Chairperson McDuffie and members of the committee, and committee staff, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Shira Markoff, and I am the Director of Economic Policy at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI). DCFPI is a non-profit organization that shapes racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future.

DC’s economy is at its strongest when the workers who power it are the focus of policymaking. Mayor Bowser’s vision for economic development outlined in her budget proposal does just the opposite. It is based on disproven “trickle-down” tactics, prioritizing public money for a stadium and corporate giveaways rather than investing in the people and communities who are the backbone of our economy. DCFPI urges the committee to instead make investments in bottom up and middle out strategies that equitably grow our economy.

In my testimony, I will focus on why the DC Council should:

- Move the RFK stadium deal out of the budget and take the time to have a full public debate on the costs and tradeoffs of the proposed agreement before rushing to seal the deal;

- Pull back on deepening investments in the unproven Housing in Downtown program and require an assessment of the program’s effectiveness;

- Reject ineffective business incentives, such as the Qualified High Technology Companies (QHTC) tax incentive and sales tax holidays for restaurants; and,

- Make equitable investments throughout DC, especially East of the River.

Mayor Bowser is Proposing an Inequality Agenda

Just as DC is set to enter a local recession and Congress is advancing historic cuts to health coverage and food assistance, Mayor Bowser is proposing a budget that abandons residents with the fewest resources to fend for themselves in the coming economic downturn. Her budget takes cash assistance, health care coverage, paid leave benefits, and wages from the District’s workers and most vulnerable residents, while promoting an economic development agenda that sinks scarce public dollars into spending that an abundance of research has shown will not grow anything but the profits of corporations and billionaire sports team owners.

At a time of deep economic uncertainty, her agenda fails to embrace policies that grow DC’s economy from the bottom up and middle out, paving the way for worsening inequality. As the council reviews and changes the budget proposal, it should reject public funding for the widely discredited economic strategies discussed in this testimony that distribute resources to the top and instead prioritize communities in need.

Move the RFK Stadium Deal Out of the Budget and Give it a Full Public Debate

The most expensive piece of the mayor’s economic development agenda is RFK stadium and related costs which, by its sheer magnitude, crowds out other potential investments. The mayor wants to fast track the ill-designed deal with the Commanders, but it is not a good deal for DC residents. Rather, it’s an unnecessarily costly subsidy to a billionaire and his wealthy sports team co-owners with little benefit for taxpayers.

The mayor states that the total District investment for the stadium and parking garages is $856 million. The true number is nearly $2.2 billion in direct subsidies and tax breaks to the Commanders through:

- A $500 million subsidy for horizontal infrastructure for the stadium;

- A $356 million subsidy for parking garages;

- An estimated $600 million in virtually free land by giving lucrative development rights for the area around the stadium to the Commanders for $1;

- An estimated $429 million property tax exemption for the stadium and parking garages; and,

- Redirecting an estimated $300 million in sales taxes on tickets, concessions, and merchandise at the stadium toward stadium maintenance rather than District revenue.[1]

Additionally, the team would keep all the revenue from naming rights, sponsorships, and parking despite DC’s massive subsidy of stadium construction and parking facilities. Analysis shows this would be the second highest sports stadium construction subsidy in the US.[2] This means that DC pays while the Commanders get to keep all the money. There is also funding for RFK in the FY 2025 supplemental budget, which siphons money from other capital projects to finance $89 million for a sports complex and $52 million for site work.

The mayor says that the enormous costs are worth it, because the stadium will create jobs and drive development in the area. And she recently released an economic impact analysis touting the benefits. However, the analysis is opaque in terms of its methodology and detailed assumptions. It does not account for the full cost of forgone tax revenue and is vague about to whom the costs and benefits accrue.[3]

The preponderance of research on stadiums indicate that these claimed benefits are vastly overblown. Sports economists widely agree that NFL stadiums “do not generate significant local economic growth” and are “typically just gigantic giveaways to billionaire owners at the expense of taxpayers.”[4],[5] And, such subsidies overwhelmingly transfer public wealth to white men, research shows.[6] This giveaway is particularly egregious since the mayor has said there is not enough money for basic programs and services that DC residents, especially Black and brown residents, rely on.

Many residents, especially native DC residents, want to see the Commanders return to the District. However, the current approach is wrong. The Council should not approve a deal that gives away massive subsidies that crowd out other investments in DC communities and hands over development rights for the land around the stadium, sidelining the local community’s input on priorities for the site. If the Council supports bringing the Commanders back to DC, it should look to models of other cities that have built stadiums without large subsidies. For example, SoFi Stadium in Los Angeles was fully privately financed, both for land and construction. Any deal should minimize or outright eliminate public funding for the stadium and maximize benefits for the community and for District revenue.

