In recent years, there has been increasing attention to the District of Columbia’s high debt levels, which are among the highest per capita when compared with other cities and states. DC’s debt consumes nearly 12 percent of the operating budget, more than the 10 percent recommended by bond rating agencies.

In response, the DC Chief Financial Officer, Dr. Gandhi, has recommended that the District set a goal of having debt payments equal 10 percent of our budget or less, with an actual cap equal to 12 percent. [1] The District currently operates under a cap of 17 percent, which is widely recognized as too high. Setting a lower cap is needed, Dr. Gandhi says, to help the District maintain and improve its bond ratings.

Over the summer, legislation was introduced in the DC Council to set a 12 percent cap on debt. The legislation is sponsored by 11 of the 13 DC Councilmembers – a sign of strong support for the idea of a debt cap – but the legislation also has raised several questions about what a debt cap should look like: whether the debt cap should be tied only to general obligation debt or whether it should also include debt issued for economic development, like TIF, where taxes generated by the completed project are used to pay off the debt; whether the cap should be set at 12 percent of expenditures or at a higher level; and whether setting a cap would affect the District’s ability to fund economic development, especially in neighborhoods.

This analysis addresses these issues and comes to three broad conclusions:

- Setting a debt cap at 12 percent and including all debt supported by DC taxes is important to managing the city’s finances. Bond rating agencies understand that debt creates long-term obligations for states and cities, and they examine the totality of a jurisdiction’s debt – including debt for economic development projects that generate new tax revenues – when setting bond ratings. Many other states have debt caps for this reason, and the caps often are below 10 percent. In Maryland, for example, debt payments cannot total more than 8 percent of revenue, and in Virginia the limit is 5 percent.

- A 12 percent debt cap in DC would allow economic development efforts to continue. Setting a cap at 12 percent – which is above the level recommended by bond rating agencies – would allow the District to maintain its capital budget at current levels and to move forward with all planned economic development projects. It also would allow the city to support notable amounts of new development projects in the future. There is no doubt, however, that a debt cap would require the District to make choices with regards to new debt, just as every aspect of our budget requires setting priorities and living within limits.

- A debt cap will help the city prioritize its capital budget and economic development needs. Whether or not DC adopts a legislated cap, the CFO will warn against any projects that would push DC’s debt payments above 12 percent of expenditures. Monitoring our debt to remain within a specified cap would lead the city to develop a process for setting priorities for projects that involve debt – both public infrastructure projects and economic development subsidies for commercial projects. The worst thing to happen would be to pursue new capital projects and economic development projects without a plan – and then one day find that an important project cannot be funded because issuing more debt would risk our bond rating. It is far better to plan now to make sure we fund priority projects while staying within the debt limits recommended by bond rating agencies.

Setting a 12 Percent Debt Cap Is an Important Fiscal Management Tool for DC

Many cities and states use a debt cap as a fiscal management tool. Managing debt is important because it is a key factor that bond rating agencies use when setting a jurisdiction’s bond rating. High debt ratios can lead to lower bond ratings, which in turn result in higher interest rates and interest payments on bonds. Low debt ratios on the other hand, can help maintain or improve bond ratings, resulting in substantial interest savings.

Rating agencies focus on debt levels because debt creates a long-term claim on a state or city’s future resources. When DC issues bonds, for example, it pledges revenue for 20 years or more to repay the debt. Bonds must be repaid even when the economy weakens and tax collections shrink. For these reasons, limiting the share of a city or state’s resources tied to debt repayment makes sense. A cap on debt helps ensure a balance between funds needed to operate current programs and services and funds for investment in infrastructure or economic development.

Moving about 10 percent (debt service as a share of expenditures) is generally a “red flag” in the eyes of bond rating agencies, according to Dr. Gandhi.[2] If debt is above this level, there is a greater risk that a jurisdiction may have difficulty repaying. That is why many states have debt caps and plans to manage debt. In Maryland for example, the state has a cap that debt service cannot exceed 8 percent of revenues.[3]

In considering a debt cap for the District of Columbia, two broad guidelines emerge: a debt cap should be set as close to 10 percent of expenditures as possible, and the cap should include all debt supported by DC taxes, including TIF and other debt issued for economic development projects.

