Chairperson McDuffie, and members of the committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Caitlin Schnur, and I am the Deputy Policy Director at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI). DCFPI is a non-profit organization that shapes racially-just tax, budget, and policy decisions by centering Black and brown communities in our research and analysis, community partnerships, and advocacy efforts to advance an antiracist, equitable future.

Today, I am calling on the Council to oppose and reject Bill 25-0280 the Workers and Restaurants are Priorities Act of 2023. The Council’s efforts to support the District’s businesses, including its restaurants, are important to our economic recovery and growth. However, support to restaurants should not undermine the intent of Initiative 82 (I-82) and harm workers doing their best to get by.

Specifically, DCFPI opposes this bill because it:

- Gives special tax treatment to restaurants, which is unfair to other retail establishments and bad tax policy;

- Incentivizes and defines service charges in a way that will likely reduce tips, harming tipped wage workers and especially workers of color; and,

- Accelerates the implementation of I-82, which will likely hurt small restaurants and restaurants owned by people of color.

For these and other reasons, Council should reject this harmful bill and continue to implement I-82 as intended.

Initiative 82 and the Workers and Restaurants are Priorities Act of 2023

Last November, voters in DC overwhelmingly voted in favor of the District of Columbia Tip Credit Elimination Act of 2022, commonly known as I-82. I-82 ensures that by 2027, employers pay DC’s tipped wage workers the standard minimum wage, plus tips.[1] At the time that I-82 passed, DC’s tipped workers were paid a subminimum wage of $5.35 per hour, plus tips.[2] I-82 reset and lifted the wage floor, ensuring that all workers in the District are paid one fair wage.

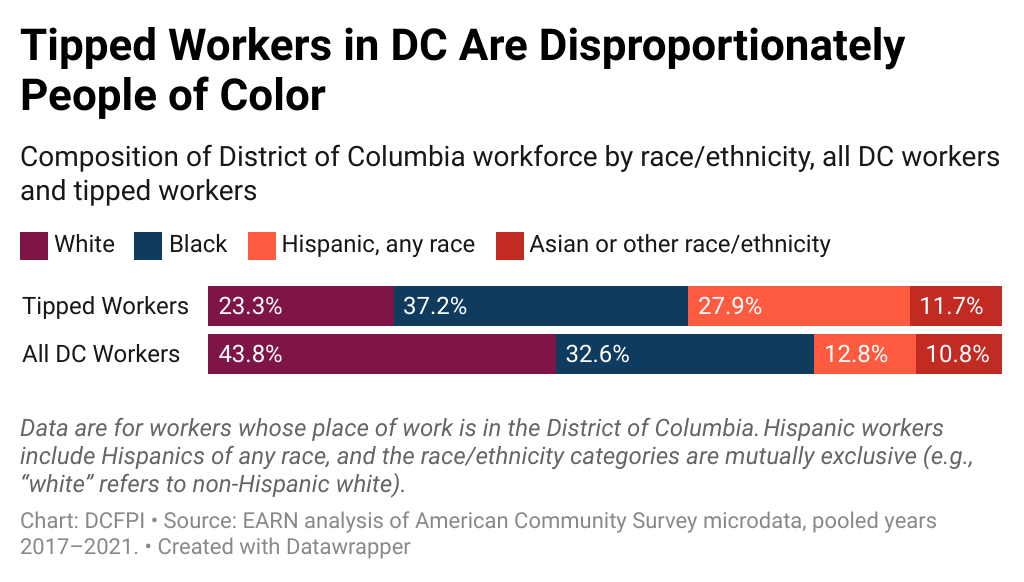

The passage of I-82 was a historic decision by DC residents to reject a business model that is built on the legacy of slavery and has disproportionately exploited and harmed people of color and women.[3] DC voters agree with the goal of I-82: to get more money into workers’ pockets, especially workers of color. Workers of color account for about 77 percent of DC’s tipped workforce (Figure 1).