The mayor is trying to push this deal through by an artificial July deadline without allowing time for a full public debate. Instead of rushing this deal through as part of the budget, such a massive commitment of District resources should be pulled out of the budget process and given a separate, comprehensive debate where the full costs are identified, a range of options are discussed such as building affordable housing on public land, the tradeoffs are analyzed, and residents have adequate opportunity to weigh in on their priorities for the RFK site. In addition, the DC Council should require team ownership of the stadium in order to collect property taxes on it and direct all taxes collected from RFK development into DC’s general fund; launch a competitive bidding process for the land surrounding the stadium, with a requirement that the buyer pay market-rate leases; and, ensure that all construction within and surrounding the stadium is covered by a project-labor agreement.

Assess the Effectiveness of Housing in Downtown Before Sinking More Money into It

The mayor is proposing deepening investments in unproven subsidies to developers, including the Housing in Downtown (HID) program. HID provides tax abatements and exemptions from Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) requirements to developers to convert office buildings to housing. Her budget calls for continued tax expenditures of $2.5 million in FY 2026 on the program, along with expanding the program’s geographic reach to Georgetown and Mt. Vernon Triangle. In FY 2027, the mayor proposes temporarily cutting the tax abatement cap by $1.8 million (to $5 million from $6.8 million) before the program vastly expands to $41 million in FY 2028.

This increased investment is planned without any assessment of whether the program is meeting its goals or spurring office-to-residential conversions that would not happen absent the subsidy. Tax abatements often go to companies that are already prepared to engage in a particular business activity, subsidizing activity that would have happened anyway and thus wasting public funds. A comprehensive analysis of business incentives for economic development offered by state and local governments found they are often costly but not highly correlated with unemployment or income levels, or with future economic growth.[7] In fact, there is evidence that some DC developers waited on already planned office conversions until the tax abatement program started.[8]

It is noteworthy that the mayor wants to ramp up the unproven HID program, while scrapping other proven initiatives. For example, she proposes zeroing out the Pay Equity Fund (PEF) beginning in fiscal year (FY) 2027, even though research confirms that the PEF benefits child care workers, child care facilities, and families with young children—generating a 23 percent return on investment.[9]

Before authorizing the HID program’s expansion and increased expenditures, the Council should take these steps to ensure effectiveness, control costs, safeguard public investments, and protect tenants:

- Require the mayor to provide proof that the program is effective in generating office-to-housing conversions that would not have happened without the tax abatement;

- Add a clawback provision to safeguard public funds if developers fail to meet affordable housing unit mandates or first source hiring agreements;

- Remove the exemption from TOPA requirements, which deprives potential tenants in converted buildings of the rights that other tenants have; and,

- Sunset the program in FY 2028; the need for conversions is not permanent and neither should the abatements be.

Reject Proposed Ineffective Business Incentives

The mayor’s plan outlines tax incentives and changes intended to support existing DC businesses and attract new businesses. One positive change is pausing the sales tax increase in FY 2026, since low- and moderate-income households pay a larger share of their income in sales taxes than higher income households.[10] Unfortunately, many of her other plans fall short, squandering millions in tax dollars on ineffective incentives. According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), state and local taxes are a relatively small piece of businesses’ expenses, about 1.8 percent on average.[11] And the portion of those expenses offset by tax incentives is even smaller, making it unlikely that taxes are the deciding factor in where businesses choose to locate.[12] More likely, many of these incentives provide tax breaks for activities businesses probably would have done without them.

The mayor proposes reviving the failed and highly criticized Qualified High Technology Companies (QHTC) tax incentive to attract technology companies. These capital gains tax cuts are estimated to cost the city nearly $2.2 million for FY 2026 and FY 2027, increasing to more than $7 million in FY 2028 and FY 2029. The Council largely ended the QHTC in 2020 after the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) found the program to be costly without strong accountability measures or any sign of economic benefits.[13] (Appendix A provides an overview of the CFO’s key findings on the program’s issues.) DC is already home to a booming tech sector due to a highly educated workforce and strong talent pipeline, so this tax incentive is unnecessary and has already proven ineffective. However, if the Council decides to revive this tax incentive, it must first make significant changes to the program to limit the cost, increase effectiveness, and strengthen transparency, as discussed in Appendix A.

The mayor also proposes “sales tax holidays” for restaurants. This proposal would be costly for DC, with more than $2.1 million in lost revenue in FY 2025 and nearly $4.5 million in FY 2026. Research shows that sales tax holidays disproportionately benefit wealthy residents, who can adjust the timing of purchases to coincide with tax breaks. Sales tax holidays also enable businesses to exploit consumers with higher prices. Moreover, they are difficult for both businesses and the government to administer, with businesses having to make complicated changes to their financial systems for a one-day event.[14] The Council should reject this ineffective strategy.

