Chairperson Mendelson and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Tazra Mitchell. I am the policy director at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI), which is a nonprofit organization that promotes budget choices to address DC’s racial and economic inequities through independent research and policy recommendations.

The District has an unprecedented opportunity to leverage American Rescue Plan (ARP) dollars by pairing this federal support with local recurring funds to move toward full funding of the Birth to Three for All DC Act—which is the road map for a better, more resilient early education system. Bold, transformative investments in Birth to Three would boost racial equity and help ensure a just recovery for families and small businesses offering early learning programs.

DCFPI encourages the DC Council to stabilize child care programs and deliver on its promise to ensure that equity begins at birth, as imagined under the Birth to Three for Act. The FY 2022 budget should boost the child care subsidy reimbursement rate with a recurring $60 million investment in each year of the financial plan, as the Under Three DC Coalition is urging. This investment would better position the subsidy rate to cover the true cost of providing great care to infants and toddlers, including ensuring our early educators—most of whom are Black and brown women—are paid fair and living wages on par with their peers in public education.

DCFPI urges the Council to reimagine funding dedicated to child care programs in the approved budget compared to the Mayor’s proposal, which puts zero dollars towards funding the Birth to Three Act. In fact, a sizeable portion of the Birth to Three Act is at risk of elimination without local funding by FY 2023.[1] The DC Council should raise revenue by taxing high income residents—who are undertaxed and have seen their incomes and savings grow over the last year—to sustain recurring investments in higher subsidy rates and deliver on the promise it made in 2018 when approving the law.

DC Council Should Invest in Higher Subsidy Reimbursement Rates

Fully investing in our childcare system is crucial to rebuilding and progressing toward a more equitable city. Child care is a fundamental part of the economy, both in helping parents work and supporting healthy child development. The Child Care Subsidy/Voucher program, administered by Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE), provides families with vouchers that they can use at licensed providers, but the payments to early childhood education providers do not cover the full cost of high-quality care. Inadequate reimbursement makes paying educators what they deserve difficult, and in turn, hampers recruitment and retention of teachers with the qualifications and experience needed to support a young child’s development.

The Birth to Three Act aims to improve the quality of early education by offering competitive compensation for early educators, among other crucial improvements to programs that boost child and parent well-being. Little progress has been made to implement this vision since 2018, with no additional funding provided for DC’s childcare subsidy program in the FY 2021 budget. A recurring $60 million investment would allow OSSE to increase subsidy reimbursement rates to begin to cover the true cost of providing great care to infants and toddlers, including ensuring our early educators are paid fair, living wages.

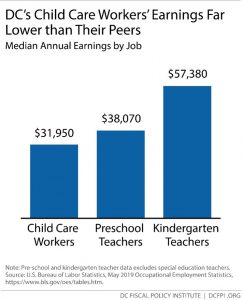

This public investment is crucial: wages for early educators place them among the lowest-paying occupations in the District. In 2019, child care educators in DC had median annual wages of approximately $31,950—or, nearly $15.36 per hour. Preschool teachers with median annual wages fared slightly better at $38,070 per year and kindergarten teachers had median annual wages of $57,380 (Figure 1).

To build parity and respect into compensation for early learning professionals who shape the minds of our infants and toddlers and, ultimately, our city’s future, the $60 million in local funds must be recurring. And, because nearly all ECE workers in the District are women, and a majority are Black or brown, raising educator pay is also a matter of racial and gender equity. This partly reflects a long history in the U.S. of low pay for occupations dominated by women, including jobs working with children.[2]

Tax Justice Can Help Sustain Transformative, Local Investments in Child Care Programs

Tax policy is our key tool to ensure adequate revenue to realize the promise of the Birth to Three Act and meet growing needs so all DC children and early educators can thrive long-term. The District should enact a tax increase on taxable income of more than $250,000. This would raise taxes on just 3 percent of taxpayers in the District, and more than 90 percent of the tax increase would be paid by those earning about a million dollars or more,[3] taking up just a fraction of their recent increase in wealth.

This would raise revenue and make our tax system fairer. We currently have a District tax system where the richest 20 percent of residents pay less in taxes as a share of income than the bottom 80 percent.[4] Because white residents account for the vast majority of DC’s richest residents, undertaxing residents at the top privileges white residents and white wealth—and this comes at the expense of public investments, like the Birth to Three Act’s programs, in underserved communities that advance racial justice.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify.

[1] DCFPI’s interpretation of the DC Council Budget Office’s “Council Rule 736,” memo to DC Councilmembers, dated May 19, 2021.

[2] Paula England, Michelle Budig, and Nancy Folbre, “Wage of Virtue: The Relative Pay of Care Work,” Social Problems, Vol. 49, No. 4 (November 2002), pp. 455-473.

[3] Special data request to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 2021.

[4] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, update to Who Pays?, 6th edition, provided January 2021.