Chairperson Henderson and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Kate Coventry, and I am the Director of Legislative Strategy at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI). DCFPI is a non-profit organization that shapes racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future.

My testimony focuses on the harm caused by recent changes to the DC Health Care Alliance program (the Alliance) and the actions that the Council can take to reduce this harm.

More than 2,000 Residents Have Already Lost Alliance Coverage and Have Few Adequate Alternatives

Lawmakers reduced the income threshold for Alliance eligibility in the fiscal year (FY) 2026 budget. For adults over the age of 20, the threshold went from 210 percent of the federal poverty line (FPL), $57,300 for a family of three, in FY 2025 to 138 percent of FPL in FY 2026.[1] Approximately 2,200 individuals lost coverage on October 1st because of this change.[2]

Newly ineligible residents will struggle to pay for health care, may avoid or delay needed care and even die from diseases that could have been successfully treated if the individual received timely care.[3] The Alliance provides health coverage to residents with low incomes who are not eligible for Medicaid—primarily immigrants. This eligibility change comes as the federal government escalates deportations and targets immigrants for other benefits cuts. Congress has recently excluded more lawfully present immigrants from Medicaid, and federal agents are rounding up immigrants, including those with legal statuses.[4], [5]

Alliance Changes Vastly Reduce Its Reach

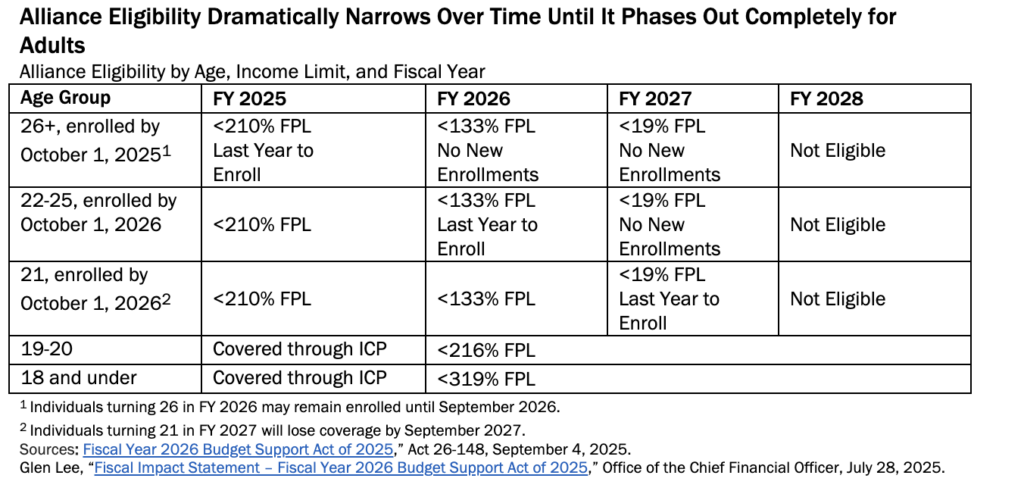

DC lawmakers made several other changes to the Alliance program that will greatly reduce the number of people enrolled.

They shifted the reimbursement model. The Alliance was previously a managed care program and is now a fee-for-service program. Under managed care, the District paid a monthly capitated payment per Alliance enrollee, a set amount of money to cover the predicted monthly costs of covered care for a specific patient.[6] Now the District will pay health care providers for each service performed.[7] DC Health Care Finance leaders report that this shift should yield savings.

They ended the locally-funded Immigrant Children’s Program (ICP) and shifted recipients to the Alliance. ICP provided health coverage to District residents who were 20 years old and younger and didn’t qualify for Medicaid. For children up to age 18, family income had to be at or below 319 percent of the FPL and for 19- and 20-year-olds, at or below 216 percent of the FPL (Table 1).[8] The income thresholds for these age groups did not change under the budget. The DC Council Committee on Health reported that the Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF) assured them that “children’s services will remain essentially the same as those they received through ICP.”[9] But the agency also announced that benefits will be limited to primary care services, inpatient and outpatient acute-care hospital services, emergency medical transportation services, and prescription drugs. Alliance enrollees will no longer have access to specialty care, including home health services, nursing facility services, and services provided by an inpatient psychiatric hospital.