The Workers and Restaurants are Priorities Act, which is supported by the restaurant lobby, undercuts I-82 by incentivizing the use of service charges to cover the cost of rising wages in a way that will likely reduce the practice of tips, thus subverting the will of DC voters to help tipped workers grow their wages.

Special Tax Treatment for Restaurants Undermines Tax and Racial Equity and Revenue Adequacy

Exempting service charges from the District’s sales tax undermines tax equity by giving special tax treatment to 1) restaurants, compared to other retail establishments, and 2) customers who are predominantly high income and likelier to be white. The sales tax exemption also undermines revenue needed to support an array of important public investments.

As discussed in greater detail below, under the proposed legislation, restaurants would be required to use service charges to pay employees’ base wages, or their labor costs. Other retail sectors, some of which also continue to struggle in this economy, cannot remove their labor costs from total sales for the purpose of a DC sales tax exemption. Lawmakers have expected these retail businesses, and other employers, to absorb higher labor costs associated with steady increases in the standard minimum wage, even as inflation and non-labor costs have grown. It is reasonable for lawmakers to set the same expectation for restaurants, which may mean the customer sees a more transparent cost for their meal upfront through menu prices.

In addition to inequity across businesses, the benefits of the bill are highly skewed by race and income. In the US, Americans who eat food outside of the home—a decent proxy for those eating at restaurants—are disproportionately higher income and white. US consumers in the top income quintile spent 4.3 times more money, on average, on food away from home than those in the bottom quintile, according to the 2021 Consumer Expenditure Survey.[4] While DC data are not available at that level of detail, this disparity is likely to be worse in the District given income inequality in DC is the worst in the nation (tied only with Puerto Rico) and average spending on food away from home was 1.5 times higher in DC than for the nation (the two-year average for DC in 2020-2021 was $4,025 compared to $2,705, nationally).[5] And because white residents are likelier to be top earners in DC, this sales tax break is likelier to benefit them than people with lower incomes, who, due to historic and ongoing racism, are likelier to be Black.[6]

Exempting service charges from the sales tax would also result in foregone revenue, the level of which remains unknown until the Office of Chief Financial Officer publishes a fiscal impact statement for this bill. However, due to the savings owners and customers would experience, this exemption would incentivize more restaurants to levy the maximum 22-percent service charge than under current law. The incentive effect would further raise the cost of the exemption. Given the fiscal constraints evident throughout the fiscal year (FY) 2024 budget process, the expiration of federal pandemic aid, and the need to continue to raise revenue to meet the Council’s pledged support to SNAP recipients and excluded workers, DC should not place unnecessary limits on its potential revenue streams.

Service Charges Will Likely Reduce Tips and Harm Workers of Color the Most

The purpose of I-82 is to get more money into workers’ pockets, not less. I-82 does this by ensuring that tipped workers receive the standard minimum wage as their base pay with tips on top. However, the widespread use of service charges that this bill incentivizes will likely cause confusion among consumers and reduce the incidence of tipping. This could lower workers’ pay and undermine the intent of I-82.

There is anecdotal evidence from the many restaurants already levying service charges that suggests restaurant consumers are unsure of whether they should tip on top of service charges. A recent Washington Post article, citing diners’ confusion, offers “guidance” on how to tip in DC, advising consumers that if a service charge goes entirely to workers, then it’s okay not to tip.[7]

Different from current law, in the proposed legislation restaurants would be required to use service charges to pay employees’ base wages. Restaurants also would have to advise consumers of service charges in advance.[8] While these provisions may be intended to benefit both workers and consumers, they are likely to have the unintended consequence of sowing confusion that results in reduced tips. For example, when a diner receives their bill and sees that it already has an additional charge of up to 22 percent that they’ve been told goes entirely to supporting worker pay, it’s reasonable to assume that many consumers will think the service charge replaces tipping and, in the words of the Washington Post, will believe it’s “okay not to tip.”

