Chairman Mendelson and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. My name is Kate Coventry and I am a senior policy analyst at the DC Fiscal Policy Institute. DCFPI is a nonprofit organization that promotes budget choices to reduce economic and racial inequality and build widespread prosperity in the District of Columbia through independent research and thoughtful policy recommendations.

I am here today to testify on how the Council should increase investments in permanent housing, Project Reconnect, the Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP), public housing repairs, and excluded workers.

The Mayor’s Budget Invests in Permanent Housing, but Much More is Needed

Housing is healthcare. Every day individuals experiencing homelessness die from preventable and manageable diseases. Now during the pandemic, the connection between housing and healthcare is even more evident when one of the keys to staying healthy is staying at home. This is particularly true for residents who are chronically homeless, meaning they have been homeless for years and suffer from life-threatening health conditions and/or severe mental illness.

DCFPI envisions a future where no one is chronically homeless and no one dies without the dignity of a home. The fiscal year (FY) 2022 budget is a tool to make this vision a reality but only if the Council makes bold investments that build upon what is included in the Mayor’s proposed budget.

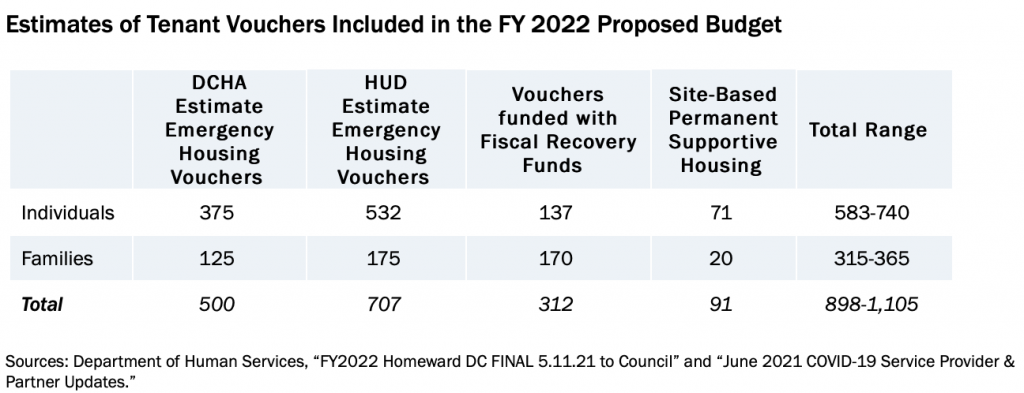

The proposed budget combines $11.7 million of Emergency Housing Vouchers (EHV) funding in the American Rescue Plan (ARP) and Fiscal Recovery Funds to create new Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH) slots for individuals and families that are homeless. While the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimates this will translate into 707 vouchers, the DC Housing Authority (DCHA) estimates that it will create just 500 vouchers because of DC’s high rents. DCHA has asked HUD for additional funding to increase the number of vouchers. The following chart outlines the potential scenarios.

While this is a significant investment in individual PSH, it meets just 21 to 27 percent of the 2,761 slots needed. And very troubling, the investment does not exceed what was funded in FY 2020, the year in which DC dedicated the most resources ever for individuals (138 site-based units and 615 vouchers, for a total of 753 slots that year). The Council should invest $55.2 to $59.5 million more to meet the full need for individuals.

The family PSH investment meets 73 to 84 percent of the need of 432 slots and falls far short of the 464 vouchers and 20 site-based units funded in FY 2019, the year in which DC dedicated the most resources ever for families experiencing homelessness. The Council should invest $2.8 to $4.9 million to meet the full need for families.

There is no new funding for Targeted Affordable Housing (TAH), which combines a tenant voucher with light touch services. We requested 928 new slots and none were funded. The Council should invest $23.34 million to meet this need for families.

The Mayor’s Budget Does Not Invest in Local Rent Supplement Program Tenant Vouchers

DC’s Local Rent Supplement Program (LRSP) provides rental assistance to help cover the difference between rent that families with low-incomes can pay and the rent they face. One component of LRSP operates by providing vouchers to households to help them afford private-market apartments, known as “tenant-based vouchers.” Over 39,000 DC households are on DCHA’s waiting list for this program.[1] Demand for housing assistance is high, with nearly 60 percent of the District’s lowest income households—those earning less than $20,000 annually—being severely cost burdened, meaning they spend more than 50 percent of their income on rent.[2]

The pandemic has exacerbated the need for housing assistance, as an average of 39,000 DC adult renters reported that their household was behind on rent between April 28th and May 24th 2021, according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. This is likely still an underestimate as non-response to the survey is higher among groups that are younger, have lower levels of education, and identify as Black or Latino—all groups that are more likely to struggle to pay rent.

