Overall and Black child poverty rates returned to extreme highs in 2024 after lawmakers failed to sustain pandemic expansions of local and federal economic supports. DC’s Black child poverty rate—which drives the overall child poverty rate—increased significantly from 2023 to 2024, but was statistically unchanged compared to the extremely high rates of 2013 to 2018.

A history of racist policy and practice and its ongoing effects has resulted in tens of thousands of Black and brown children growing up in families experiencing economic hardship in DC. Some of the factors driving this chronic hardship include longstanding barriers to employment, inadequate work hours, and good pay for Black workers and families. The District’s high cost of living compounds this issue, making it extremely difficult for families experiencing poverty to afford the essentials. At the same time, families now face what is likely the biggest reduction to DC’s safety net in a generation after massive cuts—proposed by Mayor Bowser and adopted by DC Council—in the fiscal year (FY) 2026 budget and over the four-year financial plan. DC policymakers must commit to ending child poverty and deeply invest in programs aimed at reducing racial disparities and economic hardship.

Child Poverty Disproportionately Impacts Black Children

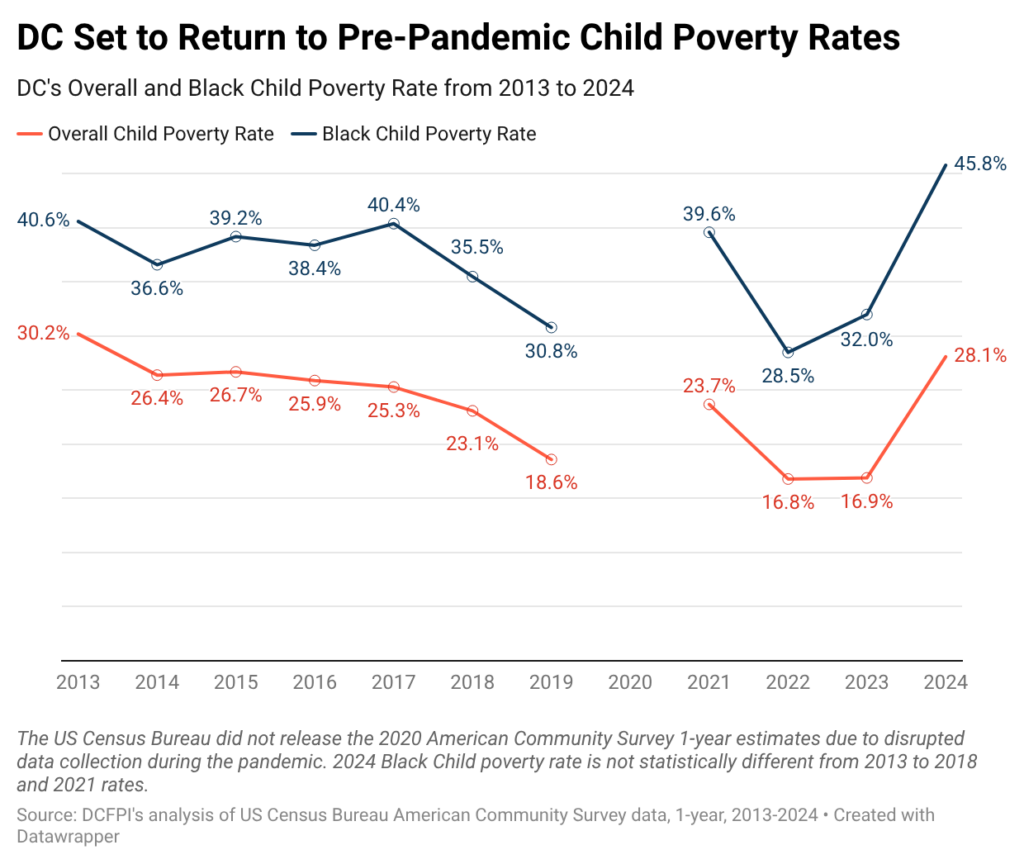

DC’s child poverty rate spiked by 11.2 percentage points from 2023 to 2024 to reach 28.1 percent, the largest year-to-year increase in the past decade. DC has had extremely high child poverty rates before. Looking at the decade prior, the poverty rate was above 23 percent and statistically unchanged from 2013 to 2018, meaning variations in the rates in those years may not be meaningful (Figure 1). The District saw a sizable and statistically significant decrease in child poverty in 2022, and sustained in 2023. This is likely due to direct cash supports, such as unemployment compensation and excluded worker disbursements, as well as other policies that helped keep people afloat until they were able to get back to work, including a moratorium on evictions and expanded food assistance. The return to extremely high child poverty in 2024 appears to come on the heels of the loss of pandemic-era public investments in economic security.

Figure 1

Black child poverty drove DC’s high child poverty rate over the last decade and has been around 10 to 18 percentage points higher than the overall child poverty rate from 2013 to 2024. The increase in the overall child poverty rate in 2024 resulted from an even larger, statistically significant increase in the Black child poverty rate to 45.8 percent in 2024.

