Some unhoused DC residents are rejecting assisted living because of harsh income rules that leave them unable to afford basic items and compromise their quality of life. DC residents who use Medicaid coverage to pay for assisted living must contribute all their monthly income towards the cost of this care, except for a small personal needs allowance (PNA) of $138.[1] This PNA is intended to cover personal expenses not provided by the facility, such as cell phone bills, toiletries, and prescription copays. But the amount is so inadequate that it forces these assisted living residents to go without necessities and leads some individuals to reject assisted living altogether.[2] Black DC residents, who are insured through Medicaid at much higher rates and more likely to experience chronic homelessness than residents of other races because of systemic racism, are disproportionately at risk of being harmed by the PNA policy.[3]

In spring 2025, the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI) interviewed ten DC residents with direct or indirect experience with housing opportunities at Abrams Hall, DC’s only assisted living Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) facility. This facility is intended to provide a deeper level of care needed by individuals who do or have experienced homelessness, and who are often turned away from assisted living facilities because of that experience. But Abrams Hall has suffered from low participation. This is in part because people are unwilling or unable to subsist on the PNA, according to the Abrams Hall provider Housing Up. Interviews helped inform DCFPI’s recommendation for a more adequate PNA level (Appendix I). In July 2025, DC Council added a provision to the fiscal year (FY) 2026 budget that would allocate $500,000 to increase the monthly PNA to $300 if there is revenue growth later in the year. If this revenue growth does not materialize, District leaders should allocate this funding in the FY 2026 supplemental budget and preserve the annual automatic cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) in future budgets so that unhoused DC residents can afford to choose assisted living and meet their basic needs.[4]

Abrams Hall Fills an Unmet Need for Individuals Experiencing Chronic Homelessness Who Are Often Denied Access to Assisted Living

Assisted living is a home-like residential community for older adults and people with disabilities that provides help with tasks, such as bathing and dressing. Residents typically live in a unit but have access to shared living spaces. DC assisted living facilities report a median annual cost of $115,680, or more than seven times higher than the federal poverty level, so affordable coverage is crucial.[5]

Many assisted living facilities will not accept clients who have experienced homelessness and/or have behavioral health conditions.[6] Some facilities have regulations that explicitly exclude individuals with substance use disorders or mental health conditions. Others may deny access because of bias or unwillingness to prescribe or manage medications for behavioral health issues and substance use disorders.[7]

To address the needs of individuals experiencing homelessness or receiving housing and services through the District’s PSH programs, who need deeper levels of care, the District helped fund its first assisted living/PSH facility, Abrams Hall. The facility offers all the services provided by traditional assisted living programs, including meals, medication management, laundry, and house cleaning, as well as a PSH case manager to help connect residents with resources and troubleshoot problems that could lead to eviction. As required by law, this facility subjects all tenants to DC’s monthly $138 PNA.

Low PNA Cited as Primary Reason Abrams Hall is Unable to Fill Slots for its Intended Clientele

Abrams Hall has had difficulty filling its open units. When it opened in September 2022, it could only fill 22 of its 54 units with individuals who had experienced homelessness.[8] Currently, only nine units are occupied by previously unhoused individuals, as the others have died, moved out of state, or left the program for another reason.[9] Due to low participation, DC opened eligibility for the remaining units to seniors with low incomes who have not experienced homelessness.

The provider, Housing Up, cites the low PNA as a primary reason why people are unwilling to accept a placement at Abrams Hall.[10] Individuals with a PSH voucher reported to Housing Up that they would prefer to stay in their current placement, and unhoused individuals reported they would wait for a PSH placement because PSH leaves them with more disposable income at the end of the month compared to the PNA. DC’s PSH program only requires residents to contribute 30 percent of their income towards rent and utilities.[11] For example, a PSH resident may receive Supplemental Security Income (SSI), benefits for those with limited income and assets who are also over 65 or have a qualifying disability.[12] An individual receiving the maximum monthly SSI benefit of $967 would pay $290 in rent and retain $677 to meet their other basic needs—that is about 5.75 times higher than the monthly PNA.[13]

Residents who stay in PSH, rather than moving into assisted living, are likely to struggle with activities of daily living like showering and cleaning, as PSH does not offer the intensity and types of services provided by assisted living. Other residents may be stuck in shelter or sleeping outside, struggling to receive needed services like medical treatment or counseling.