Setting a Cap at 12 Percent or Lower of Expenditures

Some policymakers have questioned whether 12 percent of expenditures is the right target for DC’s debt cap and have suggested setting a cap at a higher level, such as 13 percent or 14 percent. Yet as noted, bond rating agencies consider a jurisdiction’s debt level to be reasonable if debt payments equal no more than 10 percent of the budget. This suggests that it is important to maintain debt as close to the 10 percent level as possible. Creating a debt cap equal to 13 percent or 14 percent of expenditures may not be low enough to maintain as strong a bond rating as possible.

Including All Tax-Supported Debt under the Cap

DC’s current 17 percent debt cap applies only to general obligation debt, which are bonds issued for public infrastructure projects. The cap does not include debt issue for economic development projects in which the funds borrowed to subsidize a commercial development are paid off with taxes created by the completed project. The largest such programs in DC, TIF and PILOT subsidies, use property and sales taxes (in case of TIF) generated from the completed projects are dedicated to re-paying the bonds issued for the project.

While some policymakers have raised the question of why this kind of “self-supporting” debt should be limited at all, there are in fact a number of compelling reasons to include economic development debt in DC’s debt cap.

- Bond rating agencies consider all tax-supported debt when making bond-rating decisions. All tax-supported debt, including economic development debt, represents a long-term claim on future tax revenue. The logic for managing the amount of debt a city or state has – i.e., not tying up too much of the jurisdiction’s future revenue stream – suggests that all debt should be included in any debt management plan. Just as an economic decline may make it hard to pay off general obligation debt, it also would make it hard to pay off economic development debt.

- Economic development debt can consume a large amount of future tax revenues. When debt is issued to subsidize new commercial development, it means that the future tax revenues from that project will be tied up repaying the subsidy and will not be available as general revenues. While it makes sense to subsidize projects that will generate new tax revenues, there is also logic to limiting the amount of future revenues devoted to such projects. If the District were to subsidize a large share of new business development this way, much of the city’s future tax base would be diverted from the general fund and would not be available to fund ongoing programs and services.

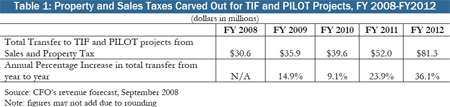

This can be illustrated using DC’s current economic development debt as an example. In FY 2008, some $31 million in DC property and sales tax revenues were used to pay off TIF and PILOT debts. This figure will nearly triple by FY 2012, to $81 million.

- Excluding economic development debt from a cap could limit DC investments in public infrastructure. Because bond rating agencies look at overall debt when setting bond ratings, an increase in economic development debt would reduce the amount of debt that could be issued for infrastructure investments using general obligation bonds. If economic development debt is not included in DC’s debt cap, it increases the chance that general obligation debt could be limited at some point. It is important to include all tax-supported debt under one cap, so that the District can plan for a balance of public infrastructure debt and economic development debt.

- Placing no limit on economic development debt gives it an advantage over other worthy projects that are not directly self-supporting. Improving roads, building new libraries, repairing schools are all good for the quality of life and are likely to promote economic development by encouraging people to move to or remain in the District. If such projects are subject to a debt cap while economic development subsidies are not, however, this would put important public works projects at a relative disadvantage to economic development projects.

A 12 Percent Cap Would Not Put a Halt to Development

Some Councilmembers have expressed a concern that managing our debt with a 12 percent cap would affect the ability to support economic development projects, especially neighborhood development. Yet a 12 percent cap would allow DC to fund all existing economic development projects and those in the pipeline. It also would allow the city to maintain current levels of general obligation bonds for capital projects, and it would leave some left over for new economic development projects.

In fact, Dr. Ghandi’s recommendation of a 12 percent cap is intended to allow the city to continue existing and planned projects. The CFO’s recent debt letter mentions that the District should ideally keep its debt payments capped at 10 percent of the budget. Since the District already has a number of approved projects in the pipeline that would place our debt payments above that level, however, a 10 percent cap would require the city to scale back its capital plans or economic development projects, or both. The 12 percent cap represents a compromise that can allow the District to fund important economic development projects while maintaining its strong financial status.

