This research was done in partnership with the Immigration Research Initiative.

DC prides itself as a welcoming city—one that values and respects immigrants and recognizes their immense contributions to our economy, communities, and culture. More than 95,000 immigrants (14 percent of the local population) call DC home.[1]

The Trump Administration is undertaking an unprecedented intensity of enforcement actions to remove immigrants from their communities, from their workplace, and often from their families. The administration is promising to radically reduce the number of new immigrants allowed into the country and has stripped some documented immigrants of their legal status or work authorization.[2]

This brief details the economic risks to DC of increased immigration enforcement and mass deportations, including:

- Potential risks to critical sectors with a large percentage of immigrant workers, such as child care, health care, and hospitality;

- Job losses for non-immigrant DC workers in industries that depend on immigrant workers, such as construction and restaurants; and,

- A loss in local tax revenue paid by immigrants who are undocumented that could be as much as $73.6 million, at a time when DC is experiencing tight budgets.[3]

The toll of the administration’s actions cannot only be considered in economic terms. Fear of deportation is harming the lives of immigrants in DC. As discussed in this brief, many immigrants are afraid to go to work, are keeping their children home from school, are not accessing medical care, or are staying home from religious and community events.

Both Undocumented Immigrants and Those with Legal Status are at Risk for Deportation

Of the more than 95,000 immigrants who live in DC, nearly 47,000 people were non-citizens in 2023.[4] An estimated 25,000 immigrants in DC were undocumented.[5] The other non-citizen immigrants have a range of legal immigration statuses, including legal permanent residents (green card holders), Temporary Protected Status (TPS) recipients, student visa holders, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, asylum seekers, and H1-B visa holders (for highly-skilled workers).

The immigrants most vulnerable to deportation are those who are undocumented, but the harm does not end there. The administration has also targeted many groups with legal immigration status for deportation. The administration has acted to de-document 350,000 people from Venezuela who had TPS, an action that has so far not been stopped by the Supreme Court, and has launched similar proceedings for people with TPS from Haiti, Afghanistan, Cameroon, Nepal, Honduras, and Nicaragua.[6],[7] The administration has targeted student visa holders and legal permanent residents for deportation, based on political speech and activities.[8] The fear stoked by these actions affect immigrants who have legal status or are citizens, especially those who live in mixed-immigration status households, where some family members are citizens or have other legal immigration status while others are undocumented.

Mass Deportations Would Shrink DC’s Labor Force and Increase Costs

In 2023, 16 percent of DC workers were immigrants, including both documented and undocumented immigrants.[9] If a large number of workers were to be deported, it is unlikely that a sufficient number of US-born workers could replace all of them, especially in industries heavily reliant on undocumented immigrants like hospitality and construction.[10] This large loss of workers would cause a labor supply shortage and force businesses to shrink. Labor shortages would also lead to higher prices, increasing the cost of living for DC residents who will pay more for groceries, restaurants, construction, child care, home health care, and more.[11]

Child Care, Health Care, Hospitality, and Other Critical Industries are At Risk from Mass Deportations