In reality, there are crucial differences between tips and service charges, as defined in this bill, that the average restaurant diner may not know. Tips legally belong to workers and service charges belong to restaurant owners. A tip supplements a workers’ base wages. As noted, this bill states that service charges must be “used to pay base wages of the employees.” By this definition, the bill language would appear to prohibit service charges from acting like a tip and supplementing base pay. This would mean that the service charge could only go to pay the prevailing minimum wage. If customers did not tip on top of the already-levied service charge, then tipped workers’ pay would stay stuck at minimum wage, which is not enough to live on in the District and also not the intention of I-82.[9]

Between 2017 and 2021, on average, the District’s servers and bartenders earned $25.53 per hour, adjusted for inflation, which is far higher than DC’s standard minimum wage. [10],[11] Put another way, if tipping becomes less common because of the widespread imposition of service charges, then this bill could reduce workers’ pay, on average, and harm restaurant workers. The District’s Black and non-Black workers of color will experience disproportionate harm from reduced tips due to service charges, given that they make up about 77 percent of DC’s tipped workforce.

Accelerated Timeline for Minimum Wage Phase-In Will Likely Hurt Small and People of Color Owned Restaurants

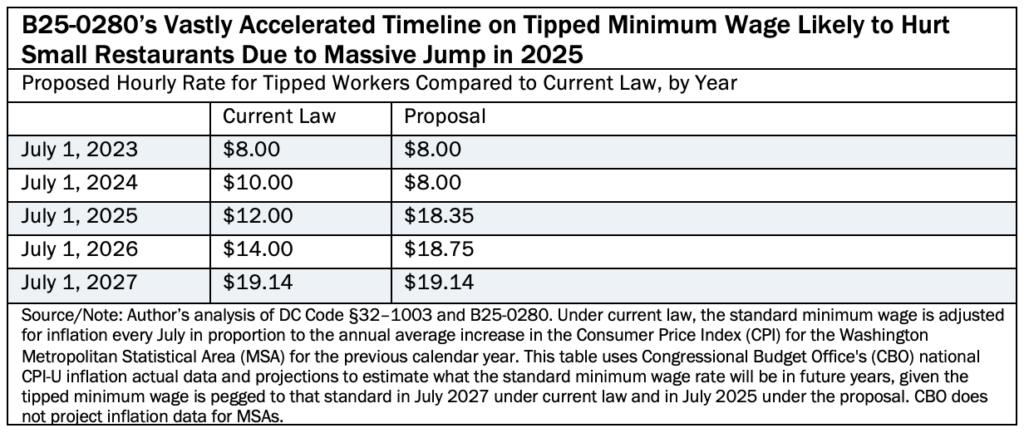

I-82 has a steady and predictable set of base wage increases for tipped workers, with base wages gradually increasing to match the standard minimum wage by 2027.[12] Gradually phasing in an increased minimum wage can help employers adapt to the new cost of labor.[13] The District undertook a gradual phase-in approach when it raised the minimum wage up to $15 per hour between July 2016 and July 2020.[14] However, the bill greatly accelerates the I-82 timeline in a way that will likely cause economic shock to small businesses.

Under current law, the tipped minimum wage is scheduled to reach $8 per hour in July 2023, followed by annual $2 per hour increases through 2026 and then it matches the standard minimum wage in July 2027.[15] The proposed bill skips the scheduled increase to $10 per hour in July 2024, keeping in place the $8 per hour wage. It then requires a massive jump to the prevailing minimum wage in July 2025—two years ahead of the I-82 schedule—which DCFPI estimates will be $18.35, or $10 per hour more than the year prior, based on projected inflation using national CPI-U data (Table 1).