Yet, once again, the mayor didn’t propose an increased investment in tenant-based vouchers to help households pay the rent, so it will fall on the Council to provide new assistance for families on DCHA’s waiting list. Our partners and DCFPI recommend that the Council invest $17.3 million to provide tenant vouchers to 800 households on the DCHA waiting list in FY 2022.

The Mayor’s Budget Underfunds Project Reconnect; the Council Should Double It

The proposed FY 2022 budget for Project Reconnect is $325,000 lower than last year. Project Reconnect helps individuals who are newly homeless find alternatives to shelter such as reuniting with friends and families. Shelter can be traumatic and unsafe; avoiding shelter can benefit individuals.[3] Additionally because of budget limitations, only about 1 in 10 homeless individuals in DC receive housing assistance in any given year, which means that shared housing may be the best option for an individual. Given that the end of the eviction moratorium will likely lead to an increase in the number of people experiencing homelessness or on the verge of homelessness, the Council should invest $1.375 million in this program, doubling the budget and the number of individuals who can be served.

The Mayor’s Budget Invests Fewer Local Dollars in the Emergency Rental Assistance Program Relative to Last Year; the Council Should Level Fund It

The proposed Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) local fund budget is $8.5 million. The FY 2021 budget was $14 million and included $5.5 million in one-time funds. The proposed budget did not replace this one-time funding. ERAP helps residents facing eviction pay for overdue rent and related legal costs. The program also provides security deposits and first month’s rent for residents moving into new homes. DHS reports that they believe the $352 million in federal eviction prevention funding in the STAY DC (Stronger Together by Assisting You) program will reach most of those in in need, reducing the need for ERAP. DCFPI and other advocates worry that not all residents will qualify for STAY DC, such as those who have rental arrears from more than a year ago or those who need more than 18 months of total assistance. DCFPI urges the Council to add at least $5.5 million to bring funding up to the FY 2021 level and increase funding now to meet any need for eviction prevention or security deposits that will not be met by STAY DC.

The Mayor’s Budget Makes Modest Investments on Youth Homelessness, the Council Should Do More

Many youths experience homelessness without their parents or guardians and do not have children of their own. These “unaccompanied” homeless youth fall into two broad categories: those under age 18 and those who are 18 to 24 years old. In DC, youth under age 18 can only access housing and shelter dedicated to this population. Older youth, often called transition-aged youth (TAY), can access both TAY programs and adult housing and shelter.

The proposed budget modestly invests in youth homelessness, with just $53,920 for a pilot project consisting of 10 PSH slots for youth aging out of the adult system. Youth with high needs who age out of the youth system and become homeless again must compete with highly vulnerable adults, who are older and have more severe medical needs for limited PSH slots. This pilot will allow the youth system to explore how to best transition high need young people from the youth system into the adult system.

The proposed budget dedicates $1.3 million in one-time funding to keep 50 shelter beds for transition aged youth (TAY), youth aged 18 to 24, open through FY 2022, thus maintaining last year’s level. The budget also includes 1.5 million in Fiscal Recovery Funds to right size the budget for Extended Transitional Housing.

The budget unwisely removes $307,000 from various youth homelessness line items to fund the Rise Program, a new trauma therapy program for youth up to age 24. While advocates and providers agree this service is needed, it should not be funded by reducing existing homelessness programs. The Council should restore this funding.