The Low PNA Forces People to Choose Between Necessities

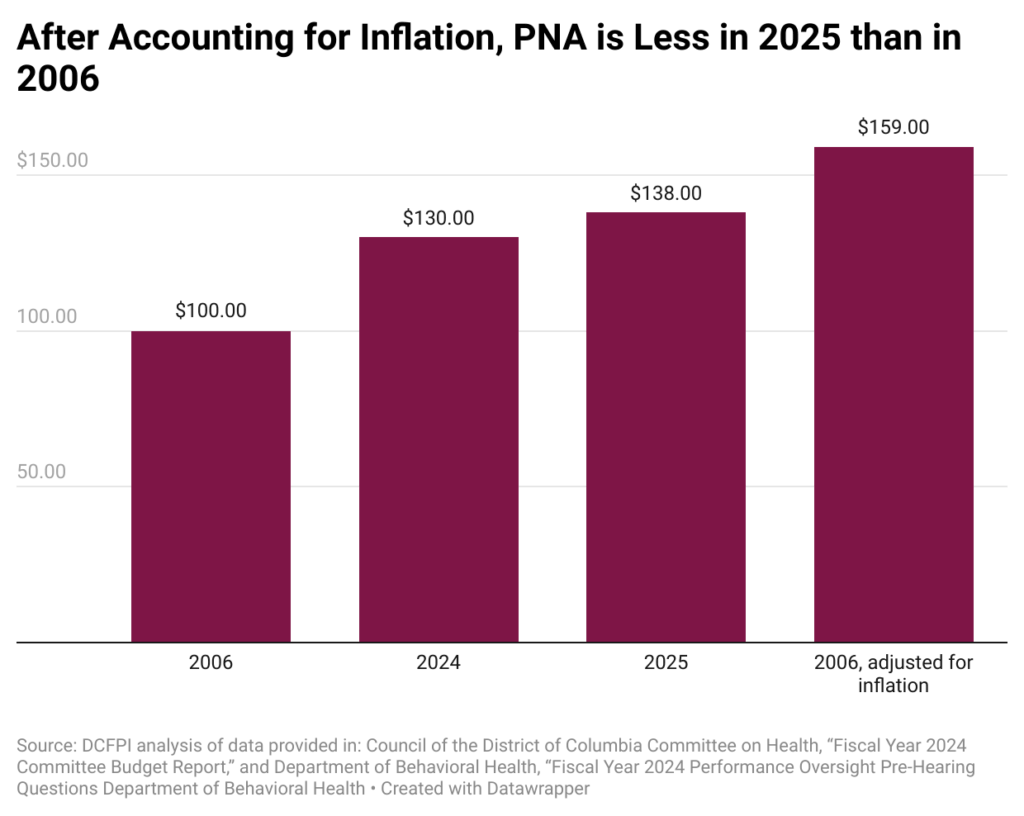

From the time DC Council established the PNA at $100 in 2006, it has been inadequate.[14],[15] The District did not implement an annual COLA until January 2023.[16] Recognizing the PNA was inadequate, DC Council increased the PNA to $130 in FY 2024.[17] With the annual COLA adjustment, the PNA is $138 in FY 2025. If the 2006 PNA was adjusted for inflation, it would be $159. In other words, the PNA today is 15 percent less than it was in 2006. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The low PNA in an area with such a high cost of living forces people to choose which personal needs they will forgo.[18] DC Council’s Committee on Health finds the “low PNA can significantly impact the financial stability and well-being of[…]recipients, making it difficult for them to afford necessities and potentially leading to negative health outcomes.”[19] People may not be able to afford copays or over-the-counter medications, for example. The low PNA can also affect their ability to stay connected to family and friends because they cannot afford cell phones, greeting cards, postage, and travel expenses, national research shows.[20] Research has found that family and friend connections lead to better health outcomes and longer lives.[21]

Inadequate PNA Disproportionately Harms Black Residents

While the low PNA affects all District residents who access assisted living through Medicaid, it will disproportionately harm Black residents. Nearly 77 percent of DC residents who are covered by Medicaid are Black, and 76 percent of individuals experiencing homelessness in the District are Black, even though Black residents make up only 41 percent of the District’s population.[22] [23], [24], [25] This is the result of generations of policies and practices that created longstanding racial inequities in housing and wealth, employment and income, education, and health care, which have also shaped the extremely racially disparate composition of the District’s Medicaid participants and its unhoused population.