They instituted an enrollment moratorium. Beginning in October 2025, or FY 2026, individuals over the age of 26 were no longer allowed to newly enroll in the program. Enrollment will be further restricted in October 2026, when only individuals under age 21 will be allowed to newly enroll. Existing enrollees have a 90-day grace period to renew their coverage, or they will be dropped from the program. Mayor Bowser initially proposed a moratorium for all individuals over 21, but the Committee on Health found funding to increase eligibility to age 25 for FY 2026 only. Unless lawmakers act, the moratorium on new enrollments will drop to age 21 in FY 2027.

They further reduced the income threshold for eligibility. For adults, the income threshold will decrease from 138 percent of FPL in FY 2026 to 19 percent of FPL in FY 2027 before eliminating the program for adults over the age of 20.

Table 1.

They also made it more difficult for Alliance applicants and recipients to prove residency. Applicants will now have to provide two proofs of residency rather than one, and the legislation limits the types of proofs DC will accept.[10] Previously a DC One Card–the consolidated credential designed to give residents access to DC government facilities and programs–was sufficient to prove residency. But now the District is moving away from the One Cards as a form of identification because the card is valid for five years and there were concerns that former DC residents were using them after moving to another jurisdiction.[11] Those with exceptional circumstances, including people experiencing homelessness or domestic violence, or dealing with a noncustodial parent who refuses to release verification documentation, will not be required to provide two proofs of residency.[12] The Committee on Health added public school enrollment as an allowable single proof of residence.

They ultimately rejected proposed changes that would have made it more difficult for individuals to apply and recertify for the program. The mayor proposed requiring all beneficiaries to recertify in person at a Department of Human Services (DHS) service center every six months, rather than once per year virtually under existing law. The Committee on Health stated, “this policy change will unnecessarily harm Alliance beneficiaries who are District residents and could lead to an outsized number of people falsely losing their health insurance due to factors outside of their control,” and thus rejected this change in their budget.[13] The Committee reports that in the past when DC required in-person recertifications every six months, there were long wait times, with some people lining up hours before the centers open with no guarantee they could be seen that day.[14]