The budget lacks funding for several key investments and the Council should fund the following:

- $75,000 in one-time funds for a cost analysis on the true costs of providing youth programs. Funding levels across youth programs vary greatly depending on the provider. This creates inconsistency in the quality and depth of services provided. An external cost analysis will help DHS and service providers create an ideal program model and budget accordingly;

- $574,000 in workforce programming for homeless youth. In FY 2021, the Department of Employment Services (DOES) cut this amount from their year-round youth employment program. By restoring this cut with local funds and specifically targeting these resources to homeless youth, the District can increase the number of homeless youth earning living wage jobs they need to afford housing;

- $70,000 for professional development so agencies can hire youth who have experienced homelessness. Many youth who have experienced homelessness would like to work in the field to help others who are experiencing homelessness but most providers lack funding for training. This investment would pay for a series of year-long trainings that prospective staff at any provider could attend;

- $558,000 to create a mobile behavioral health team that can meet youth where they are. Timely access to prescriptions and regular participation in therapy can be challenging for homeless youth who often lack funds for transportation and must wait for months for appointments. A mobile behavioral unit can visit youth sites to ensure easier and regular access; and

- $350,000 for a mentoring program pilot for 70 homeless youth. This is a request from youth experiencing homelessness. Access to mentors and supportive adults is critical to long-term success, but homeless youth face unique barriers to cultivating these kinds of connections.

Mayor’s Investment in Public Housing Falls Short, the Council Should Allocate $60 Million

Due to federal underfunding, the overwhelming majority of public housing units in DC are in need of significant repairs, and many residents live in deplorable conditions.[4] The COVID-19 virus is particularly deadly to those with already compromised immune or respiratory systems.[5] It is unconscionable to allow public housing residents to live in poor conditions at any time but particularly during a pandemic when these conditions can increase their likelihood of death as a result of this devastating virus.[6] Over 90 percent of residents living in the District’s public housing are Black, making this yet another issue of racial inequality. Failure to deeply invest in necessary rehabilitation of public housing units is a failure to address a deeply racialized public health crisis.

In recent years, the District has directly committed local funding to support public housing repairs, including $19 million in FY 2018, $3.25 million in FY 2019, $24.5 million in FY 2020, and $50 million in FY 2021 for a total of $97 million.[7] Yet DCHA, which owns and manages public housing, has reported that its immediate repair needs over the next six years are much higher—$405 million—while long-term repairs will require close to $2.5 billion.

This year, the mayor’s proposed budget allocates $22 million in FY 2022 for public housing repairs and maintenance in the capital budget and an additional $35 million in the following two years of the financial plan. But in the recently released errata letter, the Executive has confirmed that just three buildings of the more than 80 percent of DCHA buildings that need urgent repairs in this city. Over a year ago, the DCHA Director reiterated in the transformation plan that, “significant portions of DCHA’s public housing portfolio have deteriorated to such a condition as to be potentially uninhabitable, or threatening to the health and safety of our residents.”[8] This plan to only spend repair money on three projects directly goes against the urgent call that the DCHA Director, residents, and advocates have consistently made before this committee for funding to address ongoing repair needs at many properties.

Even with the change in leadership, these dire repair needs will not go away. We need $60 million in FY 2022 for repairs at multiple properties so that we do not stall progress nor lead to the privatization of more properties over time. Last year, the final budget stipulated that DCHA must submit a proposed spending plan to the Council and to the Council chairpersons with oversight of DCHA.[9] The Council can use this process this year to ensure DCHA has a plan in place to spend the $60 million allocation during the search for a new permanent Director.

Mayor’s Budget Makes Small Investment in Excluded Workers, Council Should Invest More

In this pivotal moment, DC policymakers must spend federal rescue funds in a timely way, with a laser focus on addressing the racial inequities that have excluded Black and brown communities from economic gains and left them more vulnerable to the COVID-19 crisis. Within DC’s hardest hit industry of leisure and hospitality, employment is still down by 48 percent or nearly 40,000 jobs, and occupational segregation within that industry has exposed Black and brown workers to the worst job losses.[10], [11] These workers, many of whom are excluded from federal assistance, faced elevated levels of unemployment and lacked high-paying job opportunities before the pandemic due to a long history of structural racism, discrimination, and economic exploitation.[12]

It will take intentional investments and interventions to reverse course and pursue an equitable future for these workers. But unfortunately, federal policymakers excluded certain residents—including those who are undocumented, returning citizens, or otherwise in the informal cash economy like domestic workers, day laborers, sex workers, and street vendors—from federal relief efforts that provide vital cash assistance to help with bills and basic needs. The District stepped up and approved cash grants to help them pay for basic needs, totaling $5 million in FY 2020 for undocumented workers and $9 million in FY 2021 for excluded workers.[13] Still, the total funding of $14 million for excluded workers—a one-time payment of $1,000 per person—is not enough to meet ongoing needs during this prolonged crisis.

