Chairperson Frumin and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to submit written testimony. My name is Tazra Mitchell, and I am the Chief Policy and Strategy Officer at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI). DCFPI shapes racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future.

At a time when poverty reduction is stalled in DC and the price of basic goods is rising, the mayor’s budget proposal for fiscal year (FY) 2026 guts the progress DC has made in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), which plays a key role in ensuring that eligible families with children can meet their needs such as utilities, school clothes, diapers and other hygiene products.[1] Just as DC is set to enter a local recession and Congress is advancing deep cuts to health coverage and food assistance, the mayor’s plan asks those with the least to sacrifice the most to help finance her trickle-down economic agenda.[2]

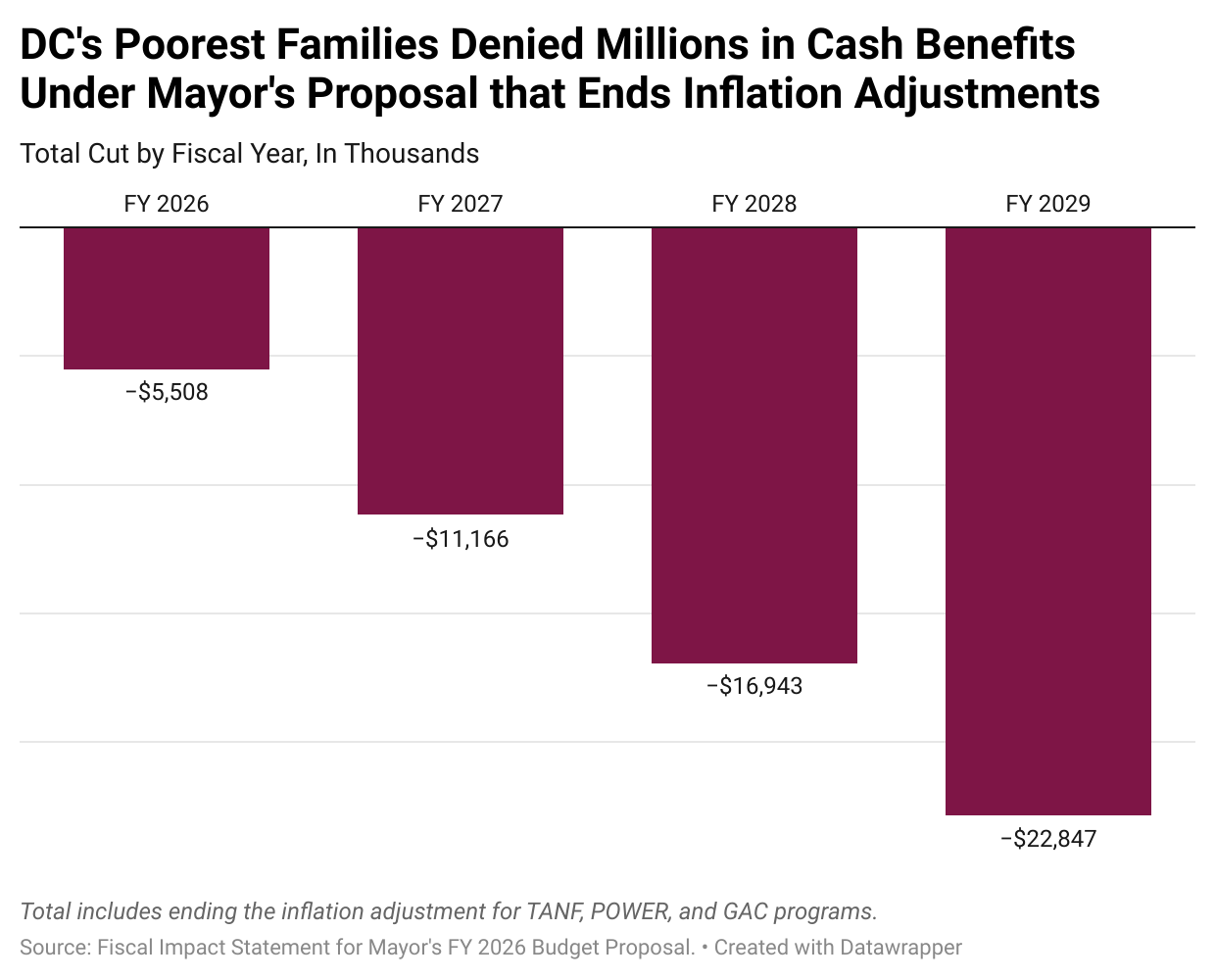

The DC Council should resoundingly reject the mayor’s proposal, which would reduce cash assistance by $130.8 million across the financial plan by:

