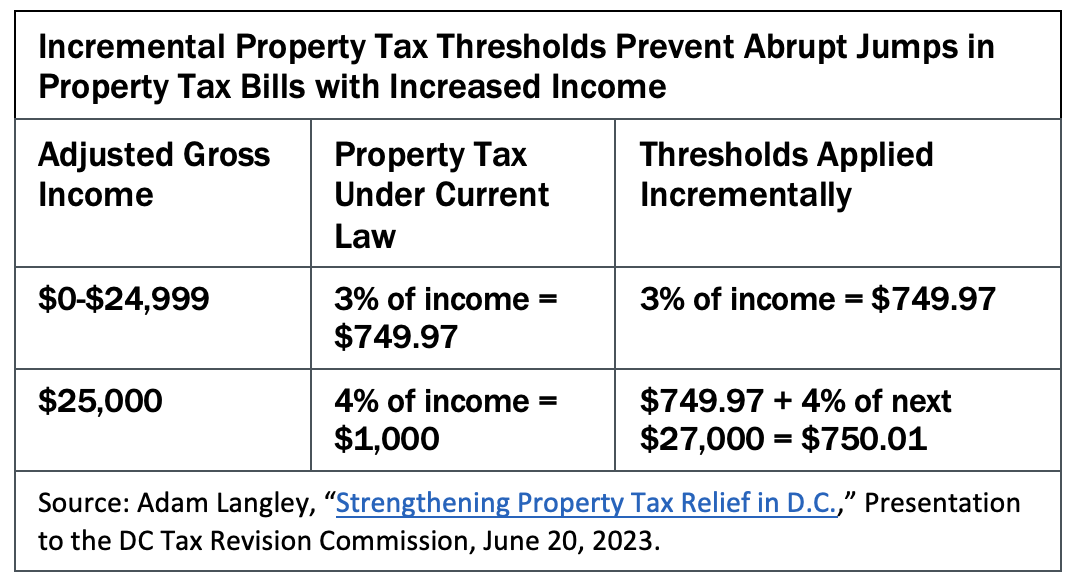

The other key to improving the circuit breaker is to ensure that the property tax thresholds for each income band are applied incrementally. That means that a household with income of $25,000 would pay property taxes equal to 3 percent of their first $24,999 of income and then 4 percent of any amount between $25,000 and $51,999, and then 5 percent of income after that until they’re no longer income-eligible for the credit (Table 4)

A final improvement to the credit would be to expand the income eligibility for non-seniors to equal income eligibility for seniors of $78,600. The current threshold of $57,600 is less than 200 percent of the official poverty line for a two-parent family of four, and a little over half of median household income for the District. Providing support for moderate- and middle-income households struggling to stay in their homes due to rising property assessments and taxes will require raising the income eligibility limit.

[1] For tax year 2022, see table 4-4 in “District of Columbia Data Book,” 2022.

[2] The amount of the exemption changes annually to account for cost-of-living adjustments. See “D.C. Tax Facts,” 2023; and “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[3] For more discussion of the homestead deduction, see “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022; and “Residential property tax relief — Homestead deduction for houses and condominium units,” Code of the District of Columbia § 47–850, accessed July 24, 2023,(hereafter Code of the District of Columbia § 47–850).

[4] For tax year 2022, see table 4-4 in “District of Columbia Data Book,” 2022.

[5] The effective property tax rate is actual property taxes paid after accounting for deductions and exemptions divided by the assessed value of residential properties.

[6] For tax year 2022, see table 4-4 in “District of Columbia Data Book,” 2022.

[7] See Mark Haverman and Terri A. Sexton, “Property Tax Assessment Limits,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, June 2008, (hereafter Haverman and Sexton 2008); and Jon Gorey, “This Simple Policy Tool Can Make Property Taxes Fairer and Ease Homeowner Hardship,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, December 6, 2022.

