Chairperson McDuffie and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Erica Williams, executive director of the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. DCFPI is a nonprofit organization that shapes racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future.

Despite calling it a “growth agenda,” Mayor Bowser’s budget slashes and eliminates programs that help families make ends meet and improve the life trajectories of children, exacerbating racial inequity and keeping families from staying economically active during a local downturn. Her fiscal year (FY) 2026 budget, like last year’s proposal, demands the biggest sacrifices from DC’s lowest income residents, which would set back the progress that DC has made on poverty reduction and greater economic inclusion. None of this is good for growth or creating a strong, equitable economy.

My testimony focuses on the mayor’s harmful move to eliminate DC’s new local Child Tax Credit (CTC) and baby bonds program, as well as policies to raise critically needed revenue, minimize cuts to basic human needs programs, and avoid balancing the budget on the backs of DC’s Black and brown residents struggling on low incomes.

DC Council Should Restore the DC Child Tax Credit

A history of racist policy and practice and its ongoing effects has resulted in tens of thousands of Black and brown children in DC growing up in families experiencing economic hardship. The committee and DC Council should reject the mayor’s proposal to eliminate DC’s local version of the CTC, a critical tool for reducing child poverty and improving child outcomes.

Child poverty is higher in DC than nationally and disparities between the well-being of Black children and white children are extreme. While nearly 1 in 3 Black children in DC lives in a family with income below the poverty line (about $32,000 for a single parent family of four), virtually no white children do.[1] In fact, over 99 percent of white children live above the poverty line. Child poverty is also closely linked to place in DC and is heavily concentrated East of the River, which has suffered from systemic racism and economic divestment for decades. Wards 7 and 8 are predominately Black and had child poverty rates over 30 percent, on average, between 2019 and 2023.[2]

Child Poverty is Anti-Growth

Poverty and economic hardship have deep, long-lasting effects on children, especially if it begins in their early years and persists over a long period of their childhood.[3] Parents with low incomes may struggle to provide nutritious meals or enriching learning environments in the home, or they may lack the means to access high quality child care. Parents with little income also carry enormous stress of how to pay the rent, buy food and other necessities, and for some, of living in less healthy or safe neighborhoods.

Nationally, nearly 40 percent of children experience at least one year of poverty before they turn 18, with nearly 11 percent experiencing persistent poverty, according to longitudinal research by the Urban Institute.[4] Stark differences by race mean that 3 out of 4 Black children experience at least one year of poverty, more than half of them persistently, compared with 3 in 10 white children and far fewer (4 percent) persistently. The same study finds that children who live in poverty for longer do less well than those who live in poverty for just one year. They are less likely to graduate from high school, attend college, or complete college; less likely to have consistent employment as adults; and more likely to have teen births. That Black children are more likely to be poor and persistently poor than children overall, and white children in particular, means that Black people experience wider spread intergenerational barriers to success. It also suggests that shortening the length of child poverty matters to disrupting cycles of poverty.

Income Changes Life Trajectories

Getting cash to families that have poverty-level and low incomes can make a long-lasting difference in children’s lives and how they fare as adults. For example, a longitudinal study of federal Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) increases on child outcomes found that a $1,000 increase in family income from the credit raised math and reading test scores for children and resulted in higher earnings in their adulthood.[5] Another study showed that for families with young children with incomes below $25,000, an income boost of just $3,000 would result in a 17 percent increase in adult earnings for those children.[6] Boosts to income also can make it likelier that older children access higher education by making college or the costs of attendance more affordable.[7] And, boosts to cash income may improve health by way of increased educational attainment.[8] Increased income for families living in poverty also has been shown to improve health more directly as well through healthier behaviors, access to healthier foods, and reduced stress.[9]