Large, investor-owned restaurants in the District are better poised to adapt to this newly-accelerated timeline for increasing labor costs. However, small or family-owned restaurants, as well as restaurants owned by people of color and legacy businesses, likely have less income, accrued assets, and access to capital that they can leverage to keep up with sudden, massive spikes in labor costs.[16] As a result, small and Black-owned businesses may be hurt the most by this bill’s new wage increase timeline, causing racially inequitable harm at the same time that the mayor has called for DC to be a “leading city to start and run a business in the US, particularly for resident and Black and Hispanic owned businesses.”[17]

[1] “District of Columbia Tip Credit Elimination Act of 2022,” D.C. Act 24-700, November 30, 2022.

[2] District of Columbia Office of Tax and Revenue, “OTR Tax Notice 2023-03: Sales Tax on Additional Mandatory Charges as a Result of Initiative 82,” March 27, 2023.

[3] One Fair Wage and UC Berkeley Food Labor Research Center, “The Washington, DC

Consumers’ Guide to I-82 and Service Charges, May 2023; and, David Cooper, “Why D.C. should implement Initiative 77,” Economic Policy Institute, September 12, 2018.

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) 2021 Consumer Expenditure Survey, Table 1101, Quintiles of income before taxes: Annual expenditure means, shares, standard errors, and coefficients of variation, accessed June 2023. BLS defines food away from home as: “All meals (breakfast and brunch, lunch, dinner and snacks and nonalcoholic beverages) including tips at fast food, take-out, delivery, concession stands, buffet and cafeteria, at full-service restaurants, and at vending machines and mobile vendors.”

[5] Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2021 Consumer Expenditure Survey, Table 3024, Selected southern metropolitan statistical areas: Average annual expenditures and characteristics, Consumer Expenditure Surveys, 2020-2021; and, Bureau of Labor Statistics’ 2021 Consumer Expenditure Survey, Table 1800. Region of residence: Annual expenditure means, standard errors, and coefficients of variation, Consumer Expenditure Surveys, 2020-2021, accessed June 2023.

[6] The District of Columbia Council Office of Racial Equity and the DC Policy Center, “DC Racial Equity Profile for Economic Outcomes,” January 2021, see figure 5.

[7] Tim Carman and Justin Moyer, “How much to tip after D.C. raised the minimum wage for tipped workers,” The Washington Post, May 25, 2023.

[8] On March 7, 2023, the Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia issued a consumer alert providing information about the usage of service fees at restaurants. The consumer alert states that restaurants are allowed to charge fees, but are not allowed to hide them, obscure them in fine print, or only disclose them after a customer has already ordered. Restaurants must also inform consumers why the fees are being charged. The notice urges restaurants to prominently disclose fees at the beginning of the ordering process, accurately describe how the fee will be used, and use the fees exclusively for those disclosed purposes.

[9] As of the first quarter of 2023, the MIT Living Wage Calculation for the District of Columbia is as follows: the living wage for one adult with no children is $22.15 per hour, and the living wage for one adult with one child is $42.61 per hour.

[10] Wages are in 2022 dollars and include both base wages and tips.

[11] Economic Analysis and Research Network (EARN) analysis of American Community Survey microdata, 2017-2021 5-year sample (Ruggles et. al 2023) and Consumer Price Index data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[12] The DC government updates the standard minimum wage for inflation every July; the wage will be set at $17 per hour beginning July 2023.

[13] Jared Bernstein, “Gradual Phase-In Helps Employers Adapt to Minimum Wage Hike,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 2014.

[14] Code of the District of Columbia, “Local Business Affairs, Labor, Minimum Wages, Requirements (§ 32–1003),” accessed June 2023.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Andre M. Perry, Regina Seo, Anthony Barr, Carl Romer, and Kristen Broady, “Black-owned businesses in U.S. cities: The challenges, solutions, and opportunities for prosperity,” Brookings Institution, February 14, 2022; and, the District of Columbia Council Office of Racial Equity and the DC Policy Center, “DC Racial Equity Profile for Economic Outcomes,” January 2021.

[17] District of Columbia Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning & Economic Development, “DC’s Comeback Plan,” January 2023.