[8] See Keith Ihlanfeldt and Luke P. Rodgers, “Incomplete Benefit Take-Up, Heterogeneous Assessment, and Property Tax Progressivity,” National Tax Association, 2020, (hereafter Ihlanfeldt and Rodgers, 2020); and Keith Ihlanfeldt, “Property Tax Homestead Exemptions: Explaining the Variance in Non-Claimant Rates Across Neighborhoods,” Florida State University, May 2020, (hereafter Ihlanfeldt, 2020).

[9] See Ihlanfeldt and Rodgers, 2020; and Ihlanfeldt, 2020.

[10] Details on Schedule H are available in “Tax on residents and nonresidents — Credits — Property taxes,” Code of the District of Columbia § 47–1806.06, accessed August 1, 2023, (hereafter Code of the District of Columbia § 47–1806.06) ; as well as “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[11] For more discussion, see “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[12] For the purposes of issuing the credit, DC assumes that property taxes make up 20% of a resident’s rent.

[13] See “District of Columbia Tax Filing Season to Begin on January 23, 2023District of Columbia Tax Filing Season to Begin on January 23, 2023,” Office of Tax and Revenue, DC.gov, accessed August 1, 2023, (hereafter “District of Columbia Tax Filing Season to Begin on January 23, 2023”).

[14] District of Columbia Tax Filing Season to Begin on January 23, 2023 District of Columbia Tax Filing Season to Begin on January 23, 2023.

[15] The income limitation changes annually with a cost-of-living adjustment. See “Homestead/Senior Citizen Deduction,” Office of Tax and Revenue. DC.gov, accessed July 31, 2023; and “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.See “Homestead/Senior Citizen Deduction,” Office of Tax and Revenue. DC.gov, accessed July 31, 2023; and “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[16] For tax year 2022, see Table 4-4 in “District of Columbia Data Book,” 2022.

[17] The assessment increase cap is also sometimes referred to as the residential property tax credit. See more information in “Owner-occupant residential tax credit,” Code of the District of Columbia § 47–864, accessed July 31, 2023; “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022; and David L. Sjoquist, “The Residential Property Tax Credit: An Analysis of the District of Columbia’s Assessment Limitation,” District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission, July 11, 2013, (hereafter Sjoquist, 2013).

[18] See “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022; and Sjoquist, 2013.

[19] See “History of Major Changes in the District of Columbia Tax Structure Fiscal Year 1970 – Fiscal Year 2023” in “D.C. Tax Facts,” 2023; and “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[20] See “Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Support Act of 2022,” D.C. Law 24-167, § 7052 (2022), and “Homestead/Senior Citizen Deduction,” Office of Tax and Revenue, DC.gov, accessed July 31, 2023.

[21] See “Homestead/Senior Citizen Deduction,” Office of Tax and Revenue,” DC.gov, accessed July 31, 2023, and Code of the District of Columbia § 47–863.

[22] See “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022

[23] Based on DCFPI Analysis of data from the Office of Tax and Revenue’s Integrated Tax System Public Extract

[24] See Elizabeth McNichol, “States Should Target Senior Tax Breaks Only to Those Who Need Them, Free up Funds for Investments,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 19, 2019.

[25] John H. Bowman,et al., “Property Tax Circuit Breakers,” LILP, May 2009, (hereafter Bowman, et al., 2009).

[26] Does not include households receiving the Disabled or Veteran Homestead deduction

[27] Based on DCFPI Analysis of data from the Office of Tax and Revenue’s Integrated Tax System Public Extract

[28] Adam H. Langley and Joan Youngman, “Property Tax Relief for Homeowners.” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, November 2021. See more discussion in Sjoquist, 2013; and “District of Columbia Tax Expenditure Report,” 2022.

[29] David L. Sjoquist, “The Residential Property Tax Credit: An Analysis of the District of Columbia’s Assessment Limitation.” Washington, DC: District of Columbia Tax Revision Commission, July 11, 2013..

[30] See DC Tax Revision Commission proposal “Repeal 2 percent property tax assessment cap for seniors.”

[31] Ibid