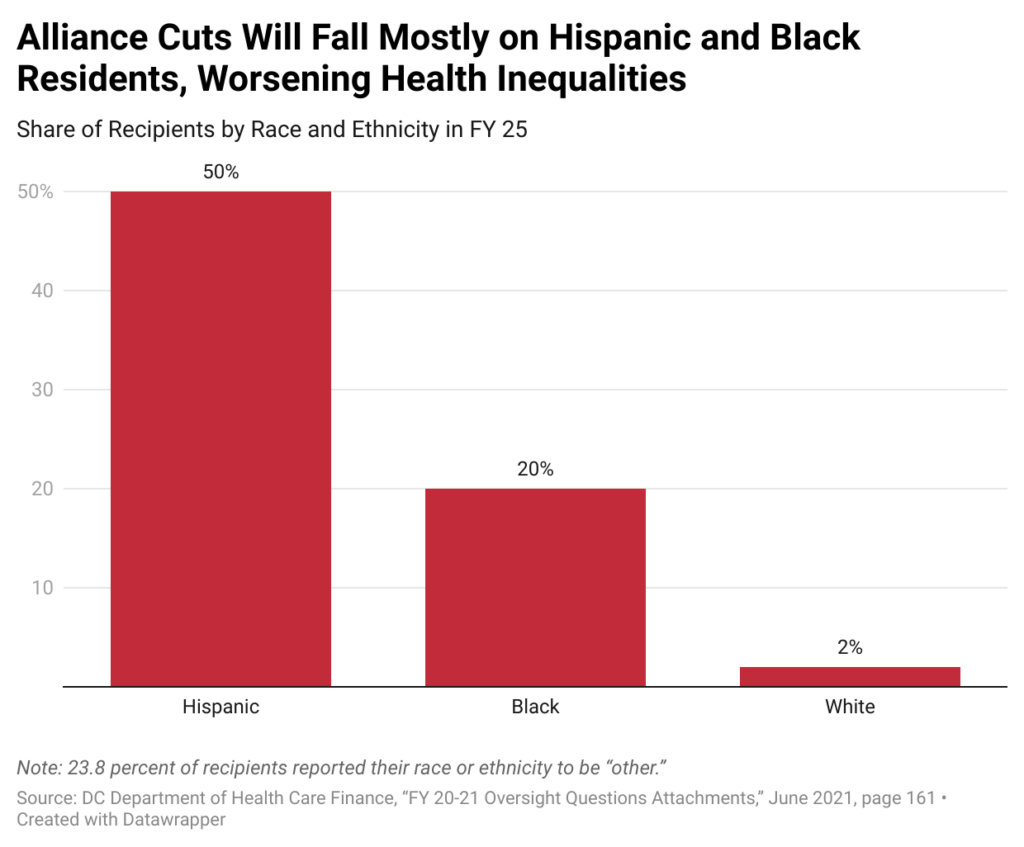

Alliance Cuts Will Primarily Harm Hispanic and Black Residents

Alliance changes will primarily hurt DC’s Hispanic and Black residents, including those who are documented and undocumented.[15] In FY 2020, 50 percent of Alliance recipients were Hispanic, 20 percent were Black, and just over 2 percent of recipients were white (Figure 1).[16]

Figure 1.

The current federal policy shift on immigration and local changes to the Alliance are part of a long, racist history of restrictions on immigrant access to public benefits. Prior to 1965, immigrants to the United States primarily came from Northern and European countries and federal law did not exclude immigrants from public benefit programs.[17] When federal lawmakers created Medicaid in 1965, they required states to cover everyone in all mandatory coverage groups regardless of their citizenship or immigration status.[18] Then the immigration system also changed in 1965, leading to greater numbers of immigrants coming from Asia and Latin America.[19]

Starting in the early 1970s, Congress and some states began restricting immigrants from public benefit programs due to xenophobia and racism. Political leaders and the press promoted disproven stereotypes to justify exclusion. They used similar stereotypes to make it harder for Black Americans to access benefits as well.[20]

The Nixon administration barred undocumented immigrants from Medicaid, but a federal court overturned that policy.[21] In response in 1986, Congress passed a law barring federal reimbursement of Medicaid services to states for undocumented residents, except for life-threatening medical emergencies.[22] As a result of racist stereotypes and a desire to cut spending on programs that benefited people with low incomes, federal lawmakers excluded many documented immigrants and all undocumented immigrants from Medicaid.

Alliance Cuts Will Harm Immigrant Residents Who Are Particularly in Need with Ripple Effects for All of DC

Immigrants, even those with documented status, have limited health coverage options and thus are in particular need of programs like the Alliance. Many have long been excluded from Medicaid coverage, and some are newly prohibited from Medicaid or no longer eligible for coverage on the ACA marketplace due to actions adopted by Congress in 2025.[23] In addition, noncitizen immigrants regardless of status are more likely to be employed in jobs that have lower wages and lack employer-sponsored health insurance.[24] They are also more likely to work in sectors with higher adverse health risks.[25], [26] Taking away this vital safety net will likely make it harder for some immigrants to stay healthy and remain on the job, harming them and DC’s economy. Other ripple effects of the mayor and DC Council slashing of Alliance include:

Additional Pressure on Federally Qualified Health Centers with Fewer Resources

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) are “safety net” providers, including community health centers and programs serving migrants and people experiencing homelessness.[27] Their main purpose is to improve primary care services in underserved urban and rural communities.[28] FQHCs are obligated to serve patients even if they cannot pay, but they are limited in the services they can provide.[29] They don’t provide cancer treatment, dialysis, or durable medical equipment such as wheelchairs, for example.[30]

While they will care for patients regardless of their ability to pay, FQHCs will likely face a critical funding gap due to the increase in uninsured patients following Alliance cuts. The DC Primary Care Association, the membership organization of local health centers, reports that FQHCs are projected to lose $12.4 million annually when the Alliance is eliminated for adults in FY 2028.[31] FQHC directors report that they will not be able to absorb this loss and that they will have to lay off staff. They fear remaining staff will burn out as a result, and the reduced capacity will force patients to rely on expensive emergency room visits that are not designed for helping patients manage diseases like hypertension and diabetes.

Increased Reliance on Costly Emergency Room Visits

Individuals without insurance often skip preventive care and postpone routine care until they have an emergency.[32], [33] By law, emergency rooms must provide patients with life-saving care even if they lack health insurance. But hospitals can charge these patients higher prices than insured patients.[34] Insurance companies negotiate with hospitals for reduced prices for their clients, but the uninsured do not have the same negotiating opportunities and can be charged thousands of dollars more than insurance companies pay. [35], [36]

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid report that unnecessary emergency room visits should be avoided as “they are costly and consume resources that other individuals with more acute needs may need.”[37] DC emergency rooms already have the longest wait times in the country, averaging 5 hours and 29 minutes, and now many former Alliance patients will seek care in the emergency room, making this wait time increase.[38]

Increased Medical Debt for Residents with Low Incomes

Often hospitals bill uninsured patients and use harmful debt collection practices. And, although District law actually requires hospitals to provide uncompensated care for uninsured people with low incomes (at no less than 3 percent of their operating expenses), they are allowed to count bad debt toward that requirement, which they can later write-off.[39] Because of that loophole, private, nonprofit hospitals in the District spent just 0.80 percent of their operating expenses on free or reduced price care in 2021, for example.[40] Additionally, the District does not require hospitals to inform patients of the availability of financial assistance.[41]

Medical debt harms an individual’s ability to obtain a job, housing, and other lines of credit.[42] The American Cancer Society reports that it is “associated with more days of poor physical and mental health, more years of life lost and higher mortality rates for all-cause and leading causes of death.”[43] Medical debt is also the leading cause of bankruptcy, which harms the broader economy. Fear of medical debt may lead some residents to delay or forgo care. National polling has found that 28 percent of respondents delayed or did not receive health care due to cost.[44]

Loss of Coverage for Pregnant People Just Two Months After Delivery

The District will provide pregnancy-related care through the federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which allows states to cover parents regardless of immigration status as part of covering low-income citizen children from conception to birth. CHIP covers prenatal care, labor, and delivery, but only offers two months of postpartum services. This is inadequate because pregnancy-related complications can develop up to a year after childbearing.[45] Nationally, nearly 12 percent of pregnancy-related deaths occur between 43 to 365 days postpartum.[46] For this reason, the Alliance and Medicaid both offer 12 months of postpartum care. However, as eligibility for the Alliance shrinks, people also ineligible for Medicaid will be left with insufficient postpartum services through CHIP.

The Council Should Create an Advisory Council to Identify Savings and Delay Further Cuts

Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services Wayne Turnage has argued that Alliance costs are increasing too fast but for reasons that are not entirely clear to agency leaders.[47] He testified in the summer of 2025 that the budget would have more than doubled since 2011 from an inflation-adjusted $74.3 million to a projected $247 million in 2026, if lawmakers made no changes to the program, and that the per-enrollee annual cost more than doubled from an inflation-adjusted $2,576 in FY 2011 to a projected cost of $6,671 in FY 2026.[48] However, the projection for FY 2026 is far higher than the approved FY 2025 budget for the Alliance and ICP together, which totaled about $150 million.[49] The agency has not made the assumptions behind this increase public.

