Mayor Bowser has proposed the idea of instituting a waitlist for the child care subsidy program for the first time since 2005 because DC lawmakers did not allocate sufficient funding to keep up with growing enrollment.[1] DC’s child care subsidy program helps thousands of families with low and moderate incomes pay for the cost of child care. This support is critical because DC has the highest costs for child care compared to the rest of the country, with families paying more than $23,000, on average, per year to enroll their children in infant care.[2]

Many District families simply cannot afford to pay such a high price for child care. A waitlist would put access to this critical financial support, which allows parents to work or pursue an education and ensures businesses have reliable workers, out of reach. Insufficient access to child care also harms DC’s economy because when parents cannot work, they lose earnings and spend less, which means less money flowing to DC businesses and lower tax revenue. Moreover, children need high-quality, supportive environments to develop social and emotional skills and to build foundations for future learning. Making it harder to access child care subsidies makes it more difficult for children from low- and moderate-income families to thrive. The wellbeing of District families and the future of DC’s economy will be negatively affected if lawmakers fail to increase funding for the child care subsidy program so that all eligible families can access it.

DC’s Subsidy Program Helps Make Child Care Affordable and Demand is Booming

The District’s child care subsidy program makes child care more affordable for families with low and moderate incomes. It ensures that no eligible family using a program voucher pays more than 7 percent of household income on child care, with most parents paying less than $11 per day in co-pays and many paying nothing.[3]

In 2023, DC expanded the subsidy program to families with moderate incomes—increasing income eligibility up to 300 percent of the federal poverty line, or $93,600 for a family of four—acknowledging that investing in affordable, high-quality care can facilitate economic gains for Black and brown families, small and large businesses, and the DC economy as a whole.[4]

Families are eligible to participate in the subsidy program if they meet additional requirements, such as being in an eligible education or work program or engaged in a job search.[5] There are more than 40,000 children in DC living in households that meet the income eligibility requirement, but less than 20 percent of those children utilized child care subsidies in fiscal year (FY) 2023.[6] This follows national trends: in FY 2021, only 22 percent of US children eligible under their state’s rules received a subsidy.[7] In its update to the DC Child Care Subsidy Program Policy Manual, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE) committed to improving the process to enroll in the child care subsidy program for families. Since October 2024, OSSE has:

- Put the subsidy application for parents online;

- Removed the requirement that parents work or go to school for a minimum of 20 hours per week;

- Standardized a ten-day application processing timeline for the Department of Human Services to approve or deny applications; and,

- Simplified eligibility for families receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).[8]