Make Equitable Investments Throughout the District, Especially East of the River

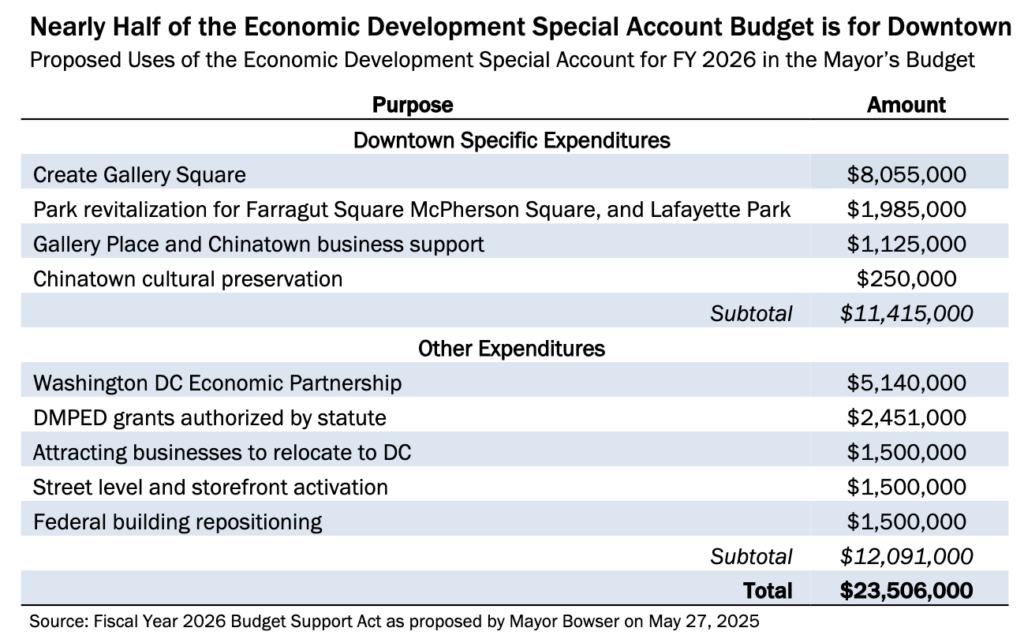

Economic development that creates well-paying jobs for residents and generates revenues for the District is essential for DC’s future, especially given federal layoffs. However, economic development initiatives must be equitable, with a focus on the areas and communities most often sidelined from opportunities, particularly East of the River (EOTR). The mayor’s proposed budget does not meet that standard. For example, nearly half of the proposed uses for the $23.5 million Economic Development Special Account in FY 2026 are for downtown projects—including more than $8 million to create Gallery Square—while none are specifically designated for EOTR (Table 1). The disproportionate focus on downtown threatens to deepen racial and geographic inequities.

Another example of the lack of investment in Black and brown communities in the mayor’s budget is the proposed elimination of the Medical Cannabis Social Equity Fund (SEF). The SEF would provide grants, equity, and loans to legacy cannabis entrepreneurs and communities most directly harmed by cannabis criminalization to facilitate their entry into the medical cannabis market. The mayor’s proposal would result in a loss of $6 million from the SEF over the financial plan.

DC will never achieve transformational growth by doubling down on ineffective, inequitable, and disproven economic development strategies. As the Council reviews and makes changes to the mayor’s budget proposal, DCFPI urges the Council to focus the District’s limited economic development resources on proven strategies rather than squandering revenue, center and support historically marginalized communities, and bring well-paying jobs to DC, especially EOTR.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I am happy to take questions.

Appendix A: Summary of the CFO’s Findings on the QHTC Tax Incentive and Recommendations for Improvements

In 2019, the CFO published a review all DC tax expenditures, including the QHTC tax incentive. The report found that the program was costly, with DC forgoing $184 million in corporate franchise tax revenues from 2001 to 2015, which amounted to 5 percent of the total franchise tax revenue during that time. DC also lost revenue through sales and property tax credits, estimated in the tens of millions of dollars.[15] Moreover, according to the CFO, the incentives were overly generous, since a company could claim tax credits on all its DC income even if only 51 percent of its activities were high technology activities. This was especially beneficial to large companies that had both QHTC and non-QHTC activities.[16]

Overall, the CFO found the program to be broad and not targeted toward bringing high tech businesses to DC or encouraging DC businesses to take on new or additional economic activities. The broad design of the incentives along with a lack of data made it impossible to be able to attribute economic growth to the program or to know what economic activity would not have happened absent the incentives. As the CFO stated, “The QHTC tax incentives may have induced some companies to make new investments in D.C.’s economy, yet they also amount to tax breaks for existing companies with no subsequent new investments.”[17]

The key findings in the report were:

- Through 2015, 24 companies already in DC prior to becoming a QHTC received more than $100 million in tax credits.