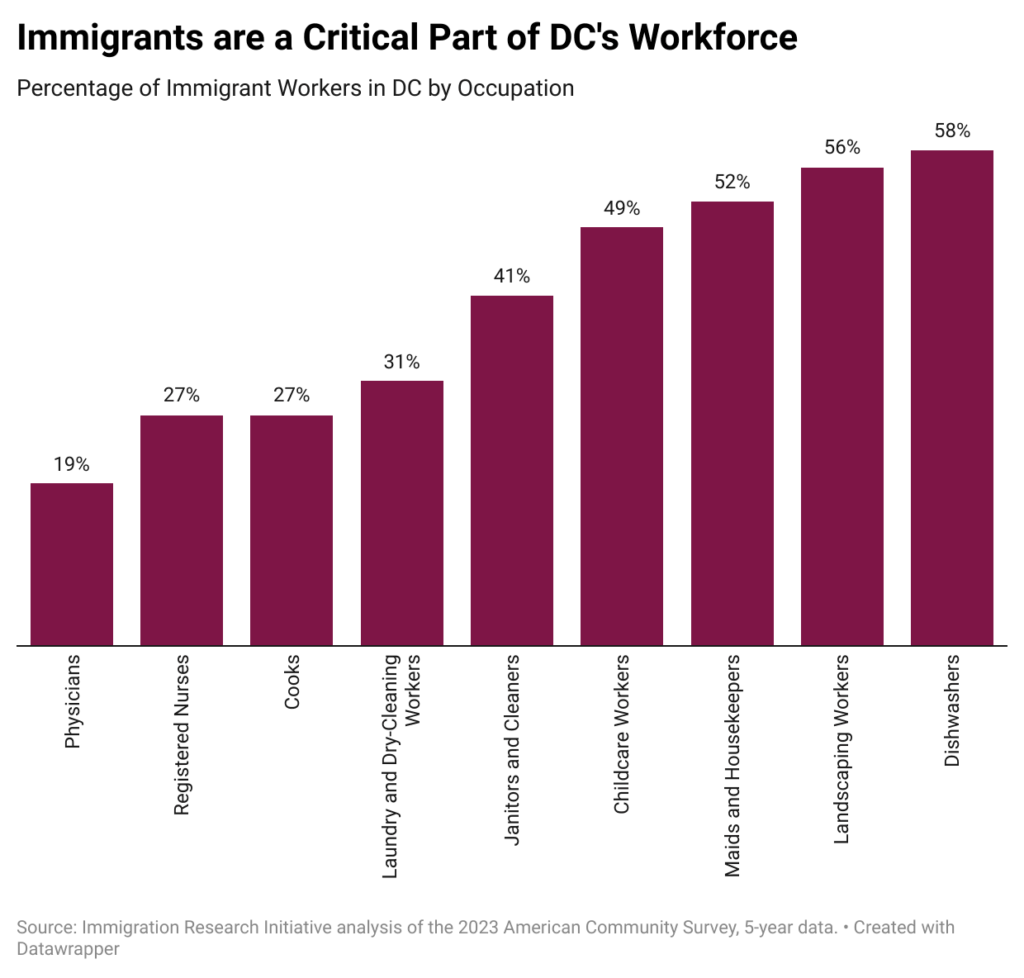

Immigrants in DC help support a vibrant mix of jobs and sectors. They play an essential role in caring for the health of DC residents, building homes and schools, caring for our children, keeping our homes and offices clean, and much more. As shown in the graph, the occupations in DC that have a large percentage of immigrant workers—both documented and undocumented—include landscaping workers (56 percent), maids and housekeepers (52 percent), child care workers (49 percent), janitors and cleaners (41 percent), cooks (27 percent), and registered nurses (27 percent).[12]

We do not know how many of the immigrant workers in these occupations in DC are undocumented and therefore at the highest risk for deportation. However, we know that nationally, many of these occupations have a significant percentage of undocumented workers. An estimate from the Pew Research Center shows that 12 percent of cooks, 11 percent of janitors, and 24 percent of maids and housekeepers nationally are undocumented.[13]

Mass Deportations Pose Broad Risks for DC’s Economy

Mass deportations would affect economic output, tax revenues, and business activities in DC. Immigrant workers, both documented and undocumented, accounted for 15 percent of the economic output in DC in 2023.[14] Undocumented immigrants contribute $73.6 million in local taxes, which help pay for the vital programs and services that DC residents rely on.[15] Furthermore, 21 percent of business owners in DC in 2023 were immigrants, providing a vital economic engine.[16] These local businesses help maintain the vibrancy of DC’s economy by spurring innovation, hiring workers, and adding locally owned storefront shops that keep DC’s neighborhoods vibrant.

The deportation of immigrants would also result in a predictable decline in the number of jobs for US-born workers.[17] Rather than replacing US-born workers, the types of jobs filled by undocumented immigrants, such as construction workers or cooks and dishwashers, complement the types of jobs US-born workers are hired for, such as construction site managers or restaurant servers. If construction companies experience a shortage of construction workers, for example, they cannot take on as many projects, reducing jobs for construction managers. Undocumented immigrants also work in jobs that are essential to others’ participation in the workforce, such as providing child care for working parents. Finally, without spending on goods and services by undocumented immigrants, local businesses would not need as many workers.[18] All of this adds up to a decrease in work for US-born workers.

Fear of Deportation is Impeding Immigrants’ Participation in Economic and Community Activities

Intensive US Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) enforcement, breaking with long-standing ICE guidance about targeting sensitive locations like schools, religious institutions, and hospitals, threats to immigrants with legal status, and hyper-charged political rhetoric is all combining to create a climate of fear for immigrants.[19] In DC, these threats took on more intensity after President Trump announced a takeover of the Metropolitan Police Department on August 11, and the Justice Department is seeking to compel local police to cooperate with immigration enforcement.[20] Since August 11, ICE has greatly increased enforcement activity in DC, including the violent arrest of a delivery driver.[21] This comes after months of ICE activity in the DC area that already heightened District immigrants’ concerns. For example, ICE agents tried to detain a health care worker on school grounds at HD Cooke Elementary School in March.[22] In May, ICE agents went to many DC restaurants demanding that owners show work eligibility documents for their employees.[23]

The current climate of fear is having a broader chilling effect beyond those targeted or at increased risk for deportation, including on immigrants with temporary or provisional work permits and even some who hold green cards or are naturalized citizens. Past research has found that during periods of increased immigration enforcement, even immigrants not targeted for deportation were afraid to leave their homes to participate in everyday activities.[24]

Fear is particularly acute for the many immigrants in mixed status families in which some family members are undocumented and others are US citizens or have another legal immigration status. A survey conducted in December 2024 as people were preparing for the new administration found that 60 percent of respondents in mixed-status families worried about participating in one or more of seven everyday activities, such as going to work, visiting a doctor or hospital, sending children to school, or attending religious services or community events, because they do not want to draw attention to their immigration status or that of a family member.[25]