Increased health care costs are not outside of the norm for the nation. Health care costs typically grow faster than inflation and have sharply increased in the United States over the last several decades.[50] National health expenditures more than doubled from $2.2 trillion in 2000 to $4.9 trillion in 2023 after adjusting for inflation.[51] Matching the national trend, part of the budget growth is due to an increase in the average age of Alliance recipients whose medical needs have become more complex and expensive.[52] According to Deputy Mayor Turnage, enrollment growth is only a small portion of rising costs, with enrollment growing just over 2 percent annually between FY 2011 and FY 2026, with a projection of 37,000 enrollees in FY 2026.[53] This timeframe, however, masks the enrollment drop that occurred when Council restricted access to the program in 2011 through a requirement for eligibility redeterminations, in person, every six months. Enrollment in the Alliance dropped sharply to about 15,000 in the years following and didn’t rise back up to 20,000 enrollees until that restriction was removed in FY 2023. And, with FY 2025 enrollment at closer to 30,000 across the two programs, it is unclear what assumptions support the FY 2026 enrollment number reported in Turnage’s testimony to Council.

Rather than reaching out to stakeholders for ideas of how to contain costs, DC policymakers plan to eliminate the program for adults above age 20 altogether. Instead, the District should form an advisory council of experts, including current Alliance enrollees, to identify potential areas for savings and unpack cost drivers, with the goal of offering recommendations by January 2027.

In the meantime, lawmakers should pause the FY 2027 budget cuts until they receive the advisory council’s recommendations. The advisory council can document the harm of Alliance changes and evaluate, for example, the benefit of the District requiring Alliance beneficiaries who use FQHCs to fill their prescriptions there. FQHCs are able to purchase medications at a discount: an inhaler that costs more than $500 at a retail pharmacy is less than $30 at an FQHC.[54] Long-acting insulin is more than $100 at a retail pharmacy and less than $50 at an FQHC.[55]

DC Council Should Urge the Mayor and Chief Financial Officer to Implement Benefit Restoration

In her FY 2026 budget, Mayor Bowser proposed cutting durable medical equipment, such as inhalers, glucose monitors, and blood pressure cuffs as eligible services under Alliance. The Council Committee on Health restored this coverage for both adults and young people during the budget process. The Council-approved FY 2026 budget, however, limited the Alliance benefit package to no longer cover vision, dental, non-emergency transportation, podiatry, and home health care services unless there was adequate revenue growth to reverse these cuts.

Specifically, the Council added a provision in the FY 2026 budget that directed a portion of FY 2025 revenue growth to restore the benefit package for FY 2026 as long as the additional revenues exceed actual expenditures, as estimated by the Chief Financial Officer (CFO).[56] In December, the CFO certified the additional revenue was available, but it is not clear when benefits will be restored.[57] The Council should urge immediate implementation so enrollees can get the care they need.

The Council Should Work to Reverse Harmful Cuts to Behavioral Health Services

The Alliance has never covered outpatient mental health services, but individuals with severe mental illness were able to receive assessments, outpatient therapy, medication, or specialty in-home services through the Department of Behavioral Health (DBH). Despite the Council Committee on Health committing to working with the DHCF and DBH to maintain these services until the Alliance sunsets for adults completely, the District took these services away from residents who now surpass the income eligibility limit.[58],[59] We hope the Council can reverse these cuts, especially as they were not discussed during budget season when the Council could have acted.

- “Important Health Care Alliance Updates!,” Department of Health Care Finance, Accessed on December 6, 2025. Note that the Alliance has a 5 percent income disregard, meaning this income is not counted towards the Alliance’s income limit. These figures include the disregard.