- Eliminating the program’s annual cost of living adjustment;

- Increasing the penalty for failing to meet a participation requirement for the entire TANF benefit to 25 percent from 6 percent; and,

- Reinstituting penalties for hitting the 60-month time limit for the adult portion of the locally-funded TANF benefit.

Over the years, history has shown that blocking families from assistance to meet their basic needs often puts them on a downward spiral, making it even harder to get back on their feet, and may have long-term negative consequences for children.[3] The Council should reject these punitive changes and continue to treat TANF families with the dignity they deserve.

TANF is a Vital Lifeline to Families Living on the Edge but Has Racist Roots

TANF provides cash assistance, subsidized child care, and employment resources to help families with children living in poverty—primarily those with no other means to meet basic needs. Very few families with low-incomes receive TANF cash assistance: DC’s average monthly caseload was just 13,694 in FY 2024.[4] The program’s benefit levels are extremely low, falling far short of what families need to meet their basic needs, but the help they do provide is critical for helping families when they have very low or no other income. For example, the maximum TANF benefit for a family of three in DC is only 35 percent of the federal poverty level.[5] Some families get less than that amount because of some earnings or punitive policies like sanctions, which reduce benefits for adults who cannot meet work or other requirements.

Cash income enables people to afford the goods and services that help them survive and to live a decent life. For families living on the edge, cash is crucial to providing stability and preventing a downward spiral. They often have few or no assets to lean on in difficult times and need cash for a variety of basic needs: rent and utilities, personal care items such as toothpaste, laundry detergent, diapers, and gas or bus fare, among other things. Also, a family’s needs may change from one month to the next, and because TANF cash assistance provides direct cash rather than specific goods and services (such as a housing voucher), it gives families flexibility to use the income in ways that best help their children.

Moreover, studies have found that income support can help children who are poor succeed over the long term—that is, enable them to do better (and go further) in school, earn more as adults, and even live longer.[6] Thus, TANF cash assistance can open doors of opportunity for the least well-off and should be part of DC’s agenda to grow its economy. Approximately 60 percent of households receiving TANF live in Wards 7 and 8, meaning the very communities that DC has economically neglected the most stand to lose the most under the mayor’s harsh TANF cuts.[7] Local businesses and corner stores in these areas could suffer because residents will have less cash to spend on basic needs.

While Vital, TANF Has A Racist Legacy that the Mayor’s Proposal is Embracing

In addition to setting maximum TANF levels, DC like other states has broad discretion to place restrictions on who can receive cash assistance and whether to apply punitive policies, like time limits and sanctions. Punitive policies in US cash assistance programs stem from a well-documented history of anti-Black racism and warped notion that only some families “deserve” support—from mothers’ pension programs in the early 1900s to Aid to Dependent Children created in 1935 to TANF in 1996.[8]

In an extensive review of the racist legacy of cash assistance programs in the US, experts at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities wrote:

“TANF policies have done more to limit access to the program than to help parents find quality jobs, and they have disproportionately affected Black and brown women, who are far more likely than white women to lose benefits because they were sanctioned for not meeting a program rule or reached a time limit.”[9]

TANF serves a diverse group of families, with some having strong attachment to the labor force and others facing significant personal and family challenges that limit their employment prospects. Justifications for punitive measures ignore the realities of the low-wage labor market, and for some families, the struggle with domestic violence, health issues or depression, and inability to find child care in the absence of presumptive eligibility.[10],[11],[12] Further, there is a preponderance of evidence showing that sanctions don’t increase compliance with work requirements or cut poverty but do increase hardship for adults and children.[13]

For these reasons, the DC TANF Working Group in 2016 recommended reducing punitive measures, which led to DC policymakers using local dollars to eliminate the 60-month time limit and reducing the portion of benefit subject to work sanctions.[14]

