DC is experiencing an affordable housing crisis with more than 82,000 residents facing unaffordable rents, poor conditions, or evictions.[1] Instead of addressing this crisis through proven solutions, such as vouchers and affordable housing preservation, the DC Council is poised to gut tenant protections by weakening the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA). TOPA allows tenants the right to buy their building when it goes up for sale or assign their purchase rights to a developer of their choice. TOPA has created or preserved more than 16,000 units of affordable housing in the past 40 years.[2] Despite a track record of creating affordability for tenants, preserving affordable housing, and ensuring residents’ negotiating power, DC leaders have limited TOPA rights multiple times over the past decade and are set to do so again.

The latest round of changes to TOPA are the most extreme yet; Mayor Bowser’s Rebalancing Expectations for Neighbors, Landlords, and Tenants Act (RENTAL Act) will leave tens of thousands of renters without TOPA protections with disproportionate harm to Black renters, especially those living in Wards 7 and 8. The current version of the bill following revisions from DC Council contains three types of exemptions from TOPA:

- Covenant exemption: Buildings where the new buyer is willing to agree to a covenant that promises 51 percent of the units will be affordable at 80 percent Area Median Income (AMI) for 20 years.

- Retroactive new construction: Buildings built between 2010 and 2025 will be retroactively exempt from TOPA. Tenants in these buildings currently have TOPA rights and would lose them with the passage of the bill until their buildings reach 15 years of age (e.g. a building constructed in 2015 would be exempt from TOPA until 2030).

- Prospective new construction: Newly constructed buildings will be exempt from TOPA until the building reaches 15 years of age (e.g. a building built in 2027 will be exempt from TOPA until 2042).

The stated goals of these changes are to encourage investment in new construction and create affordability, but the actual effect of these exemptions will be worse outcomes for tenants, less affordability in preservation deals, less agency and power for renters at the lowest income levels, and fewer building repairs.

At the second vote on the RENTAL Act, the Council should reject these exemptions. The Council is right to pursue a swift response to the affordable housing crisis, but wrong in pursuing harsh developer-driven policy changes that unnecessarily eliminate longstanding tenants’ rights and harm tens of thousands of current and future renters.

Proven and sensible alternatives have been put forward. DC Council can double down on the preservation focused solutions already under consideration and give tenants the resources they need to make the housing decisions that work best for their families and neighbors. They can also implement a narrowly tailored exemption for investors, as proposed by the Office of the Tenant Advocate, to exclude them from the TOPA process. This direction avoids discouragement of investment—a stated central goal of the legislation—and preserves TOPA rights for DC tenants.

TOPA Gives Tenants a Seat at the Table

TOPA gives a tenant association in a for-sale building the first right to purchase their building or assign their rights to a developer of their choice. Even if residents do not purchase their building, TOPA allows them to negotiate with potential purchasers and then assign their rights to a party they choose. Tenants most often use these negotiations to ensure their units remain affordable, secure needed repairs, or even ensure some newly affordable units. TOPA was originally designed to function as a right for tenants, but in past years DC leaders have exempted individual buildings, single family homes, and areas of downtown from the law, leaving tenants without critical protections. (Sources: Office of the Tenant Advocate, “TOPA Single-Family Home Reform Law Takes Effect,” July 23, 2018. Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development, “Washington DC’s Housing in Downtown Program” January 2024. “Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act of 1980,” Sept. 10, 1980, D.C. Law 3-86, § 401, 27 DCR 2975.)

RENTAL Act Fails to Create True Affordability for Renters with Middle and Low Incomes

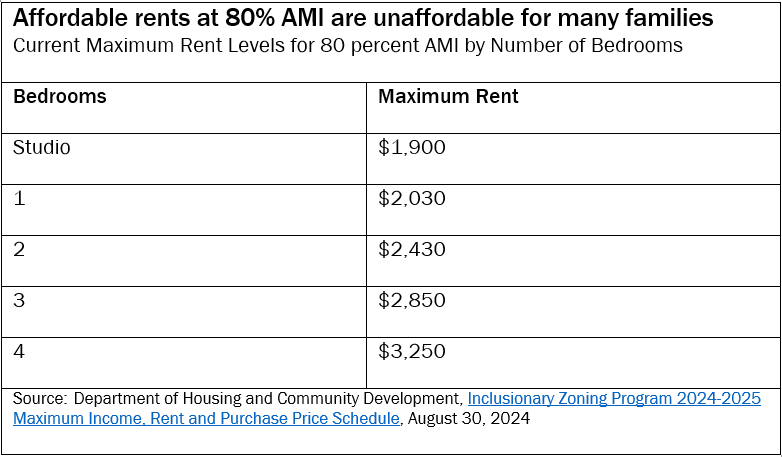

The RENTAL Act would not create truly affordable units with its covenant exemption because in many parts of the city, particularly in Wards 7 and 8, rents at 80 percent AMI are higher than market rate rents.[3] AMI is a measure of the median income in a region, which for DC, includes its wealthy suburbs. This means that the AMI used for housing programs in DC is higher than the actual income of residents in the city. In 2024, for instance, 80 percent AMI for the DC region (the AMI used for DC’s housing programs) was $100,995, but 80 percent AMI for DC alone is $87,765.[4,][5] This means that affordability tied to AMI is higher than what many residents of DC can afford. Table 1 shows the current maximum rent levels for 80 percent AMI by number of bedrooms. A three-bedroom unit affordable at 80 percent AMI would rent for $2,850 a month.