- Department of Health Care Finance, “DHCF Responses to Committee on Health Data Requests,” November 24, 2025.

- Glen Lee, “Fiscal Impact Statement – Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Support Act of 2025,” Office of the Chief Financial Officer, July 28, 2025.

- Akeiisa Coleman, Carson Richards, Sara R. Collins, and Faith Leonard, “What Recent Policy Changes Mean for Immigrant Health Coverage,” The Commonwealth Fund, October 15, 2025.

- Laura Barrón-Lopez, Doug Adams, Ian Couzens, and Leila Jackson, “Migrants in U.S. legally and with no criminal history caught up in Trump crackdown,” PBS News Hour, March 28, 2025.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Capitation and Pre-payment,” Revised September 10, 2024.

- HealthCare.gov, “Fee for service,” Accessed November 24, 2025.

- DC Action, “Immigrant Children’s Program and DC Health Care Alliance,” February 6, 2021.

- Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025, page 68.

- Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025.

- For more information on the move away from the DC One Card, see: Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025. Note: This committee report does not list the final permissible forms of identification.

- Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025.

- Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025, page 69.

- Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025.

- DC Department of Health Care Finance. “FY 20-21 Oversight Questions Attachments.” Accessed on November 24, 2025, page 161. Note: 23.8% reported their race ethnicity to be “Other.”

- DC Department of Health Care Finance. “FY 20-21 Oversight Questions Attachments.” Accessed on November 24, 2025, page 161. Note: 23.8% reported their race ethnicity to be “Other.”

- Elissa Minoff, Isabella Camacho-Craft, Valery Martinez, and Indivar Dutta-Gupta. “The Lasting Legacy of Exclusion: How the Law that Brought Us Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Excluded Immigrant Families & Institutionalized Racism in Our Social Support System.” Center for the Study of Social Policy and the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. August 2021.

- Claire Heyison and Shelby Gonzales, “States Are Providing Affordable Health Coverage to People Barred From Certain Health Programs Due to Immigration Status,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised February 1, 2024.

- Elissa Minoff, Isabella Camacho-Craft, Valery Martinez, and Indivar Dutta-Gupta. “The Lasting Legacy of Exclusion: How the Law that Brought Us Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Excluded Immigrant Families & Institutionalized Racism in Our Social Support System.” Center for the Study of Social Policy and the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. August 2021.

- Elissa Minoff, Isabella Camacho-Craft, Valery Martinez, and Indivar Dutta-Gupta. “The Lasting Legacy of Exclusion: How the Law that Brought Us Temporary Assistance for Needy Families Excluded Immigrant Families & Institutionalized Racism in Our Social Support System.” Center for the Study of Social Policy and the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. August 2021.

- Claire Heyison and Shelby Gonzales, “States Are Providing Affordable Health Coverage to People Barred From Certain Health Programs Due to Immigration Status,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised February 1, 2024.

- Claire Heyison and Shelby Gonzales, “States Are Providing Affordable Health Coverage to People Barred From Certain Health Programs Due to Immigration Status,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised February 1, 2024.

- Claire Heyison and Shelby Gonzales, “States Are Providing Affordable Health Coverage to People Barred From Certain Health Programs Due to Immigration Status,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised February 1, 2024.“A Record of Historic Harm in the First Year of Trump’s Second Term,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 14, 2026.

- Drishti Pillai and Samantha Artiga, “Employment Among Immigrants and Implications for Health and Health Care,” KFF, June 12, 2023.

- Drishti Pillai and Samantha Artiga, “Employment Among Immigrants and Implications for Health and Health Care,” KFF, June 12, 2023.

- “Immigrants are a Vital Part of DC’s Future,” Immigration Research Initiative, Economic Policy Institute and DCFPI, April 2, 2025.

- Transamerica Institute, “Federally Qualified Health Centers,” Accessed November 24, 2025.