A coalition of DC’s excluded workers have called upon the DC Council to provide a total investment of $200 million in cash assistance for them to support their ability to pay for basic needs such as medicine, transportation, diapers, childcare, and debt that they have incurred throughout this pandemic. This investment would provide each qualified excluded worker with $12,000 (equivalent to $1,000 per month for the first year of the pandemic), which is still substantially less than the roughly $42,000 maximum that unemployed workers who were eligible for federal assistance received over the past year.

This direct call is supported by research, which has shown that having flexible cash assistance is crucial to provide stability for individuals and children, reduce stress, and avert extreme hardship.[14] And new research from the Economic Security Project, in the context of guaranteed income programs, demonstrates that unrestricted cash is care for Black women and mothers. Cash enables them to provide safety, security, and choice for themselves and their families.

This $200 million investment would also provide support for program outreach and administration. Through outreach, we would be able to make sure we reach 1,900 new excluded workers and provide technical assistance for recipients to learn how cash (either as a large lump sum or recurring payments) could affect their other benefits, if they receive any.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury encourages states to use the Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds of the American Rescue Plan to address economic harm caused by the public health emergency, including economic harms to workers and households, and to serve the hardest-hit communities and families.[15] The District should follow the lead of other states—such as Washington, Oregon, and Colorado—that have used federal or a combination of federal and local dollars to fund cash assistance for excluded workers.[16] Additionally, New York recently was the first state to provide cash assistance to undocumented workers that is on rough par with unemployment insurance—with each worker in the first tier of eligibility receiving $15,600.[17] DC should learn from these state models and leverage the one-time federal relief dollars to fulfill the demand of $200 million in cash assistance from our excluded worker community.

Thank you for the chance to testify, and I’m happy to answer any questions.

[1] Data provided by the DC Housing Authority to DCFPI.

[2] Michael Bailey, Eric LaRose, and Jenny Schuetz, What will it cost to save Washington, D.C.’s renters from COVID-19 eviction?, Brookings Institution, July 23, 2020.

[3] “Diversion,” National Alliance to End Homelessness, August 10, 2010, https://endhomelessness.org/resource/diversionexplainer/

[4] Morgan Baskin, As D.C. Weighs How to Fix Its Public Housing, Families Keep Getting Sicker, Washington City Paper, March 20, 2019.

[5] Mayo Clinic Staff, COVID-19: Who’s at higher risk of serious symptoms?, Mayo Clinic, May 18, 2021.

[6] Mitch Ryals, Against Advice of Attorneys and Internal Auditors, DCHA Kept Families in Units With Lead Past Legal Deadline, Washington City Paper, February 26, 2021.

[7] DC Fiscal Policy Institute, Fiscal Year Budget Toolkits, Fiscal Year 2018 – Fiscal Year 2021.

[8] DC Housing Authority, DCHA Transformation Plan, September 17, 2019.

[9] Doni Crawford and Eliana Golding, What’s in the FY 2021 Approved Budget for Affordable Housing? , DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 14, 2020.

[10] Economic Policy Institute analysis of data from Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Employment Statistics, April 2021

[11] Elise Gould and Melat Kassa, Low-wage, low-hours workers were hit hardest in the COVID-19 recession: The State of Working America 2020 employment report, Economic Policy Institute, May 20, 2021.

[12] Doni Crawford and Kamolika Das, Black Workers Matter: How the District’s History of Exploitation & Discrimination Continues to Harm Black Workers, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, January 28, 2020.

[13] Kate Coventry, Qubilah Huddleston, and Alyssa Noth, What’s In the Approved FY 2021 Budget for the Safety Net?, DC Fiscal Policy Institute, September 21, 2020.

[14] Tazra Mitchell, TANF at 22: Cash Income Is Vital to Families Living on the Edge, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, August 20, 2018.

[15] U.S. Department of Treasury, Fact Sheet: The Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds Will Deliver $350 Billion for State, Local, Territorial, and Tribal Governments to Respond to the COVID-19 Emergency and Bring Back Jobs, May 10, 2021.

[16] Nina Shapiro, Washington Legislature approves $340M for COVID-19 Immigrant Relief Fund, making it one of the country’s largest, The Seattle Times, April 29, 2021.

[17] David Dyssegaard Kallick, Brief Look: Excluded Worker Fund: Aid to Undocumented Workers, Economic Boost Across New York State, Fiscal Policy Institute, April 7, 2021.