Freezing Benefits Will Erode the Value of TANF Benefits for Families

The mayor’s budget eliminates a planned and modest 2.9 percent cost of living adjustment (COLA) for TANF families receiving cash assistance not only in FY 2026 but through FY 2030, even as prices for basic goods and other items continue to grow.[15] This results in a $56.5 million loss in cash benefits across the financial plan (Figure 1). For a family of three receiving the maximum TANF grant, excluding a COLA would cost them $23 a month, or $272 a year in FY 2026. DC made an intentional investment to increase benefit levels after nearly 20 years of flat benefits to improve living standards for TANF families, including big increases in FYs 2017 to 2019 and then standard inflation adjustments in FY 2020 and FYs 2022-2025.[16]

Aligning benefit levels to keep up with inflation is crucial because inflation hits poverty-income families hardest, who spend most or all of their income on necessities, which tend to have greater-than-average inflation rates[17] Again, DC’s TANF benefits remain low compared to the federal poverty line, let alone to the city’s high cost of living, but they do help reduce the depth of poverty. Freezing TANF benefits will place low-income children in more desperate circumstances.

DC Is Improving Work Outcomes Under TANF’s Key Performance Indicators

The mayor’s proposal would increase the penalty on the entire TANF benefit for failing to meet a participation requirement, reducing benefits by $2 million annually. The penalty would increase to a 25 percent cut in benefit size from the current 6 percent cut, which for a family of three receiving the maximum TANF benefit would mean a monthly loss of about $148.

The mayor is proposing to increase work penalties even though data from the Department of Human Services (DHS) show DC is making progress on Key Performance Indicators for work outcomes among TANF families. DHS data show:

- DC increased the monthly average number of new employment placements per 1,000 TANF work-eligible families from 5.1 in FY 2022 to 10.7 in FY 2024. While there were improvements, DC missed its target of 18. DHS explained that “Participation levels in FY 24 were hampered in part due to challenges customers experience in accessing child care specifically for customers residing in wards 7 and 8 close to where they live. The need for non-traditional child care spaces is greater than the available slots and is a barrier for those customers who are employed.”[18]

- DC increased the percent of TANF employment program participants who are engaged in eligible activities from 20 percent in FY 2022 to 22.3 percent in FY 2024. While there were improvements, DC missed its target of 25 percent, but DHS explained that “Customers/providers shared that the emphasis on supporting documentation is burdensome and customers lose interest in participating due to the burden of collecting and submitting paperwork weekly.”[19] DHS committed to making improvements to encourage greater participation moving forward.

- DC excelled at increasing the average monthly number of new education or training placements per 1,000 TANF work-eligible customers from 11.3 in FY 2022 to 43.5 in FY 2024. This far exceeds DHS’s goal of ten for FY 2024.[20]

This suggests that DC’s less punitive approach to TANF is working, but that barriers to affordable child care and burdensome paperwork (and likely others left unmentioned in the DHS report) are holding back greater progress.

