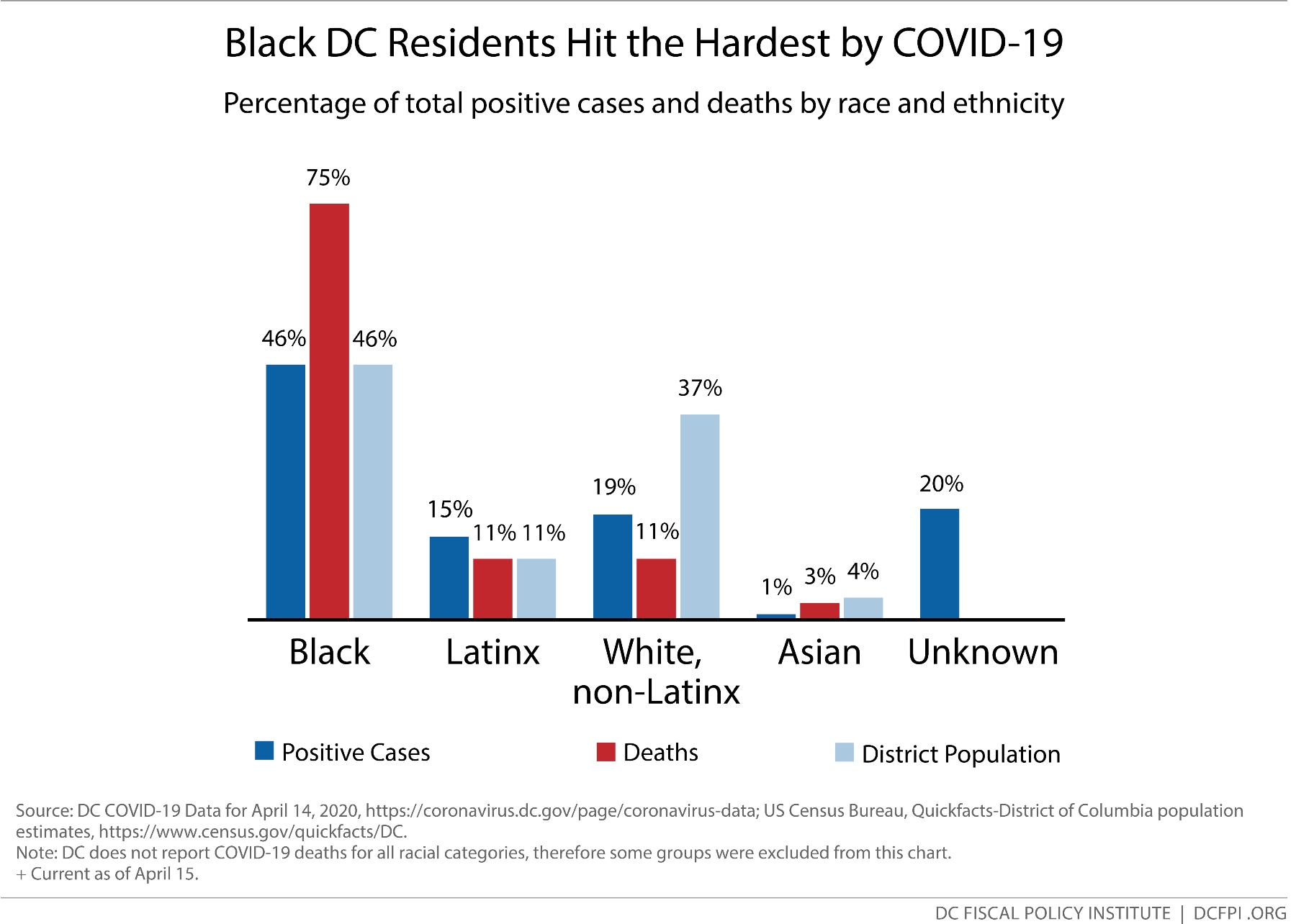

Today, DC Emancipation Day, we commemorate the District’s important position as the first place where federal action freed enslaved Black people. During this global health pandemic, we are reminded of our continued fight to eradicate white supremacy and structural racism’s lethal effects on Black people. In DC, Black residents make up 75 percent of virus-related deaths, and more than twice as many Black residents have tested positive for the virus than white residents (Figure 1). Nearly 20 percent of positive cases by race are unknown, so the impact to Black residents is likely even higher given current trends.

This is not an accident; this is by design. Our Black communities have been neglected by public policy for far too long, and the Mayor and the Council have a responsibility to dismantle the structures and policies that make us most vulnerable.