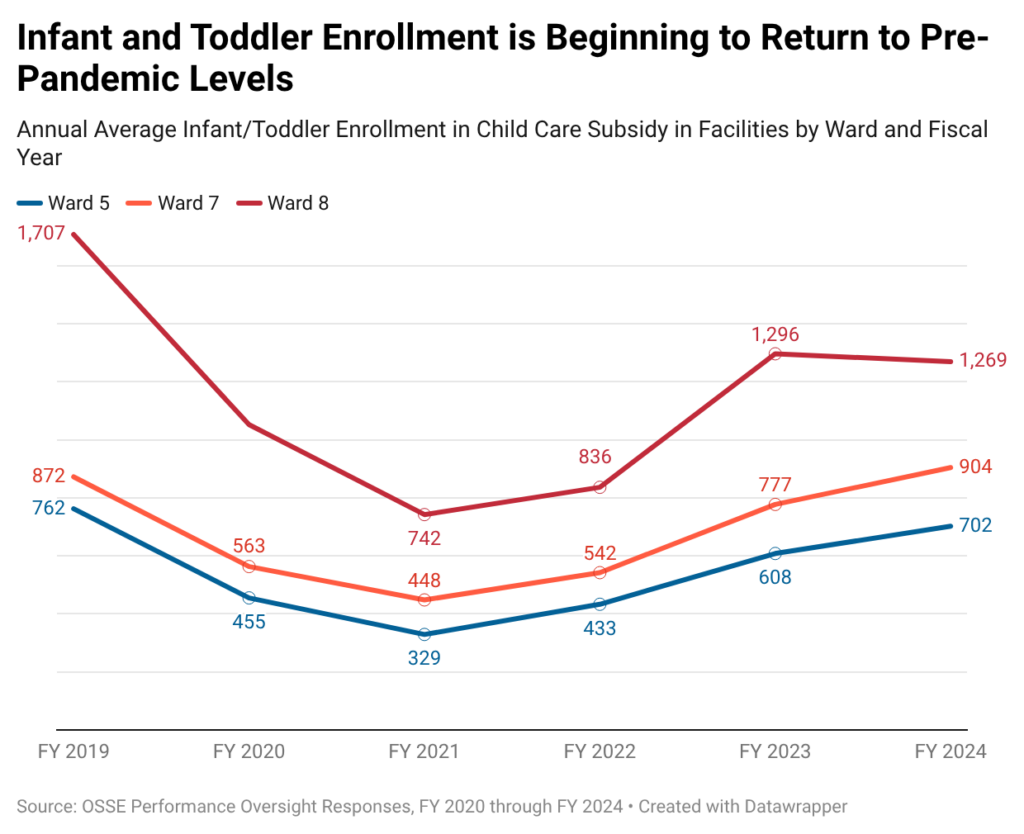

These changes appear to have increased the utilization of child care subsidies, particularly among families with infants and toddlers.[9] Child care facilities in Wards 5, 7 and 8, where Black and brown families with low incomes are concentrated, saw a decrease in infant and toddler enrollment in child care subsidy in 2020 and 2021 largely due to the effects of the pandemic, including widespread job loss that decreased the eligible population, combined with declining birth rates. Those facilities have experienced a steady increase in enrollment since then (Figure 1).[10]

Figure 1.

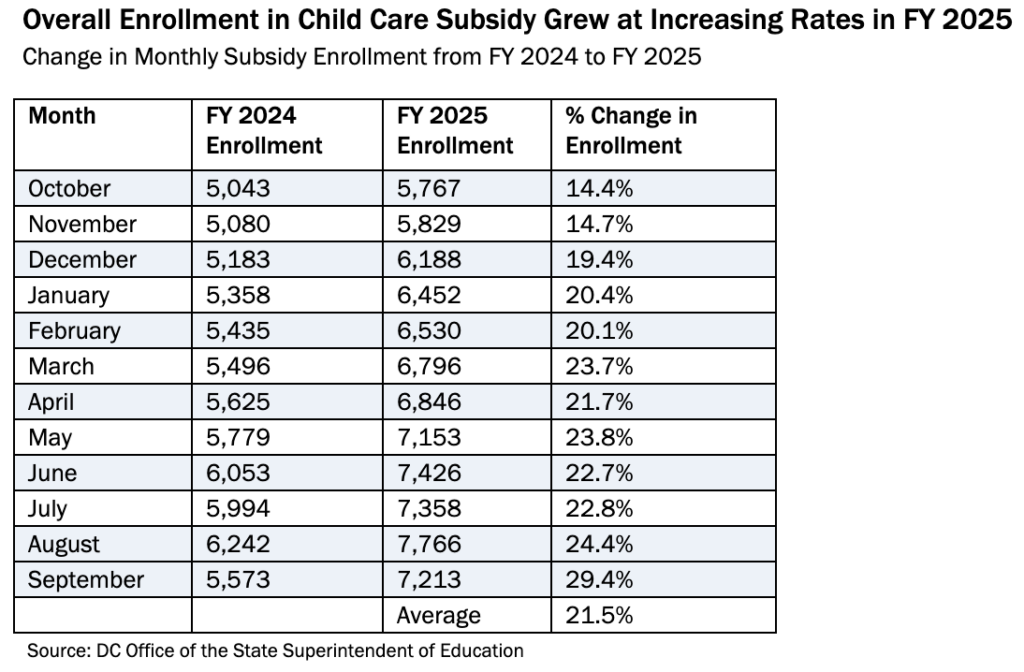

Enrollment across all eligible ages continued to increase in FY 2025, but at higher rates than in FY 2024, likely due to the changes OSSE made to make it easier for families to enroll (Table 1). Between October 2024 and September 2025, enrollment increased by approximately 1,450 children by the end of FY 2025.[11] During that same period in the previous year, enrollment grew just by 530 children and with smaller monthly increases in most cases.

TABLE 1.

Funding for the subsidy program, however, failed to keep pace with growing enrollment and fell short of meeting need. In fact, despite the upward trend, Mayor Bowser has proposed funding cuts for the program since FY 2024. The DC Council consistently identifies and allocates funding to reduce the gap but has not eliminated it.[12] Now, at the start of FY 2026, the gap between the cost of the program and approved funding for it has never been wider. OSSE spent about $127 million on subsidies in FY 2025 but DC lawmakers are only funding the program at $101.3 million for FY 2026.[13],[14] Even if enrollment were to stay flat, on net, as opposed to increasing as the data indicate it likely will, funding would still be $25.7 million short of maintaining last year’s service levels. That is equivalent to more than 1,360 subsidies based on FY 2025 average costs.[15] However, based on data from the start of FY 2026, enrollment remains above 7,000 children per month, representing a 21 to 22 percent growth rate over enrollment from that same period in FY 2025 and nearly a 40 percent growth rate when compared to FY 2024.[16] OSSE is considering instituting a waitlist due to this shortcoming and published a draft policy for the waitlist last August in anticipation of this budget shortfall, described in the textbox below.