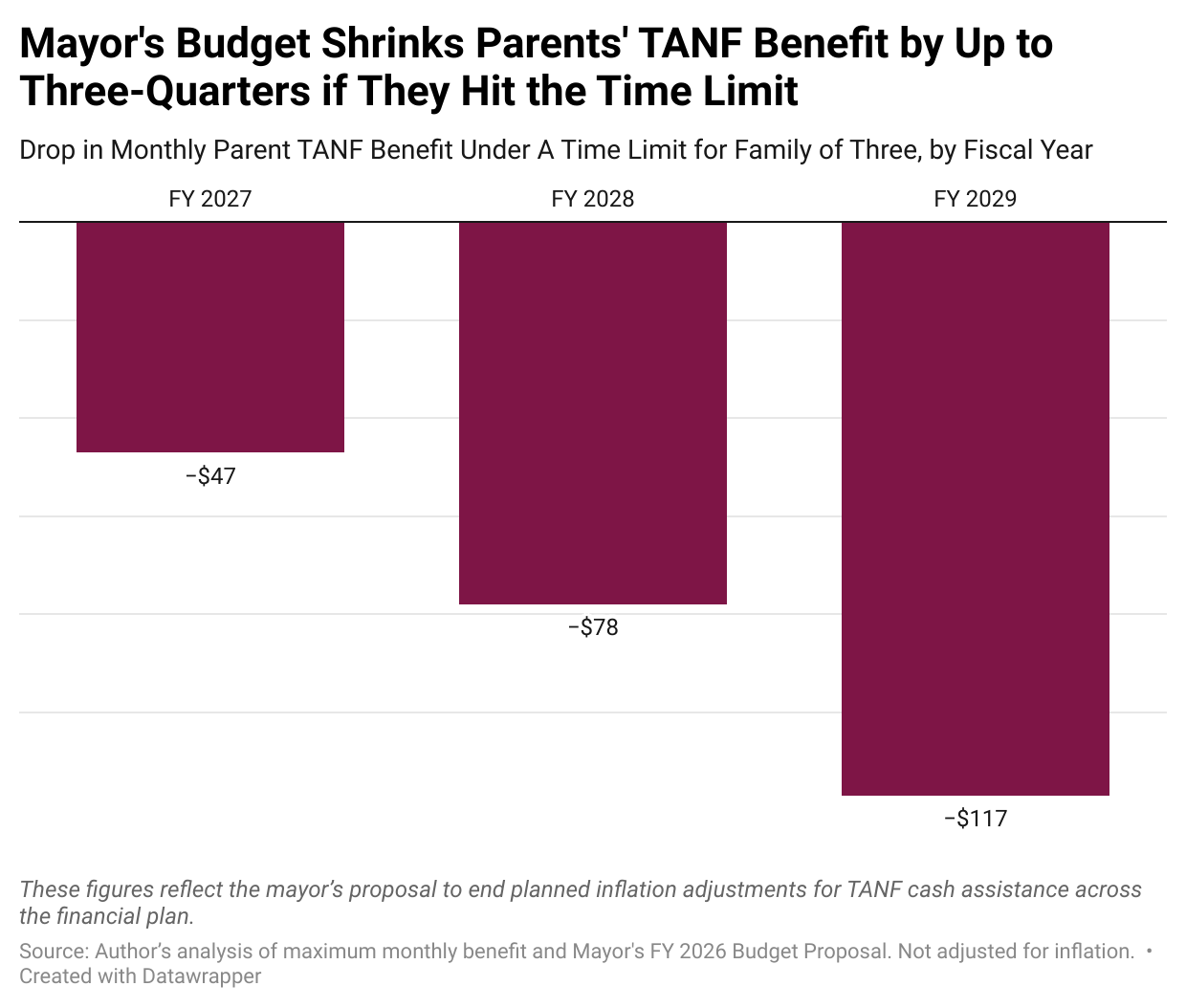

Reinstating TANF Time Limits Will Harm Struggling Families

The DC Council should reject the mayor’s proposal to revive local TANF time limits for adults once they’ve received cash support for five years, or 60 months.[21] Her plan phases in penalties to locally-funded cash benefits for adults hitting this limit: it reduces benefits by 30 percent in FY 2027, 50 percent in FY 2028, and 75 percent in FY 2029 and thereafter. This would deny $66.3 million in cash assistance to low-income families over the financial plan.

In DC, 80 percent of a family’s monthly benefit is designated as the children’s portion and the remaining 20 percent is the parent portion.[22] While only the parent portion would be affected under this proposal, children would still suffer because their overall household budget would become even less adequate. For a family of three, the monthly maximum parent benefit would decline by $47 in FY 2027 to $117 in FY 2029, without accounting for future inflation (Figure 2). It appears the mayor is also proposing a new 25 percent cap on the average monthly number of families that can receive a hardship exemption, such as for acts of sexual abuse and physical injury, from the time limit under locally-funded benefits.[23]

Also, to justify “rightsizing” TANF spending, despite recent intentional efforts to raise benefit levels, the mayor’s administration points out that a portion of local investments in TANF have grown by 48.4 percent in the last five years. However, when accounting for inflation, growth in that portion of local spending drops to 20.1 percent.[24] In addition, the growth in that portion of local spending seems to be driven in part by shifting spending from DC’s “maintenance of effort” (MOE)—a federally required local contribution which can be (but is not exclusively) used to pay for cash assistance.[25] In FY 2023, the local portion of TANF spending in the mayor’s analysis jumps to roughly $85 million from $58 million, a difference of nearly $27 million, but the local MOE drops by a nearly equivalent amount. When looking at both types of local spending together, and adjusting for inflation, DC is investing 5.5 percent less of local dollars in cash and other forms of assistance than it did in 2020.