Anti-Black Racism, Social Determinants of Health, and Medical Bias

Many Black people instinctively knew that the virus would not treat our community fairly. We knew that we would be at greater risk not because we are Black, but because wealth inequality, racism, and deep structural inequities shape our social determinants of health—the physical, social, and economic conditions in which we are born, live, and work. Black people, particularly those who are low-income, are more likely to live in communities where well-paying, stable employment opportunities are far and few, junk food is more prevalent, and the air is polluted.

In DC, over 160,000 mostly Black residents living in Wards 7 and 8 live in food deserts—they are serviced by just three full-service grocery stores with long lines and empty shelves. Ward 3, however, a predominately white area, has nine full-service grocery stores with only about half the population of Wards 7 and 8. This pandemic further exacerbates scarce food options facing Ward 7 and 8 families, forcing them to drive, catch an Uber or Lyft, or rely on already limited public transit to find reliable food outside of their communities. This is but one of many inequities that directly contribute to the underlying health conditions that our brothers and sisters disproportionately suffer from, making DC’s Black residents high risk for becoming gravely ill or dying from the virus.

COVID-19 is also likely torpedoing through Black communities due to our nation’s long history of excluding us from healthcare systems and medically abusing and exploiting Black bodies. Black people are more likely to be uninsured than white people, and even when we can access care, many of us are distrustful of healthcare providers due to the prevalence of racial bias and discrimination we often experience when seeking treatment. Without this proper context, public narratives too often unfairly blame Black people for their own medical oppression and health disparities.

Black People Are DC’s Essential Workers and They Are Risking Their Lives

In order to limit the spread of COVID-19, health officials have encouraged us to reduce contact with others by physical distancing. But distancing is both a privilege and hardship that is not equally shared. Nationwide, less than 30 percent of workers have jobs that allow them to work from home. And due to a long history of racism and occupational segregation, we are among those that are least able to do so. After being used as stolen free labor for centuries, racist policymakers, business owners, and private citizens restricted us to the lowest-paying jobs and most of those occupations were excluded from New Deal labor laws that provided worker protections and benefits. This exclusion and the systemic denial of federally-backed mortgages directly deprived us from opportunities to grow wealth. Today, white household wealth in DC is 81 times higher than that of households from our community, making it harder for us to withstand days and weeks without income during this pandemic.

So, we continue to go to work. In DC, most occupations held by Black workers are those that are deemed essential—cashiers and retail salespersons, janitors and building cleaners, security guards, nurses and home health aides, manual laborers, etc. For many of these essential workers, physical distancing is simply an impossible economic choice that they cannot afford to make—even as access to protective masks and gloves on the job may be limited. And their commute to work is burdened by risks such as reduced public transit services, bringing these essential workers in closer contact with strangers and shared public surfaces. Most of us have experienced the stress and anxiety of biweekly grocery store trips during this pandemic. Now imagine the cumulative stress and anxiety that these essential workers and their families experience traveling to and from work, day after day.

DC Policymakers Must Be Intentional and Innovative to Reduce Disparities

Without intentional acts by the Mayor and Council, this pandemic will drastically exacerbate economic and health inequities in our city. Economists are predicting that millions of jobs nationwide will be lost by summer and if we do policy as usual, this will hurt Black workers the most. Black workers and families in DC still have yet to fully recover from the last recession, so another recession of such a staggering magnitude will be devasting to all of us. And, as Black people continue to show up to work to do their essential jobs in the District, they continue to risk their own and their families’ health and well-being.

The Mayor and members of the Council have called for national and local actions to disrupt racial disparities in COVID-19 health outcomes. Here are a few recommendations that they can take to do so:

- Expand essential duty pay to all essential workers for the critical services that they provide, ensure they have access to protective masks and gloves, and qualify them for priority testing.

- Ensure equitable access to COVID-19 testing in low-income Black neighborhoods.

- Provide anti-racial bias training tools to health care providers to help reduce discriminatory health practices when patients seek care.

- Use racial equity impact assessments to enact policies that proactively disrupt and dismantle traditional inequitable government responses during times of economic recovery.

- Eliminate the ineffective Qualified Supermarket tax incentive and invest the savings in more targeted and permanent grocery store options in Wards 7 and 8.

This is the first in a two-part series focusing on how COVID-19 is affecting Black communities. To read part two, see What Does COVID-19 Mean for the Survival of Black-Owned Businesses?