Poverty Reduction Boosts the Economy

Increasing incomes to reduce poverty also benefits the economy more broadly. One study looking at disparities in innovation—an important economic driver—by race, gender, and income, finds that if children in the bottom 80 percent of the income distribution in DC were to grow up to invent at the same rate as children from the top 20 percent, the District would have five times as many children growing up to be inventors.[10] In other words, if income inequality were eliminated, we’d have more people driving the future of our economy and, moreover, these people would come from more diverse backgrounds that bring new perspective to new innovations. Another study found that even in the short-run, economic supports can help people with entrepreneurial ideas take risks and pursue those ideas.[11] Another study estimates that the costs of child poverty to the national economy at over $1 trillion per year, or 5.4 percent of gross domestic product because it depresses economic productivity and increases costs of crime, health care, child homelessness, and child welfare.[12]

This all means the economy could be strengthened substantially if policies greatly reduced or eliminated poverty, and this would be true at the local level as well. If the District truly wants to pursue equitable economic growth, then further investing in the local CTC, not eliminating it, is the right way to move forward.

DC Council Should Restore Funding for and Quickly Implement the Baby Bonds Program

In 2021 and 2022, Chairman McDuffie laudably championed the “Child Wealth Building Act of 2021,” which established a DC baby bonds program to reduce the substantial racial wealth gap in the District. As the result of a long and well-documented history of deliberately racist policies, exploitative and extractive systems, and white racial violence against Black residents, the District has one of the largest racial wealth gaps in the country. In the DC area, white households have 81 times the wealth of Black households.[13] Despite this fact, the program has been at risk since its adoption, and for the second time since its adoption, the mayor’s budget has proposed its all-out elimination in FY 2026. The committee and DC Council should restore its funding and promise.

The racial wealth gap causes intergenerational harm that holds back families, communities, and the local economy. Wealthy families can pay for an elite education for their children, start a business, buy a home in a safe and amenity-rich neighborhood, weather a job loss or illness, and provide their children and grandchildren an inheritance to build on.[14] Families with little or no wealth are denied these opportunities as well as the freedom and security wealth provides. In the words of baby bonds scholar and advocate Darrick Hamilton, “the reality is that wealth is the paramount indicator of economic prosperity and well-being…[W]hen it comes to economic security, wealth is both the beginning and the end.”[15] That Black residents of the District—the single largest racial group in DC—lack wealth, is bad for DC’s economy, as a robust body of research shows that inequality weakens and destabilizes economic growth, especially growth that is equitably shared.

To ensure the baby bonds program achieves its long-term goals, DC officials must get the program up and running. The Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO) issued a Notice of Proposed Regulations for the program in December 2022 but as of February 2025 had not issued its final rules.[16] The OCFO had to pause the administrative build-out of the program due to data constraints. Under current law, the Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) cannot disclose a child’s Medicaid status to the OCFO because it violates the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).[17] Without these data, the OCFO does not know how many children are eligible and doesn’t know their names. The proposed rules would require the Department of Human Services (DHS) to verify eligibility and enroll the children into the program. To date, DHS has not enrolled any children in the program.

After restoring funds for baby bonds, CBED should work with the Committee on Health and Committee on Human Services to authorize data sharing of Medicaid data (while adhering to HIPAA rules) and statutorily mandate coordination across the three agencies to facilitate implementation of the baby bonds program. Together, the committees should also provide guidance on which DC agencies are responsible for conducting targeted public outreach and responding to families’ inquiries. DC agencies have published limited information about the program, meaning that parents of eligible children may not know that their children qualify for the program or understand what steps they need to take to ensure their children are enrolled. Outreach could include a public media campaign, a launch event, regular and widely-publicized program updates, and an online program dashboard tracking eligibility, enrollment, and other key data points. Greater outreach is warranted in Wards 5, 7, and 8, where children who are likelier to be eligible live.

DC Council Should Raise Taxes on High Income Residents, Eliminate Tax Preferences that Protect and Further Concentrate Wealth, and Lay the Foundation for a Business Activity Tax