Before making drastic changes to TANF, DC should hire a consultant to assess how DC spends its TANF funds and make recommendations for how DHS can better align their use of federal and local funds—and, to make recommendations about priorities. DC lawmakers should also interrogate which TANF families will be harmed by the punitive measures, namely those that tend to be more vulnerable. In 2018, the Yale School of Medicine conducted a survey of DC TANF families and found that 60 percent of families screened positive for depressive symptoms indicative of clinical depression, but that families receiving TANF benefits for more than 60 months reported fewer depressive symptoms than those receiving TANF for 60 months or less—suggesting that the lack of time limit is helping them overcome or navigate mental health challenges. At the same time, the survey findings also suggest that those receiving benefits for more than 60 months may do so because they experience more economic precarity, especially in terms of housing—for example, they were less likely to receive housing assistance and more likely to report having experienced homelessness in the previous 12 months.[26]

Neither national research nor evidence from DC justify the mayor’s harsh proposal, which would cause TANF’s reach to plummet, leaving fewer families in poverty with the income support they need to get by. DC can’t fix the economy or grow jobs by making its families poorer.

Thank you for the opportunity to testify, and I am happy to answer any questions you may have.

- Tazra Mitchell, “Poverty Reduction Stalled While Racial and Income Inequality Persisted in 2023,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 16, 2024.

- To learn more about how the mayor’s “growth agenda” relies on trickle-down tactics, see: Tazra Mitchell and Shira Markoff, “Mayor’s Economic Playbook Full of Disproven Ideas that Could Worsen Inequality,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, May 12, 2025.

- LaDonna Pavetti, “Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 7, 2016.

- DC Department of Human Services, “Dept. of Human Services Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF),” accessed June 2025.

- Author’s analysis of maximum DC TANF benefit levels in 2025 compared to the US federal poverty guidelines for 2025.

- Arloc Sherman and Tazra Mitchell, “Economic Security Programs Help Low-Income Children Succeed Over Long Term, Many Studies Find,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 17, 2017.

- Performance Oversight Responses for the Department of Human Services, March 3, 2025, question 171 on page 162/183.

- Ife Floyd et al., “TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 4, 2021.

- Ibid, page 6.

- Floyd et al.

- The 2016 DC TANF Working Group also identified these as common barriers, see: Economic Security Administration, “Recommendations for Development of a TANF Hardship Extension Policy for Washington, DC,” Department of Human Services, October 18, 2016.

- Presumptive eligibility is a policy that allows families to receive temporary and immediate financial assistance to pay for child care services, while the agency administering the subsidy program determines and verifies their eligibility for the program.

- For example, see: LaDonna Pavetti, “Work Requirements Don’t Cut Poverty, Evidence Shows,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 7, 2016.

- Economic Security Administration 2016.

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics, “CPI: Washington-Arlington-Alexandria,” March 2025.

- DC Department of Human Services, “Dept. of Human Services Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF),” accessed June 2025.

- Aparna Jayashankar and Anthony Murphy, “High Inflation Disproportionately Hurts Low-Income Households,” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, January 10, 2023.

- Non-traditional child care may mean night and weekend care but DHS does not offer a definition in this section of the report. Department of Human Services, “FY 2024 Performance Accountability Report,” January 15, 2025, page 15/23.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, page 16/23.

- DC has not had time limits for DC-funded benefits since 2017.

- DC Department of DHS, “TANF State Plan,” Effective October 1, 2023.

- The mayor’s proposal maintains the existing 20 percent hardship exemption for federally-funded benefits.

- DC Department of Human Services, “Dept. of Human Services Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF),” accessed June 2025, page 5.

- Because state MOE funds are not subject to federal time limit restrictions, DC can use those funds to extend cash assistance to families beyond the 60 month federal time limit. To learn more, see: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Temporary Assistance for Needy Families,” March 1, 2022.

- Ashley Clayton et al., “Embracing 2-Gen: Findings from the District of Columbia’s TANF Survey,” Yale School of Medicine, May 2018.