For example, DC’s Black Codes, laws originating in 1808 that barred Black people from federal employment, and other pervasive labor market discrimination of the past, have combined to lock in a greater likelihood of poverty and hardship and kept Black residents and other non-Black residents of color from living to their fullest.[26] Government-sanctioned practices, such as racist zoning policies, residential segregation, redlining, restrictive covenants, and other practices, widened the racial wealth gap created at the outset by African enslavement. These intentional efforts to oppress Black people have left Black and brown residents of the District less likely to own a home and more likely to rent in a market with extreme and rising costs, with fewer resources to keep from falling behind on rent and facing eviction, and with fewer protections against the risk factors contributing to homelessness.[27]

District Lawmakers Should Increase the PNA to $300

Grounded in the framework that interventions that explicitly address racism will be most successful when informed by Black residents with lived experience, this brief’s recommendation for a more adequate PNA level reflects direct input from six individuals who are over 60 years of age and who have experienced homelessness; an individual who turned down Abrams Hall; the sister of an individual who turned down Abrams Hall; and a case manager of another individual who rejected Abrams Hall. All but one of the seniors interviewed are Black.

Individuals who had experienced homelessness reported in phone interviews that they require between $200 and $600 to cover needs not covered by the facility. They report average monthly costs of:

- $71 for cell phone bills[28]

- $37.50 for medication copays

- $30 for vitamins

- $43 for clothing

- $45 for toiletries

These costs total nearly $227, but respondents flagged that this didn’t include all possible expenses, such as transportation, haircuts, and greeting cards. Respondents also reported that they needed to set aside funds for emergencies.

The interviewee who rejected Abrams Hall started the interview by saying, “[The facility] wanted to take all of my money.” The sister of an individual who turned down Abrams Hall used nearly identical language to describe what led her brother to reject the offer. DCFPI confirmed through interviews that some individuals who rejected Abrams Hall ended up moving in with family or friends or out of the area. DCFPI was not able to identify where others ended up.

More than half of all respondents reported that $300 should be sufficient, with the others reporting figures below and above that amount necessary for them to make ends meet. By increasing the PNA to at least $300, which translates into an annual increase of $1,944, and continuing the annual COLA adjustments, District leaders can ensure residents experiencing homelessness, who are primarily Black, can live with economic security and access the housing and services that meet their needs. The District can also make the most of its investment in Abrams Hall and make progress on ending chronic homelessness. DC leaders should make this happen in the FY 2026 supplemental budget if revenues do not increase sufficiently for it to happen automatically. If potential residents still reject Abrams Hall, leaders should interrogate why and consider further increasing the PNA further or other strategies to boost their participation.

Appendix 1:

For this report, DCFPI conducted phone interviews in the spring of 2025. Interviews, as a method, “collect a richer source of information” to better investigate behavior, opinions, and experiences.[29] These interviews were intended to gain firsthand accounts from individuals over 60 years old about their monthly expenses and what they consider an adequate PNA. We spoke with:

- One individual who turned down Abrams Hall;

- The sister of an individual who turned down Abrams Hall;

- Seven individuals who have experienced homelessness and are over 60 years of age; and,

- The former case manager of an individual who turned down Abrams Hall.

Interviewees received a $50 gift card for their participation. Unfortunately, DCFPI was not able to reach current residents at Abrams Hall, as originally intended.

PNA Interview Questions for Individual Who Rejected Abrams Hall

When and why did you apply for assisted living at Abrams Hall?

What led you to decline Abrams Hall? What were your other housing options?

- Did these options lead you to decline the offer from Abrams Hall?

- Did you experience any challenges with the application process?

Have you heard of the personal needs allowance?

- If so, can you describe what the PNA is?

- <<that’s correct, or that’s okay, I can explain it>> The allowance means that residents in Abrams Hall can only keep $75 to $100 of their monthly income while in assisted living.

When did you learn about the PNA or income limit?

Prompt if needed: Did you learn about this before or after you applied for assisted living?

Did the PNA/income limit affect your decision to turn down Abrams Hall? (if they give a short answer, ask them to elaborate).

How did your case manager respond to your decision? What do you think is a PNA that would cover the costs?

How much of your own income do you spend monthly on:

- A cell phone?

- Medication copays?

- Doctor copays?

- Vitamins?

- Clothing?

- Toiletries?

Demographic questions:

- How old are you?

- What is your gender?

- What is your race?

- Are you Hispanic/Latino/Latina?

- Were you born in DC? If not, how long have you lived here?

Is there anything else you’d like to share about your experience that we haven’t covered yet?

PNA Interview Questions for Individuals Who Are Over 60 Years Old and Have Experienced Homelessness

Have you heard that the District funded an assisted living program for people experiencing homelessness, called Abrams Hall?

At Abrams Hall, residents keep $130 of their income for expenses not provided by the program as a personal needs allowance (PNA). The program provides meals, housekeeping, and laundry service.

What do you think is a PNA/income limit that would cover these costs?