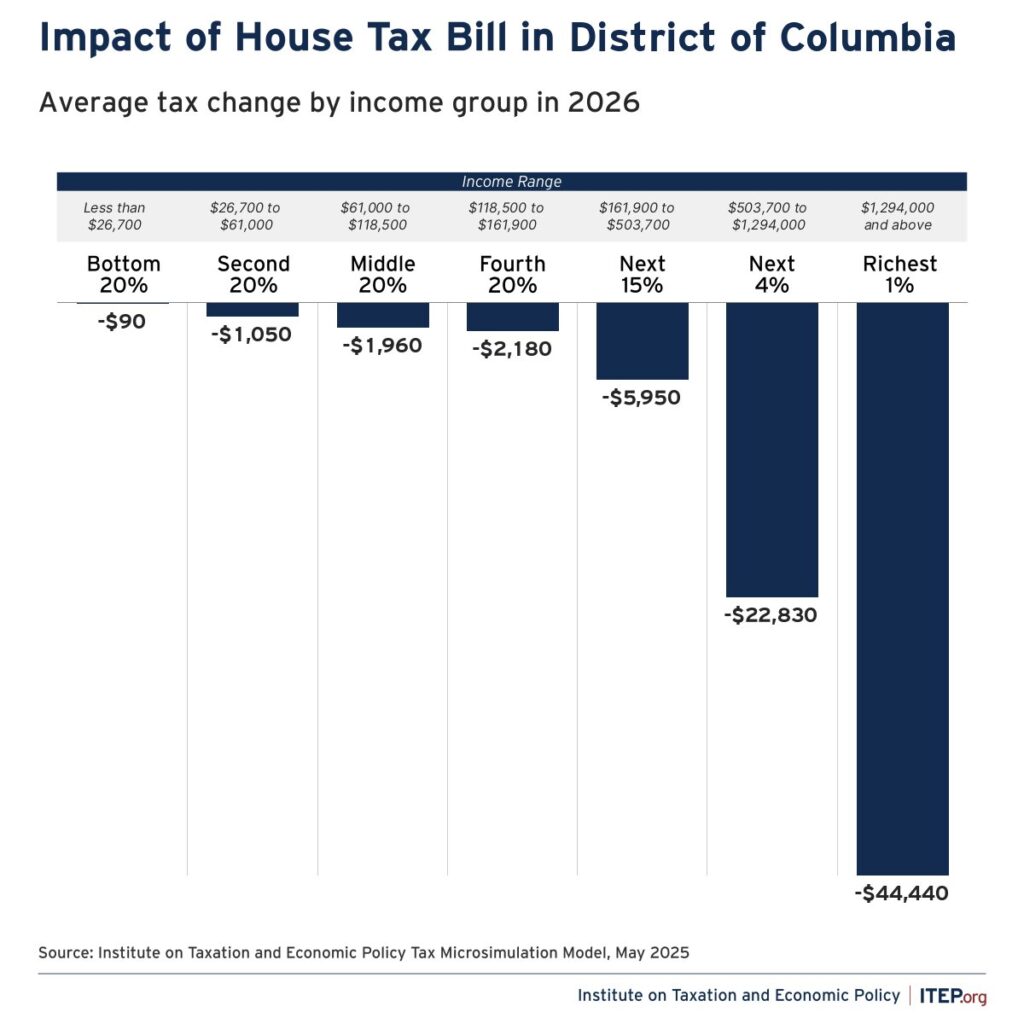

To ensure that this budget is not balanced on the backs of Black, brown, and immigrant residents with low incomes, the Council will not only need to reprioritize allocation of revenues, but also raise new revenues. DCFPI has written recently about how a balanced approach that includes revenue to minimize cuts is the prudent approach to mitigating the downturn that DC is entering due to federal layoffs.[18] Lessons from past recessions show that greater public investment in economic security programs during economic downturns aids in achieving a quicker, more robust recovery. And, even as the District cannot replicate the level of investment of federal aid packages approved in recent recessions, it can still minimize harm by avoiding an overreliance on cuts and destabilizing families and communities unnecessarily. DC has a range of options for raising revenue to help weather the storm of federal layoffs and threats to federal funding of basic human needs like health coverage and food assistance that make way for massive tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans. The tax cuts being advanced in Congress would deliver an average annual cut of $47,000 to the top 1 percent of DC households and $23,000 to the next 4 percent of households (Figure 1). This offers the District the perfect opportunity to recoup the loss of federal dollars for programs through higher taxes on the top 5 percent of households whose incomes are over $500,000 annually (for the top 1 percent, household income exceeds about $1.3 million). Furthermore, DC would not be alone in taking a balanced approach. Maryland just passed a revenue raising package that increases taxes on high incomes and capital gains, limits itemized deductions, and strengthens its state child tax credit in order to minimize harm in the face of the current federal storm.[19]