- Transamerica Institute, “Federally Qualified Health Centers,” Accessed November 24, 2025

- Transamerica Institute, “Federally Qualified Health Centers,” Accessed November 24, 2025.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services “Fact Sheet: Federally Qualified Health Center,” April 2009

- Ruth Pollard, “DC Health Care Finance Budget Oversight Hearing Testimony for DC Health Benefits Exchange Authority,” District of Columbia Primary Care Association, June 9, 2025.

- Akeiisa Coleman, Carson Richards, Sara R. Collins, and Faith Leonard, “What Recent Policy Changes Mean for Immigrant Health Coverage,” The Commonwealth Fund, October 15, 2025.

- Jennifer Tolbert, Sammy Cervantes, Clea Bell, and Anthony Damico, “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population,” KFF, December 18, 2024

- Patient Advocate Foundation, “Uninsured and Facing an Emergency? You’re your Rights!” Accessed November 24, 2025.

- Tzedek DC, “More than a Band-Aid: Systemic Changes to Protect DC Residents from Medical Debt,” June 2025.

- Tzedek DC, “More than a Band-Aid: Systemic Changes to Protect DC Residents from Medical Debt,” June 2025.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Reducing Unnecessary Emergency Department Visits,” Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative, Accessed on January 9, 2025.

- Johana Gonzalez-Cruz, “The Crisis of ER Wait Times in Washington: A Closer Look at Patient Impact,” Howard University Multicultural Media Academy, June 28, 2024.

- Tzedek DC, “More than a Band-Aid: Systemic Changes to Protect DC Residents from Medical Debt,” June 2025.

- Tzedek DC, “More than a Band-Aid: Systemic Changes to Protect DC Residents from Medical Debt,” June 2025.

- Tzedek DC, “More than a Band-Aid: Systemic Changes to Protect DC Residents from Medical Debt,” June 2025.

- Tzedek DC, “More than a Band-Aid: Systemic Changes to Protect DC Residents from Medical Debt,” June 2025.

- American Cancer Society, “New Study Shows Medical Debt Associated With Worse Health Status, More Premature Deaths, and Higher Mortality Rates at the County Level in the U.S.” March 4, 2024.

- Shameek Rakshit, Matthew McGough, Lynne Cotter, and Gary Claxton, “How does cost affect access to healthcare?,” KFF, April 7, 2025

- Roni Caryn Rabin, “Complications After Delivery: What Women Need to Know,” The New York Times, May 28, 2023.

- Jennifer Haley and Emily M. Johnson, “Closing Gaps in Maternal Health Coverage: Assessing the Potential of a Postpartum Medicaid/CHIP Extension,” January 29, 2021

- Wayne Turnage, Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services “Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Oversight Hearing Testimony Before the Committee on Health,” June 9, 2025.

- Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025

- Approved FY 2025 Budget and Financial Plan, July 30, 2024.

- Cynthia Cox, Jared Ortaliza, Emma Wager, and Krutika Amin, “Health Care Costs and Affordability,” KFF, October 8, 2025.

- Cynthia Cox, Jared Ortaliza, Emma Wager, and Krutika Amin, “Health Care Costs and Affordability,” KFF, October 8, 2025.

- Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025.

- Wayne Turnage, Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services “Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Oversight Hearing Testimony Before the Committee on Health,” June 9, 2025.

- Data provided to DCFPI by a District FQHC Executive Director, October 2025.

- Ibid.

- “Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Support Act of 2025,” Act 26-148, September 4, 2025.

- Glen Lee, “Certification of Additional Contingency Funding,” Office of the Chief Financial Officer, December 24, 2025.

- Committee on Health, “Report and Recommendations of the Committee on Health on the Fiscal Year 2026 Budget for Agencies Under Its Purview,” June 2025.

- Department of Behavioral Health, “Changes to Local Payments Effective October, 1 2025,” Bulletin 157, September 15, 2025.