Many immigrants of all statuses are deciding to stay home as much as possible to avoid interactions with immigration authorities. A survey of over 2,000 Spanish-speaking immigrants conducted in March 2025 found that 2 in 5 respondents had to miss work because of the federal government’s new immigration agenda.[26] As these surveys show, many immigrants are pulling back from economic activities like working or shopping in their local community, avoiding community events, and not engaging in activities vital to their health and mental well-being—all of which harm the immigrants themselves, hurt DC’s economy, and dampen the District’s cultural and community life.[27]

Immigrants Help Keep DC Economically Strong and Culturally Vibrant

Mass deportation would harm DC’s economy, thwart business activity, and take a devastating toll on immigrant families and communities. DC’s lawmakers should uphold the current policy of non-cooperation and take any additional policy actions within their purview to protect all of DC’s residents, communities, and economy.[28] DC is stronger when we embrace our diverse backgrounds and experiences and unite around inclusive policies that keep our communities strong and grow jobs and wages for everyone.

- Immigration Research Initiative analysis of the 2023 American Community Survey. Note that this document includes both one-year and five-year data from the American Community Survey because of data availability. One-year and five-year estimates should not be compared with each other.

- Tara Watson and Jonathan Zars, “100 days of immigration under the second Trump administration,” Brookings Institution, April 29, 2025.

- Carl Davis, Marco Guzman, and Emma Sifre, “Tax Payments by Undocumented Immigrants,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, July 30, 2024.

- Immigration Research Initiative analysis of the 2023 American Community Survey, one-year data.

- The number of immigrants who are undocumented is estimated by the Pew Research Center based on the 2022 American Community Survey. For more information, see 50 States: Immigrants by Number and Share.

- Dara Lind, “Supreme Court ‘De-Documents’ 350,000 Venezuelans – And Keeps Everyone In The Dark About What’s Next,” American Immigration Council, May 21, 2025.

- Robert Tait, “Trump Ends Deportation Protection for People from Honduras and Nicaragua,” The Guardian, July 7, 2025.

- Watson and Zars, 2025.

- 2023 American Community Survey, five-year data.

- American Immigration Council, “Mass Deportation: Devastating Costs to America, Its Budget and Economy,” October 2024.

- Cristobal Ramon and Gabrielle Berger, “The Economic Costs of Mass Deportations of Long-Time Residents,” UnidosUS, December 6, 2024.

- All state-level data about immigrant occupations is from Immigration Research Initiative analysis of the 2023 American Community Survey five-year data.

- National estimates of the number of undocumented workers were provided to IRI by Jeff Passel of the Pew Research Center, and are based on an analysis of the 2022 American Community Survey, consistent with the analysis in “What We Know About Unauthorized Immigrants in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, July 22, 2024.

- Immigrant share of economic output is estimated by showing the share of all earned income – wages plus proprietors’ earnings. The data source is the 2023 American Community Survey, five-year data.

- Davis, et al, 2024.

- 2023 American Community Survey, five-year data.

- Chloe East, et al, “The Labor Market Effects of Immigration Enforcement,” Journal of Labor Economics, Vol. 41, No. 4, October 2023. This work is summarized in an accessible fashion by Chloe East in, “The Labor Market Impact of Deportations,” The Hamilton Project, September 18, 2024.

- Chloe East, “The Labor Market Impact of Deportations,” The Hamilton Project, September 18, 2024.

- For an overview of immigration policies and actions in the first 100 days of the Trump administration, see Watson and Zars, 2025.

- Meagan Flynn, Jenny Gathright, and Jonathan Edwards, “Immigration enforcement shaped first week of Trump’s D.C. takeover,” The Washington Post, August 18, 2025.

- Dan Rosenzweig-Ziff, Katie Mettler, Teo Armus, and Emma Uber, “Federal officers detain, tackle moped driver amid Trump D.C. police crackdown,” The Washington Post, August 17, 2025.

- Lauren Lumpkin and Hau Chu, “Federal agents attempted to detain worker at D.C. school, officials say,” The Washington Post, March 26, 2025.

- Tim Carman, Warren Rojas, and María Luisa Paúl, “Widespread ICE visits leave D.C. restaurant owners, workers rattled,” The Washington Post, May 7, 2025.

- East 2024.

- Hamutal Bernstein, Dulce Gonzalez, and Diana Guelespe, “Immigrant Families Express Worry as They Prepare for Policy Changes,” The Urban Institute, March 12, 2025.

- Anthony Capote, David Dyssegaard Kallick, Cyierra Roldan, and Shamier Settle, “Responding with Courage: How Spanish-Speaking Immigrants Report Being Impacted by the New Deportation Regime”, The Immigration Research Initiative, May 8. 2025.

- For more on the how deportation fears harm immigrants, see: Kristina Fullerton Rico, “Deportation fears create ripple effects for immigrants and their communities,” The Conversation, February 19, 2025.

- D.C. Act 23-207. Sanctuary Values Congressional Review Emergency Amendment Act of 2020.