Here are several options for raising revenue targeted at the top 5 percent of DC households:

Raise Taxes on the Highest Incomes

DC can ask for more from the richest households, which are predominantly white, by increasing marginal rates on top earners and adding at least one new income bracket for incomes above $3 million. For example, the following rate structure would raise $109 million annually:

- For incomes between $500,000 – $1 million, increase the rate by .25 percent, to 10 percent;

- For incomes between $1 – $3 million, increase the rate by .75 percent, to at least 11.5 percent; and,

- For incomes above $3 million, increase the rate by 1.75 percent, to at least 12.5 percent.[20]

DC can also increase the phaseout rate on itemized deductions from 5 percent to 7.5 percent, as proposed by the DC Tax Revision Commission (TRC). This would raise an estimated $26 million and reduce income and racial inequality.[21] DC Council could adopt this proposal or go further and increase the phaseout rate to 10 percent, raising $52 million to restore funding for critical programs.

Raise Taxes on Capital Gains

The federal and DC governments tax income from wealth more favorably than income from work, particularly capital gains income, which benefits very wealthy, white households the most.[22] This advantage contributes to the reality that DC’s tax code still favors the top 5 percent, and in DC, 0.4 percent of households, or roughly 1,500 households, have net worth over $30 million, and together hold half of all the wealth in DC, to the tune of $183 billion. A sizeable share of this is held in unrealized capital gains.[23]

DC should consider adding a surcharge on realized capital gains targeted at the top 5 percent of households in the income distribution. We propose a rate increase of 1 percentage point for taxpayers with an adjusted gross income (AGI) over $500,000 and for capital gains income at or above that level only, meaning capital gains below the threshold would still benefit from the lower marginal tax rates in current law. The proposal would raise the income tax on capital gains income by two percentage points for taxpayers with an AGI between $750,000 and $1 million and by 3 percentage points for taxpayers with an AGI over $1 million. The proposal would raise $123 million annually, affecting just 1.85 percent of taxpayers overall, and all of them in the top 5 percent of the income distribution.[24]

Further Increase the Progressivity of DC’s Property Tax

DC can expand on last year’s step toward a more progressive property tax by adding more marginal rates for single family homes with taxable value at the 95th percentile of home values or higher (in 2023, this threshold was $1.5 million but would likely be higher today). DCFPI has proposed indexing the tax to the 95th percentile of home values in perpetuity and excluding homeowners receiving exemptions or credits for low income or for seniors, veterans, or people living with a disability.[25]

Lay the Groundwork for Potential Future Implementation of a Business Activity Tax

Building on the research of the DC Tax Revision Commission (TRC), DCFPI co-authored with former TRC Director Nick Johnson a fleshed-out proposal for a Business Activity Tax (BAT), which would expand DC’s tax base and make business taxes fairer by closing a federal loophole benefiting non-resident owners of pass-through businesses.[26] DCFPI estimates that a 2 percent rate could yield $505 million annually in new revenue and that this revenue could be used to reverse in full the payroll tax increase on businesses that was adopted in FY 2025. This would mean a net tax cut of about $257 million for DC’s home-grown businesses that already make meaningful tax contributions to DC’s shared resources. DC can lay the groundwork for a BAT by firming up its estimate of how much the BAT would raise, developing a better understanding of the rulemaking and implementation steps needed, and other details, through a pro-forma, or hypothetical return, that helps the OCFO assess liability.

- DCFPI analysis of US Census Bureau American Community Survey data, 2019-2023 5-year public use microdata set.

- Connor Zielinski, “DC Contends with Extreme Child Poverty Disparities by Race, Place, and Age,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, March 10, 2025.

- For a thorough review of the literature, see: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “Chapter 3: Consequences of Child Poverty.” A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019.

- Caroline Ratcliffe, “Child Poverty and Adult Success,” Urban Institute, 2015.