Using the small area fair market rent metric calculated by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, shows that $2,850 would be above market rent in 83 percent of the zip codes in DC.[6] So the ‘affordable units’ created by this covenant would often be more expensive for families than units on the open market in these areas. These zip codes are disproportionately located in Wards 7 and 8, and it is precisely in these areas of the District where TOPA has been used most frequently to increase affordability, negotiate better living conditions, and protect renters.[7]

The RENTAL Act Sacrifices Tenants Rights without Improving TOPA

The covenant exemption in the RENTAL Act would allow developers to avoid TOPA and ignore the concerns and struggles of renters in a building, all without creating true affordability or even agreeing to preserve existing affordability. This is particularly true for Black and brown residents or those at lower income levels who are most likely to be facing housing insecurity due to affordability.[8] In its Racial Equity Impact Assessment, the Council Office of Racial Equity found that Black renters will be disproportionately impacted by the exemptions.[9] They stated that the exemptions “will certainly reduce Black tenants’ ability to protect affordability in their homes and worsen their housing outcomes.”[10]

Any covenant or affordability exemption is a missed opportunity for a better deal through TOPA. The flexibility of the TOPA process allows for expanded affordability as well as the power of tenants to negotiate solutions that might otherwise be missed such as repairs, additional family units, or quality of life improvements. According to The Coalition’s TOPA study, 78 percent of units involved in TOPA transactions received repairs or renovations. Exempting properties from TOPA will pre-empt opportunities for these kinds of negotiated improvements. While recent statements by the mayor and Councilmember Robert White have implied that the sole purpose of TOPA is to preserve affordability, this misses the full intent of TOPA. As stated by Rick Eisen, one of the drafters of the original legislation, TOPA was originally intended to give tenants bargaining power when large scale changes were coming to their buildings.[11] Tenants should have a seat at the table, to create affordability, but also to push for unit repairs, common area fixes, and other quality of life issues.

The RENTAL Act Complicates the TOPA Timeline Potentially Costing Tenants a Chance to Exercise Their Rights

The covenant exemption introduces confusion into the TOPA process and this confusion could cost tenants an opportunity to exercise their TOPA rights. Currently, when a property owner decides to sell a building, they send the tenants an offer of sale notice. In most cases, the building owner already has a prospective buyer and has negotiated a contract setting the price of the building and the terms of the sale. This offer of sale kickstarts the TOPA process, wherein the tenants have 45 days (in buildings with five or more apartments) to organize a tenants association and decide if they are interested in using their TOPA rights. (If there is an existing tenant organization, they have 30 days to express interest). The covenant exemption proposed in the RENTAL Act would allow a prospective buyers who indicates that they will pursue a covenant to bypass TOPA altogether. Tenants would receive a notice of transfer that would indicate that the exemption was triggered and that they do not have TOPA rights regarding the sale of the building. As flawed as the covenant exemption parameters are, this part of the process is fairly clear.

However, if a prospective buyer cannot find funding to make a covenant financially viable, the process reverts back to the tenants. This means that tenants, having just received notice that they do not have TOPA rights, would then be notified that the prospective buyer cannot pursue a covenant, and that they do now have TOPA rights. This would be an incredibly confusing process and one that would make it more difficult for tenants to organize if they believe their building to be exempt from TOPA.

New Construction Exemptions are an Unnecessary Blunt Instrument that Will Leave Tenants in Newer Buildings Without TOPA Protections

The new construction exemptions in the RENTAL Act will take away TOPA rights from tens of thousands of current and future tenants. This would represent a historic loss of tenants’ rights in the District. The retroactive new building exemption would impact an estimated 81,156 units in buildings constructed since 2011.[12] It is difficult to calculate the number of units impacted by the prospective new construction exemption, but every resident of a new building moving forward from the passage of the bill would not have TOPA rights for 15 years.

These exemptions aim to increase new construction in DC by allowing investors to take their money out of newly constructed buildings without triggering TOPA. The entity that develops and constructs a building is rarely financially able to cover the cost of a new building directly. They seek out investors, who may include private entities or public funds for affordable units. These investors become a part of the ownership of a new building. Under current TOPA laws, these investors, who usually do not plan to be involved in the operation of a building, may trigger TOPA when divesting from the building’s ownership after it is fully leased. To prevent this issue, the RENTAL Act would deny TOPA rights to every renter in a newly constructed building until 15 years after issuance of a “permanent, new” certificate of occupancy. It seeks to allow these investors to recoup their investment and exit ownership with the hope that these investors would use the capital from exiting building ownership to invest in other new housing construction.