To be sure, just as the District must make choices in operating and capital budgets, a debt cap will require the city to make some choices and set priorities in the future, but not by jeopardizing economic development. A 12 percent cap would include all of the following:

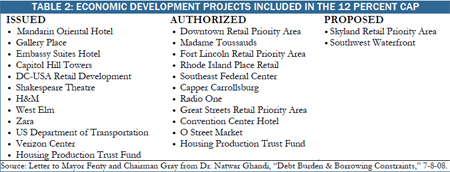

- All approved economic development projects as well as projects in the pipeline: Table 2 lists all of the issued and authorized economic development projects already included under the cap. And two projects in the planning stages, Skyland and SW Waterfront have been factored in as well.

- Funding for Neighborhood Development: The economic development projects listed above also include funding for neighborhood development. Included is $95 million in TIF funds for DC’s Great Streets program. This program works to revitalize neighborhood commercial corridors in just about every ward in the District.[4] Planned projects also include $200 million for New Communities projects that would come from issuing bonds backed by the Housing Production Trust Fund.

- Annual funding for on-going capital improvements, including schools modernization: The cap also includes $400 million in annual general obligation debt for on-going capital improvement projects. The includes important infrastructure projects such as school modernization funding, and funds for the already approved Government Centers, East Washington Traffic Initiative and Consolidated Laboratory Facility Projects. Additionally, funds for DC’s master equipment lease/purchase program are included in the proposed cap. Beyond FY 2013, the CFO estimates that borrowing for on-going general infrastructure debt and economic development debt could grow by 4 percent per year and remain in the debt cap.[5]

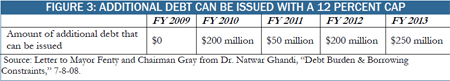

- Funding for future development: Beyond all of the projects listed, the CFO has also identified additional amounts of debt that could be issued going forward, either for general obligation debt or other types of debt such as for economic development projects. According to the CFO the following total amounts of debt could be approved in each fiscal year:

It’s important to note that even though the cap would not allow other new debt to be issued in FY 2009, it does not mean that projects cannot be discussed or moved forward in FY 2009. It simply means that any bond issuances for projects cannot begin until FY 2010 and after. Given the amount of time that it takes to plan and begin economic development projects, and the fact that DC typically does not issue these bonds until construction begins, it is unlikely that any new project approved in FY 2009 would be ready to have debt issued before FY 2010.

There are Many Sources of Funding for Neighborhood Development Projects

One of the concerns raised by policymakers is that a debt cap would affect neighborhood development. Yet as noted above, a 12 percent debt cap would support numerous existing neighborhood development projects and would allow the city to pursue additional projects in the future. In short, a debt cap would not mean that neighborhood development would have to come to a halt.

While the cap will cause the District to prioritize future projects, it is important to note that neighborhood development can be accomplished with a number of already approved and ongoing projects and programs, some of which include already approved debt and some of which are made through direct appropriation in the operating budget. These include:

- The Great Streets initiative: as mentioned previously, this project includes $95 million to develop neighborhood corridors in almost all wards.[6]

- The Neighborhood Investment Fund: authorizes up to $10 million to be spent annually to fund neighborhood development projects in 12 selected areas in the city.

- reSTORE DC and DC Main Streets: both programs work to help businesses and commercial developments in targeted neighborhoods improve their business through a variety of means.

- Affordable housing developments: developments can be made in neighborhoods through a variety of programs within the Department of Housing and Community Development including: Low Income Housing Tax Credit’s, Multi-Family Housing Rehabilitation Loans, New Construction and Site Development assistance, and Housing Production Trust Fund monies.

Beyond these programs, smaller neighborhood projects could be accommodated in the operating budget. Some $100 million of school construction is funded that way each year, for example.

The Debt Cap Can Help the District Plan and Prioritize Development and Infrastructure Projects

A debt cap would serve as an important first step in establishing a debt management process to help the District think strategically about how, and what, the District will fund with its debt capacity. With or without a cap, the CFO will still urge the District to keep all of its tax-supported debt below 12 percent. Without a plan for monitoring and managing debt, the District could find itself in the unfortunate circumstance of one day finding out that it cannot issue more debt for a worthwhile project without hurting the bond rating. It is important to take a holistic approach to manage debt in order to ensure that priority projects can be funded within our debt capacity.

A plan for managing debt would not only help the District balance its resources between neighborhood development, economic development and public infrastructure projects, having a debt management plan also is looked upon favorably by bond rating agencies and is an important factor they look at when assessing ratings.[7] This could lead to lower interest rates, which could save millions of dollars in annual interest payments.