The Child Care Subsidy Waitlist Would Put Progress at Risk and Shift Costs to Families

The improvements OSSE put in place for eligible families to more easily apply for and receive a child care subsidy appear to have significantly improved overall utilization of the program, but a waitlist threatens to undo this progress. Requiring families to wait an indefinite period of time for a child care subsidy forces families to find alternative and often less stable forms of care, like leaving their children in the care of family members or friends, or opting to stay home with their children instead of pursuing a job or educational opportunity. And, if parents know that they are unlikely to receive a subsidy in a timely manner, they may opt to not apply at all, which results in fewer families entering the program.

A reduction in the number of subsidies available to families also makes it harder to operate a child care facility that accepts subsidies. For example, Indiana lawmakers implemented a waitlist in December 2024 and reduced provider reimbursement rates to try to close a major program funding gap. As a result, providers throughout the state were forced to “lay off staff, close classrooms, reduce wages, or shut down entirely,” which reduced the availability of child care for all families, not just those who depend on subsidies.[17]

Maryland faced a similar funding crunch for its child care subsidy program at the start of 2025 and instituted a waitlist in May, with the goal of lowering enrollment in the program from 45,000 to 40,000 children to reduce costs.[18] However, enrollment has not gone down and, as of mid-September, there are more than 2,000 families on the waitlist.[19] At the same time, subsidy providers in the state have had to reduce educators’ work hours and raise tuition for parents who do not use subsidies to make up for lost funding and remain financially sound.[20]

Similarly, Virginia introduced a waitlist for its child care subsidy program in July 2024, and it remains in place today.[21] These examples provide a warning to DC that once a waitlist is in place, the savings may not be immediate and thousands of families with low incomes are left without affordable and high-quality options that better position them and their children to thrive.

With DC’s child care costs so high it rivals the cost of college tuition and financial support to offset those costs waning, DC’s families are left with impossible choices. One parent in Ward 7 said that without access to a child care subsidy, “I would be homeless; it’s either rent or day care; I would have terrible mental health,” according to a recent report by DC Action.[22] The same report highlighted other tough choices parents have to make when they cannot afford child care, like reducing work hours, declining job promotions, turning down educational opportunities, and dropping out of school entirely.[23]

These choices not only harm individual families, but DC’s entire economy. Parents forced to spend more than they can afford on child care end up spending less at other local businesses. When they cannot afford child care at all, they work less or leave the workforce altogether, which means lower income for families, less productivity for businesses, and less tax revenue for the District.[24] Instituting a waitlist for the child care subsidy program and preventing families from accessing this critical financial support harms children, families, the local child care industry, and DC’s economy—over both the short- and long-term.

DC Lawmakers Must Prioritize Child Care Funding for Economic Recovery

DC lawmakers have an opportunity to prevent harm, protect families, and boost the local economy, but only if they act quickly. They can still increase funding for the child care subsidy program for FY 2026 in the supplemental budget by allocating the contingency funding that the Chief Financial Officer approved in November, shifting funding from areas less dire for families and small business in the budget, and using any of DC’s growing revenue that may be projected in the forthcoming February revenue forecast for this fiscal year.[25] If enrollment continues to grow, lawmakers will likely need to increase funding to more than $150 million annually, up from the recurring allocation of $96 million, to eliminate the need for a waitlist. Moving forward, OSSE should begin making enrollment projections for the program so lawmakers can better anticipate costs and increase funding for the program as needed.

The end goal for lawmakers should be expanding child care subsidy access to all DC families, not just those with incomes below a certain amount. Expanding the child care subsidy program to all families would cost about $224 million annually (or $139 million more than current funding levels)—a substantial increase but with far-reaching economic benefits.[26] An investment of this size would give more than 12,500 children access to high-quality early education, create more than 3,000 new jobs across the District, add $1.4 billion to all DC workers’ paychecks, and result in $1.7 billion in economic growth in the first year alone.[27] Rather than forcing businesses and families to pay the price of insufficient funding, they could reap the economic benefits of expansion for all DC residents.