- Gordon Dahl and Lance Lochner, “Correction and Addendum to ‘The Impact of Family Income on Child Achievement: Evidence from the Earned Income Tax Credit,” March 1, 2016.

- Greg J. Duncan and Katherine Magnuson, “The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty,” Pathways, Winter 2011.

- Dayanand S. Manoli and Nicholas Turner, “Cash-on-hand and College Enrollment: Evidence From Population Tax Data and Policy Nonlinearities,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 19836, revised April 2016.

- For a thorough review of the literature on the health benefits of income support, see Arloc Sherman, Samantha Waxman, and Kris Cox, “Income Support Associated With Improved Health Outcomes for Children, Many Studies Show,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2021.

- Hilary W. Hoynes, Douglas L. Miller, and David Simon, “The EITC: Linking Income to Real Health Outcomes,” University of California Davis Center for Poverty Research, Policy Brief, 2013 and Kelli A. Komro et al., “Effects of State-Level Earned Income Tax Credit Laws on Birth Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity,” Health Equity, March 13, 2019.

- Wesley Tharpe, Michael Leachman, and Matt Saenz., “Tapping More People’s Capacity to Innovate Can Help States Thrive,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, December 9, 2020.

- Gareth Olds, “Food Stamp Entrepreneurs.,” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 16-143, June 2016. This study finds that one of the things that holds back entrepreneurship is the risk of leaving wage employment to pursue ideas, and having income supports (or economic supports that mimic income like food assistance) help lessen that risk.

- See summary starting on page 89 in National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “Chapter 3: Consequences of Child Poverty.” A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019; McLaughlin, M., and Rank, M.R., “Estimating the economic cost of childhood poverty in the United States,” Social Work Research, 42(2), 73–83, 2018.

- Kilolo Kijakazi, Rachel Marie Brooks Atkins, Mark Paul, Anne Price, Darrick Hamilton, and William A. Darity Jr., “The Color of Wealth in the Nation’s Capital,” the Urban Institute, Duke University, The New School, and the Insight Center for Community Economic Development, November 2016.

- Darrick Hamilton, Emanuel Nieves, Shira Markoff, and David Newville, “A Birthright to Capital: Equitably Designing Baby Bonds to Promote Economic and Racial Justice,” Prosperity Now and the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at The Ohio State University, February 2020.

- Ibid, page 1.

- Office of the Chief Financial Officer, “Notice of Proposed Rulemaking – 9 DCMR Ch. 43 – District of Columbia Child Trust Fund,” District of Columbia Register (Volume 69, Number 51), December 23, 2022; email communication with Office of the Chief Financial Officer, February 2025.

- Conversation with Office of Chief Financial Officer, 2025.

- Erica Williams, “Raising Revenue Is An Urgent and Practical Approach to Reducing the Harm of DC’s Recession,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, May 21, 2025.

- Miles Trinidad, “Maryland’s New Budget Boosts Tax Revenue and Equity,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, May 6, 2025.

- Unpublished analysis for DCFPI by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

- “Limit Itemized Deductions,” DC Tax Revision Commission.

- Tazra Mitchell, “Taxing Capital Gains More Robustly Can Help Reduce DC’s Racial Wealth Gap,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 31, 2023.

- Carl Davis, Emma Sifre, and Spandan Marasini, “The Geographic Distribution of Extreme Wealth in the U.S.: Estimating Wealth Levels and Potential Wealth Tax Bases Across States,” Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP), October 2022. And, data provided by ITEP to DCFPI in October 2022. Data reflects ITEP’s Microsimulation Tax Model analysis, using data from the Internal Revenue Services, Survey of Consumer Finances, Forbes, and other sources. Ultra wealthy includes those with wealth of at least $30 million.

- Unpublished analysis for DCFPI by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

- Eliana Golding, “DC Can Advance Racial Equity and Black Homeownership through the Property Tax,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, October 17, 2023.

- Nick Johnson, Tazra Mitchell, and Erica Williams, “A Business Activity Tax Would Make DC’s Tax System More Equitable While Raising Revenue,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 30, 2025.