While building new housing is a critical part of reducing rents, the loss of TOPA rights in all new buildings for 15 years is too high a cost. It has been suggested that TOPA is rarely used in new buildings but this justification ignores the fact that 76 percent of buildings built in DC were constructed before 1978, so use of TOPA naturally skews towards older buildings. Newer buildings also tend to have more units, so the exemption of these buildings will impact a larger number of tenants per building.[13] And as explained below, this is an unnecessary gutting of DC’s longstanding tenant rights when a much better, more narrowly targeted alternative has been put forward by the Office of the Tenant Advocate.

The Council Can Create Affordability and Spur New Investment Without Gutting Tenants’ Rights

While the RENTAL Act is an ineffective and harmful tool, its stated goals for investment in new housing and creating affordability are crucial to improving housing outcomes for DC tenants. Luckily, the District has effective tools to preserve affordable housing and local officials have proposed less harmful alternatives to drive new residential construction

Increased Funding for Housing Preservation Can Provide Affordability for DC Tenants and Strengthen TOPA

Rather than targeting TOPA with exemptions, the Council should support the tools that make TOPA effective. Ongoing, consistent funding for preservation does this and is the most effective way to create and preserve affordable units. The District’s preservation programs, including the Housing Production Trust Fund (HPTF) and First Right to Purchase Program (FRPP) are existing tools for preserving and creating affordable units. With consistent preservation funding, tenants going through the TOPA process could work with developers to create affordability, while providing the repairs, additions, and expanded affordability that comes when tenants are treated as experts in the needs of their buildings.

Council has already started to focus on this type of funding in the fiscal year (FY) 2026 budget, which set aside $20 million for housing preservation within the HPTF with the potential to rise to $30 million if there is revenue growth later in the year. However, this is not enough. The set-aside is a one-time allocation of funding. By creating a permanent set aside, the Council can ensure predictable funding for developers seeking to preserve affordable housing.

The Council could also fund the FRPP—a fund dedicated to TOPA deals—with dedicated funding that is available throughout the year. HPTF funds are available only at designated times when the Department of Housing and Community Development releases the consolidated Request for Proposals. FRPP would be available on an ongoing basis, helping tenants who cannot predict when their landlord might decide to sell their building.

A Narrow Exemption for Investors Can Spur Investment in New Buildings While Preserving Tenants Rights

To spur invest in new construction, the Office of the Tenant Advocate has proposed language that would allow investors to enter or exit ownership without triggering TOPA, so long as they are not the primary operator of the building. Entities that only provide funding and do not operate the buildings could provide investment for new construction and preservation deals and, once the most of the units are rented out, those investors could take their money out without engaging in the TOPA process. This solution offers greater flexibility to investors as they could enter or exit ownership of the building at any point in the building life cycle (as opposed to just the initial 15 years).

The RENTAL Act sacrifices tenants’ rights and power under the auspices of generating new development. By pursuing alternate strategies, DC could avoid repeating harms of its past where such sacrifices have lead to displacement, particularly of Black residents.[14] By supporting and investing in preservation, strengthening TOPA, and pursuing more narrow and flexible exemptions, DC Council can achieve its goals of new development without leaving tenants behind.

[1] Solari, Claudia, “Housing Insecurity in the District of Columbia.” Urban Institute. November 16, 2023.

[2] The Coalition, “Sustaining Affordability: The Role of Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) in Washington, DC,” November 15, 2023.

[3] Zielinski, Connor and Mychal Cohen, “Nearly Half of All Renters and More Than Half of Black Renters in DC Struggle to Afford Rent” DC Fiscal Policy Institute. April 14, 2025.

[4] Department of Housing and Community Development, Inclusionary Zoning Program 2024-2025 Maximum Income, Rent and Purchase Price Schedule, August 30, 2024

[5] US Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2024 1-year Data.

[6] US Department of Housing and Urban Development, “FY2025 Small Area FMRs.” Accessed August 27, 2025.

[7] The Coalition, “Sustaining Affordability: The Role of Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) in Washington, DC,” November 15, 2023.

[8] Solari, Claudia, “Housing Insecurity in the District of Columbia.” Urban Institute. November 16, 2023.

[9] Council Office of Racial Equity “Racial Equity Impact Assessment: Rebalancing Expectations For Neighbors, Tenants, And Landlords (Rental) Act Of 2025.” July 14, 2025.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Meima, Judy, “Lessons from 20 Years of Enabling Tenants to Buy Their Buildings.” Shelterforce. November 23, 2020.

[12] Washington DC Economic Partnership, “Development Report 2024/25.” Accessed August 27, 2025.

[13] Council Office of Racial Equity “Racial Equity Impact Assessment: Rebalancing Expectations For Neighbors, Tenants, And Landlords (Rental) Act Of 2025.” July 14, 2025.

[14] Gwam, Peace and Mychal Cohen, “Combating the Legacy of Segregation in the Nation’s Capital.” Accessed September 3, 2025.