The Birth-to-Three for All DC Amendment Act of 2018 outlines an annual expansion of eligibility for the program to increasingly higher income families, but that expansion has been stalled since 2024 because lawmakers have not funded it.[28] During this time when federal policy decisions are taking resources out of the hands of those who need it most, local lawmakers must act now to strengthen the local safety net and step in to protect District families, while also strengthening DC’s economy.

- Special data request to Karen Schulman, Senior Director of State Child Care Policy, National Women’s Law Center, October 22, 2025.

- Sarah Javaid and Melissa Boteach, “Child Care is Unaffordable in Every State,” National Women’s Law Center, February 2025.

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, “DC Child Care Subsidy Program Family Fee Final Rules,” accessed November 20, 2025.

- DC lawmakers increased income eligibility to 300 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), up from 250 percent. Anne Gunderson, “Expanding Child Care Subsidies Would Boost the District’s Economy,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, July 2024.

- Children under protective services, children with disabilities, children of adults with disabilities, children experiencing homelessness, children of teen parents, children of elder caregivers, children enrolled in HS/EHS/QIN, children in families experiencing domestic violence, and children with parent participating in addiction recovery program are exempt from participating in qualifying activities. DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, DC Child Care Subsidy Program Policy Manual, pages 9-11, October 2024.

- In 2023, there were 40,295 children in the District in families with incomes below 300 percent FPL, but only 7,699 children were served by child care subsidy, based on the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities’ analysis of American Community Survey data and utilization data from the DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education.

- Nina Chien, “Estimates of Child Care Subsidy Eligibility & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2021,” Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Human Services Policy, September 2024.

- DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, “DC Child Care Subsidy Program Policy Manual,” October 2024.

- Child care subsidy can be used for children up to age 13, but DC offers universal pre-kindergarten for children ages 3 and 4 in public and charter schools, so pre-K enrollment in the subsidy program has steadily declined since FY 2019, based on data in OSSE’s annual performance oversight responses.

- Nina Chien, “Estimates of Child Care Subsidy Eligibility & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2021,” Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Office of Human Services Policy, September 2024.

- DCFPI analysis of monthly enrollment data from Andrew Gall, Deputy Chief of Staff, DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Email sent to Nora Charles, “Child Care Subsidy Requests,” October 7, 2025.

- Chairman Phil Mendelson, DC Council Committee of the Whole, “Fiscal Year 2026 Budget Report,” page 60 of 122, June 25, 2025.

- DCFPI analysis of monthly spending data from Andrew Gall, Deputy Chief of Staff, DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Email sent to Nora Charles, “Child Care Subsidy Requests,” October 7, 2025.

- Andrew Eisenlohr, Deputy Director, Office of the Budget Director, DC Council, Email sent to Anne Gunderson, “Final budget for child care subsidy program for FY26,” October 21, 2025.

- FY 2025 average cost is calculated by taking the average monthly cost and multiplying it by 12 for an average annual cost. Data for this calculation is from Andrew Gall, Deputy Chief of Staff, DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Email sent to Nora Charles, “Child Care Subsidy Requests,” October 7, 2025.

- DCFPI analysis of monthly spending data from Andrew Gall, Deputy Chief of Staff, DC Office of the State Superintendent of Education, Email sent to Nora Charles, “Child Care Subsidy Requests,” January 21, 2026.

- Rachel Wessler, “No Time to Wait: How Child Care Funding Uncertainty and the Reemergence of Waitlists are Shaping Families’ Futures,” Child Care Aware of America, November 7, 2025.

- William J. Ford, “Enrollment for child care scholarships still closed, unclear when it might reopen,” Maryland Matters, September 16, 2025.

- Ibid.

- Rachel Wessler, “No Time to Wait: How Child Care Funding Uncertainty and the Reemergence of Waitlists are Shaping Families’ Futures,” Child Care Aware of America, November 7, 2025.

- Virginia Department of Education, “Paying for Child Care,” accessed October 30, 2025.

- Audrey Kasselman, “Navigating DC’s Child Care Subsidy Program: What Families Experience and What Needs to Change,” DC Action, page 11, September 2025.

- Ibid.

- Sara Watson, “The High Cost of Unaffordable Child Care,” Under 3 DC, March 2024.

- To learn more about the Business Activity Tax, see: Nick Johnson, Tazra Mitchell, and Erica Williams, “A Business Activity Tax Would Make DC’s Tax System More Equitable While Raising Revenue,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 30, 2025.

- Anne Gunderson, “Expanding Child Care Subsidies Would Boost the District’s Economy,” DC Fiscal Policy Institute, July 17, 2024.

- Ibid.

- DC Law 22-179: Birth-to-Three for All DC Amendment Act of 2018.