Systemic Racism is Behind High Poverty Rate for Black Children

Decades of segregation and housing, labor market, and educational discrimination have resulted in stark racial inequities that limit economic opportunities for Black workers, which in turn hold down family income and exacerbate Black child poverty. One key factor in DC is that—due to historic and systemic racism—employment is less secure for Black workers than white workers. In 2024, 10 percent of Black workers in DC were unemployed compared to 2 percent of white workers. In fact, Black unemployment has not fallen below 8 percent since 2001. Likewise, in 2024, nearly 15 percent of Black workers were underemployed, meaning they couldn’t attain full time work matching their skillsets, compared with under 5 percent of white workers, and this disparity has also been chronic. Unemployment makes families three times more likely to be poor, according to research by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and among working families underemployment increases the likelihood of living in poverty as well.

The challenges for Black households living in poverty are compounded by DC’s high cost of living, especially for families with children. Black families dedicate an estimated 32 percent of their annual income to support one child with child care, forcing them to make impossible choices every day between child care, housing, and food.

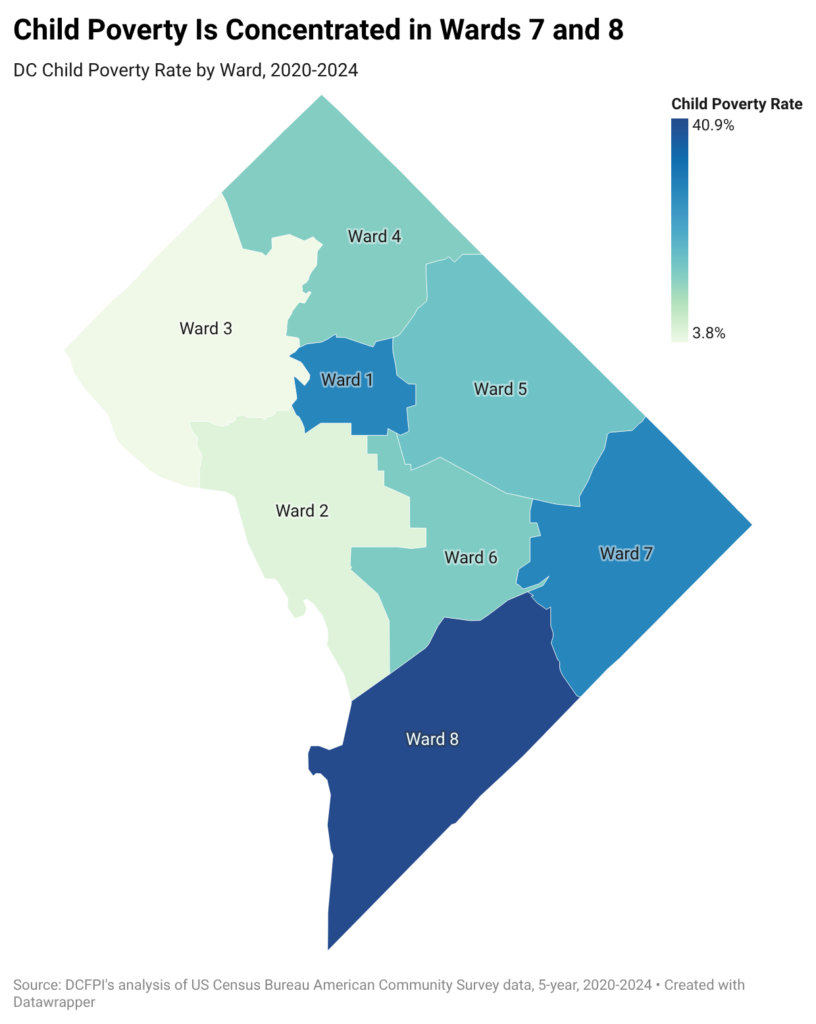

Racial disparities in the child poverty rate are also evident across DC neighborhoods. Using five-year pooled Census data, on average from 2020-2024, nearly 41 percent of children in Ward 8, which is predominantly Black, lived below the poverty line, compared to 3.8 percent of children in Ward 3, which is predominantly white (Figure 2).

Figure 2

This disparity reflects many decades of systemic disinvestment, discrimination, racism, and isolation experienced by residents living East of the River. This history and its ongoing effects has resulted in unequal outcomes across a range of indicators of well-being and unequal access for the essentials, from grocery store access to transportation availability. The data on both the racial and geographic breakdown of child poverty in DC make clear that any discussion of child poverty in the District must center the needs of Black children and their families.

DC Lawmakers Need to Commit to Deep Investments Across the Board to Reduce Black Child Poverty

DC Council recently passed legislation that would meaningfully address child poverty, including expanding DC’s Earned Income Tax Credit and enacting a CTC, which will reduce poverty across the board by an estimated 20 percent (However, these may not be implemented, because Congress overturned the legislation ensuring funding for these initiatives.) Yet many of these same lawmakers were willing to sacrifice key poverty fighting programs and benefits in fiscal year 2026, balancing the budget on the backs of low income, predominantly Black residents. These cuts come alongside the historic cuts to the federal safety net outlined in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act enacted in 2025.

For example, without any changes to the financial plan, 7,000 families will have their TANF benefits significantly reduced in FY 2027, harming very low-income families with children. The mayor and Council also severely underfunded the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), which helps families facing eviction. Expanding one set of initiatives to address poverty while cutting others is counterproductive.

DC lawmakers have an expansive toolkit of evidence-based policies to combat child poverty, yet they have made decisions that destabilize families already struggling to get by. The fall in the child poverty rate following the pandemic proves that public investments can meaningfully help families meet their basic needs and set children up for a stronger future. Lawmakers just need to be willing to choose those investments.