How much of your own income do you spend monthly on:

- A cell phone?

- Medication copays?

- Doctor copays?

- Vitamins?

- Clothing?

- Toiletries?

Demographic questions:

- How old are you?

- What is your gender?

- What is your race?

- Are you Hispanic/Latino/Latina?

- Were you born in DC? If not, how long have you lived here?

- Melissa Byrd, Senior Deputy Director and Medicaid Director, “2023 Retroactive Payment of State Supplement and January 2025 Payment Levels.” Addressed to Adult Foster Care Home Operators. Transmittal #25-01. January 27, 2025.

- Email correspondence with Mia Norwood, Case Manager Supervisor, PSH at Housing Up, May 14, 2025; and interview with case manager for a client who rejected assisted living because of the PNA.

- Congress is currently considering significant changes to Medicaid. At this time, none of the publicized changes affect coverage of assisted living.

- DCFPI analysis of data provided in: Council of the District of Columbia Committee on Health, “Fiscal Year 2024 Committee Budget Report,” April 26, 2023; and Department of Behavioral Health, “Fiscal Year 2024 Performance Oversight Pre-Hearing Questions Department of Behavioral Health;” Accessed June 27, 2025.

- DCFPI analysis of data in Business Wire, “Long-Term Care Costs Increase in Washington DC, Exceeding National Costs, March 4, 2025.DCFPI analysis of data found at Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the US Department of Health and Human Services, “Poverty Guidelines,” Viewed June 16, 2025.

- National Institute for Medical Respite Care, “Barriers to Accessing Higher Levels of Care: Implications for Medical Respite Care Programs,” February 2022.

- National Institute for Medical Respite Care, “Barriers to Accessing Higher Levels of Care: Implications for Medical Respite Care Programs,” February 2022.

- Email correspondence with Mia Norwood, Case Manager Supervisor, PSH at Housing Up, May 14, 2025.

- Email correspondence with Mia Norwood, Case Manager Supervisor, PSH at Housing Up, May 14, 2025.

- Reported to author by Housing Up staff, May 2025.

- DC Department of Human Services, “Permanent Supportive Housing for Individuals and Families (Project Based, Tenant Based, Local Veterans,” Accessed May 9, 2025.

- Social Security Administration, “Supplemental Security Income (SSI) Overview,” Accessed May 19, 2025.

- Social Security Administration, “How much you could get from SSI,” Accessed May 19, 2025.

- The District set PNAs for nursing homes and community residence facilities in 1998. Department of Health, “Notice of Final Rulemaking on Title 29 Chapter 14,” published at 35 DCR 964, February 12, 1988.

- Department of Health, “Notice of Final Rulemaking on Title 29 Chapter 14,” Published in 53 DCR 466, October 20, 2006.

- DC Department of Health Care Finance, “Transmittal 23-13 Personal Needs Allowance Increase,” January 31, 2023.

- Council of the District of Columbia, Committee of the Whole Committee Report on Bill 25-203, the “Fiscal Year 2024 Local Budget Act of 2023,” May 16, 2023.

- Council of the District of Columbia Committee on Health, “Fiscal Year 2024 Committee Budget Report,” April 26, 2023.

- Council of the District of Columbia Committee on Health, “Fiscal Year 2024 Committee Budget Report,” April 26, 2023, page 55.

- Hector Ortiz, “Personal Needs Allowances for Residents Long Term Care Facilities: A State by State Analysis,” The National Long-Term Care Ombudsman Resource Center,” March 31, 2009.

- Usar Suragar and Debra Hain, “Approaches to enhance social connection in older adults: an integrative review of literature,” Aging and Health Research, Volume 1, Issue 3, September 2021.

- KFF, “State Health Facts: Distribution of People Ages 0-64 with Medicaid by Race/Ethnicity,” 2023.

- Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments, “Homelessness in Metropolitan Washington: Results and Analysis from the Annua(PIT) Count of Persons Experiencing Homelessness,” May 15, 2024.

- Ibid.

- United States Census Bureau, 2023 American Community Survey, Accessed on June 16, 2025.

- Doni Crawford and Kamolika Das, “Black Workers Matter,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute. January 28, 2020.

- Black Homeownership Strikeforce, “District of Columbia Black Homeownership Strike Force Final Report: Recommendations for increasing Black homeownership in the District,” October 2022.

- One individual was only able to provide his total cell phone cost which includes his daughter’s phone. DCFPI cut this expense in half to reflect his portion of the bill.

- Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Libraries, “Research Methods Guide: Interview Research,” Updated August 21, 2023.