Other jurisdictions use various mechanisms for creating and updating a debt management plan. Some of these mechanisms include:

- A debt affordability analysis: Many jurisdictions issue an annual debt affordability analysis, which often examines current debt and how much debt a jurisdiction can afford to take on in a given time period. The report examines all debt included under a jurisdictions debt cap. Since debt service on any given project can often go for 20 years or more, the analysis presents the debt picture for an extended period of time. This is similar to the debt letter Dr. Ghandi has issued recently on an annual basis.

If this District were to adopt a similar debt affordability analysis to the ones used in other jurisdictions, it should also include an assessment of both general obligation debt needs and economic development debt needs. Because debt creates long-term financial obligations, such an analysis also should make long-term projections (such as 10 years or 20 years) of expected debt needs and the impact on the city’s finances.

Along with a debt affordability analysis, the CFO could also issue a “˜debt cap impact’ analysis along with the fiscal impact statement (FIS) for each proposed project to show what impact a project would have on the cap.

- An advisory board or commission: Some states also utilize a commission or committee of stakeholders, and the public, to review debt capacity, debt affordability, and to help plan for future debt uses.

In Maryland, the state charges the Capital Debt Affordability Committee (CDAC), with issuing an annual report that reviews the size and condition of current debt issuances and advises the state on the amount of new debt that may be issued in the upcoming fiscal year.[8] The CDAC also reviews affordability criteria and other resources that may be available to support debt service. Virginia has a similar advisory committee.[9] Both Maryland and Virginia’s committee’s include key government stakeholders as well as members of the public.

In Austin, Texas the city created the Citizen’s Bond Advisory Committee (CBAC), which consisted solely of members of the public, to select and prioritize projects for an upcoming bond referendum. The CBAC developed and used a framework to evaluate projects that included criteria such as: sustainability, integration into existing/developing projects, urgency, fiscal responsibility, and public support, to name a few.[10] After the success of the referendum the city dissolved the CBAC and created a new Bond Oversight Committee, also consisting solely of public members, to monitor and report on the projects passed under the referendum.

The District can use the debt cap as a catalyst to begin creating a debt management plan to evaluate and coordinate future development. The debt management plan should include a mechanism for examining current debt and future debt affordability. The plan should also allow for a process where the public and officials can weigh in on goals, priorities and criteria for public infrastructure, neighborhood, and economic development projects. This, along with a debt cap, would help ensure the District is investing its limited resources in priority projects for DC residents.

[1] Letter to Mayor Fenty and Chairman Gray from Dr. Natwar Ghandi, “Debt Burden & Borrowing Constraints,” 7-8-08.

[2] Letter to Mayor Fenty and Chairman Gray from Dr. Natwar Ghandi, “Debt Burden & Borrowing Constraints: Background and Analysis,” 7-8-08.

[3] “Report of the Capital Debt Affordability Committee on Recommended Debt Authorizations for FY 2009,” Capital Debt Affordability Committee, October 2007, available at: http://www.treasurer.state.md.us/reports/2007-CDAC-Report.pdf (last accessed: October, 6, 2008)

[4] Ward 3 does not have any Great Street corridors included in this project.

[5] Letter to Mayor Fenty and Chairman Gray from Dr. Natwar Ghandi, “Debt Burden & Borrowing Constraints,” 7-8-08.

[6] Ward 3 does not have any Great Street corridors included in this project.

[7] New York City Independent Budget Office, “How Much is Too Much? Debt Affordability Measures for the City,” Fiscal Brief: April 2006, available at: http://www.ibo.nyc.ny.us/

[8] “Report of the Capital Debt Affordability Committee on Recommended Debt Authorizations for FY 2009,” Capital Debt Affordability Committee, October 2007, available at: http://www.treasurer.state.md.us/reports/2007-CDAC-Report.pdf (last accessed: October, 6, 2008)

[9] The Debt Capacity Advisory Committee was created to review and analyze the state’s debt. Information available at: http://www.trs.virginia.gov/Debt/dcac.asp

[10] Douglas, Jennifer R., “Best Practices in Debt Management” Government Finance Review, April 2000, available at: http://www.gfoa.org/