- The business that claimed the largest tax credit in one year moved out of DC the next year.

- On average from 2001-2015, just 4 percent of companies received over 54 percent of the credits, while 82 percent received only 17 percent of the credits.

- Many companies claiming the incentives were headquartered outside DC, often in northern Virginia, but kept a small operation in DC or had employees assigned to work in DC-based federal agencies.

- QHTCs were not required to fill jobs for which they claimed tax credits with DC residents, and data was not available to know what percentage of employees were in fact DC residents.

- The program had several fiscal risks for DC, including no cap on the tax credits QHTCs could claim and no requirement that companies pay back credits if they left DC, meaning that DC would have lost revenue from the incentives without receiving the full economic benefits. [18]

The CFO also found that the QHTC tax incentive lacked transparency and accountability. Confidentiality rules prevented disclosure of which companies received QHTC incentives and the amounts. In addition, since no agency was in charge of administering the program, there was limited data collected to help assess the effectiveness of the program. Also, having companies self-certify their QHTC status put the onus on the Office of Tax and Revenue to disprove eligibility.

If the Council decides to revive this credit, the law must address the issues cited by the CFO, and the Council should produce evidence that this tax break is needed to support DC’s economy and already growing technology sector before approving its return. Drawing from the CFO’s findings and recommendations, DCFPI also recommends the following if Council moves the proposal forward:[19]

- Target subsidies to companies that are new to DC or significantly expanding their business activities.

- Cap the subsidy amounts. The CFO recommended capping the annual amount a company can receive in tax credits at either $100,000 or $250,000 per firm so that large companies do not receive a disproportionate share of the tax incentives.

- Add clawback provisions. To safeguard public funds, companies should be required to pay back all of the subsidies they received if they leave DC within the first two years of receiving tax breaks. After two years, a decreasing percentage of the subsidy could be repaid.

- Improve transparency and accountability. An agency should be in charge of administering this program, and it should establish performance metrics and collect data to assess performance.

- Update the definition of QHTCs. The QHTC legislation was passed in 2001, and the technology landscape looked very different back then than it does now. The definition of a QHTC used to determine eligibility for incentives should be updated to reflect what constitutes a high technology company in 2025, since now virtually all companies incorporate technology as part of their work.

In addition, the credit should not be retroactive, as currently proposed in the Budget Support Act.

- Hal Connolly, Nick Sementelli, and Alex Baca, “A Commanders stadium at RFK will actually cost taxpayers $6 billion,” Greater Greater Washington, May 1, 2025.

- Ibid.

- CSL International, “New Commanders Stadium & Mixed Use District at RFK: Economic & Fiscal Impact Analysis,” June 2025.

- Clifton B. Parker, “Sports stadiums do not generate significant local economic growth, Stanford expert says,” Standford Report. July 30, 2015.

- Sean Golonka, “Sports economists pan public funding for A’s ballpark deal as ‘standard stadium grift,’” The Nevada Independent, June 4, 2023.

- Good Jobs First, “How Economic Development Subsidies Transfer Public Wealth to White Men,” June 12, 2023.

- Timothy Bartik, “A New Panel Database on Business Incentives for Economic Development Offered by State and Local Governments in the United States,” W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, January 1, 2017.

- Morgan Baskin, “Downtown D.C. Is Still Struggling To Attract Office Workers, New Development,” DCist, July 27, 2023.

- Clive R. Belfield and Owen Schochet, “Early Childhood Educator Pay Equity Fund: Benefits, Costs and Economic Returns,” Mathematica, November 19, 2024.

- Tazra Mitchell and Danielle Hamer, “Tax Injustice: DC’s Richest Residents Pay Lower Taxes than Everyone Else,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 5, 2021.

- Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, “Tax Incentives: Costly for States, Drag on the Nation,” August 14, 2013.

- Amy Lieber, “Revenue Revealed: It’s Time to Amend DC’s Tax Expenditure Programs,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 26, 2019.

- DC Office of Revenue Analysis, “Review of Economic Development Tax Expenditures,” November 2018.

- Marco Guzman, “Sales Tax Holidays: An Ineffective Alternative to Real Sales Tax Reform,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, August 2, 2023.

- DC Office of Revenue Analysis, 2018.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- See Revenue Revealed: It’s Time to Amend DC’s Tax Expenditure Programs for additional details on these recommendations.